Hello everyone, welcome back! I’m taking a short mid-year break at the moment so no devlog update this week, but I want to instead share some thoughts and reflections I’ve been having on some of the earliest experiences I had with procedural content generation techniques, even if at the time of course I had no idea what to call these. This is something I’ve been thinking about for quite a while, and now that I look back I can see aspects in each of the games I’m going to look at here, as well as in my reactions to these games, which have really influenced and will continue to influence URR’s design and my overall philosophies in terms of using randomization techniques to create interesting gameplay. As such, I wanted here to take a look at three older games – One Must Fall 2097, Freelancer, and Neopets – which each did interesting PCG things that had a real effect on me when I played them, and that (now I look back and reflect with a more mature and critical eye) do actually suggest some pretty interesting discussions and observations. At the same time, it’s also an excuse for me to reflect on some enjoyable past gaming experience – and maybe some of you will also have played these games, and have your thoughts to share as well! Regardless, I hope this is an interesting and rather different entry to read, but either way, we’ll be back to the normal devlog next time :).

So let’s get started:

One Must Fall 2097

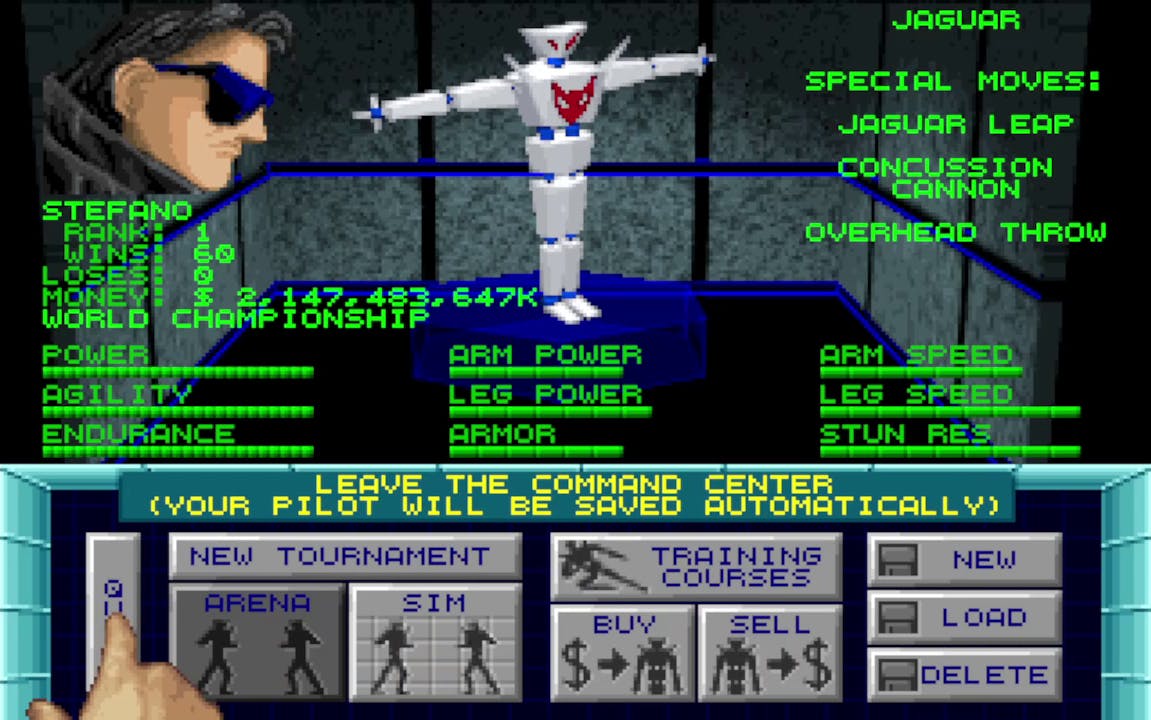

This probably remains, to this day, my favourite fighting game. Set, if memory serves, a couple hundred years in the future, the game sees you controlling hundred-foot high robots in gladiatorial arenas, as part of the sport that has become the world’s favourite pastime (this was of course released long before the 2011 Hugh Jackman film “Real Steel” came out, and had basically the same idea – though I do actually think the film’s pretty charming). There are 11 robots to pick from, a range of stats to improve and adjust, each robot has its own distinct playstyle and a fairly decent suite of moves and special moves, and the pixel art is all honestly top-notch, with a huge amount of care having clearly gone into animating all of the robots, as well as all of the other work in terms of backgrounds, settings, arenas, menus, character art, and so on. Indeed, my first mod of any significant size was in OMF, where I was able to decipher the game’s C++ as a child to a sufficient extent to add a new tournament, with some interesting fighters who had interesting colour schemes, and also begin to understand how the game’s AI played out, and how fighters could be made easier or harder on that basis as well. The game had some interesting secrets, a surprisingly solid story for how sparsely it was told, a lot of different ways to play, and just a really fantastic futuristic aesthetic the blended mechs, cyberpunk, and a strong sense of a media-saturated reality. As an aside, I also really like the visibility of the player character’s hand in the above picture, while you’re adjusting your robot – it reminds me of things like Doom, Duke Nukem, Hexen, and things like that. It was a nice touch then, I still think it’s a nice touch now.

Anyway, the thing we’re really interested in here is the news reporter feature that OMF employed.

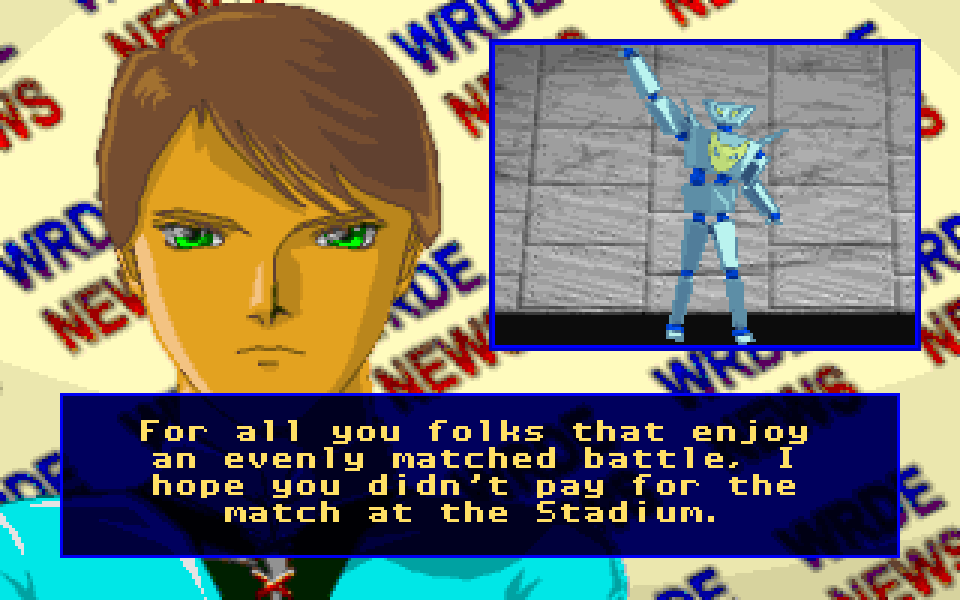

After each fight the player would be treated to a look at a news programme which was reporting on that day’s combat. As a child, I remember I was very impressed when I very quickly realised that the comments of the news reporter, sure enough, had some fairly accurate relationship to the way the fight had gone. Being very young and knowing nothing about programming, I was also struck by the fact that the news reporter was able to say my character’s name! Now, of course, I realise this is not the most impressive of programming tricks, but at the time it really struck me as a lovely addition. What was more impressive though, and far more important, was as I say the fact that the news reporter’s comments would have a relationship to the fight. If it had been a complete clean sweep, then they would say that. If it had been an incredibly close match, where the winner had only a fraction of health left when they dealt the final blow, then the news reporter had the ability to comment on that. If the fight had been somewhere in the middle – the winner had perhaps lost half of their health, but had still emerged victorious – then the news reporter could, again, comment on that as well, expressing appreciation for the fact that it wasn’t a complete slaughter, but also noting that ultimately the fight only went one way. I believe this latter option has two sub-options, i.e. one for the victor losing some health, but ultimately not that much, and one for the victor losing much of their health, but still having a fair amount left upon winning. The reporter is also able to talk about what particular arena the fight was fought in – again, I now realise this is trivial – which further gave young Mark a sense that somehow the game was able to properly talk about, and understand, the bout I’d just fought. And, on top of all that, it even took a screenshot from the end of your match, that you’d just fought, and added that (and several others) into the news report! That’s a stroke of genius as well, honestly.

This was one of my first experiences with what PCG can do for a game’s feel, and the player’s experience of it, and how even a very simple algorithm can be used to create something really compelling and unique to every fight. I loved this feeling that the game had been paying actual attention to what the player had been doing, and that one’s actions in the arena in this sport hadn’t just been self-contained and separate from anything else, but could be given a narrative, and a meaning, as a result of this news report. It was also a very effective tool for suggesting a world much larger than the game in fact had. There was no audience, of course; there were no fans with viewers one could ever meet or see or interact with, there were no external parties, and although the game’s story told us that this was a wildly well-viewed and well-followed sport, nothing else in fact ever confirms this explicitly. The game overall does a good job of building up this idea that as a famous fighter one does indeed become, famous, and the news reports were really important part of this – even though they didn’t have that many options (and even as a child I quickly came to recognise the four main archetypes of what the news reporter can say) they still really did a huge amount both to give a sense of story to the players actions, and to apply this far wider world in which the player’s achievements and skills are being viewed, appreciated, dissected, discussed, and so on. It was a remarkably effective tool to not just achieve all the objectives I’ve listed in this paragraph, but also as a way of letting the player reflect back on their own skills. Was the previous match an absolute slaughter? Or was it extremely close? Thanks to the news reporter each fight took on just a little bit more weight, and became a thing that one could reflect on when trying to improve one’s skills.

My inspirations for URR features are often of the sort “[a game] did [a cool PCG thing] on a very basic level with perhaps a dozen permutations – how about we push that into the tens of thousands?” – and OMF:2097 is no exception here. Having the game tell the player what they just did, or what just happened – and present it in a narrative – is just such a rich idea, both for giving the player’s actions and decisions extra weight, but also for making the player feel like they are truly present and grounded and exist within this world. Readers will remember that I’m currently working on the player’s journal – probably the only book you’ll be able to open in 0.11, but that’s a huge milestone by itself – one section of which will recount and track the player’s progress, actions, adventures, encounters, challenges, and so forth. This meant developing a system which could indeed write a narrative about the player’s actions, and I was in fact inspired by the newsreader here when I was developing that system for URR. I’m currently in the process of transferring that from my testing file into the main game, and there will be a future blog entry about that soon, but I really do think there’s something just so compelling about having the game frame, and talk about, what the player has done, that gives it a really extraordinary weight and meaning which other techniques don’t necessarily get. It’s also very unlike many games with quests which update you on the quest progress, such as The Elder Scrolls games, because those are prewritten texts which you know you’re going to advance through. They wrote a journal entry for advancing the quest, sure, but did they write a journal entry for deciding to abandon it and instead just consume massive amounts of three hundred year-old hallucinogenic wine? No, they didn’t – but URR can give you a journal entry for that, no problem, even if I (the designer) had no idea the player was going to go and do that. I think the newsreader is a testament to the power of developing systems that can write intelligent sentences for what the player has done, is doing, or might do, and although done in quite a basic level in OMF, it’s something I want to take – and am taking – so much further.

Freelancer

I’ve only ever played one MMO in my entire life – EVE Online. it’s an absolutely deranged and unhinged game, of course, and I had to quit after just a few years simply because it took up too much of my time , even while I was sad to leave behind its astonishingly fascinating player-created politics, battles, espionage, and all the rest of it. There really is nothing else like it. However, for the normal human who doesn’t have an infinite amount of time to spend on fictional space politicking and imaginary interstellar spreadsheets, Freelancer was a wonderful experience in my teenage years. Although obviously I know now that there were many progenitors and antecedents to Freelancer, at the time I had never played anything like it, and I was absolutely blown away by the size of its world, the quality of its voice acting and story, its vast range of places and ships and weapons and things to see, its subtle but nevertheless present exploration aspects and the ability to hunt down interesting secrets, and just the pleasure to be found in spending time in that world, which felt at least somewhat alive, as well as the quality of the space combat, the excellent music, and the honestly stunning visuals, which have still to this day barely been matched when it comes to spaceflight games. It was one of the very first games I ever played where it felt like a genuine world was present here. Although I can’t imagine I played it for more than a year in total, or perhaps it wasn’t even beyond six months, I found a huge amount of rewarding stuff in the game in pursuing the main plot, pursuing all the side things to be done, and just delving deeply into some of the more obscure systems and hidden stuff the game had. And, of course, the fantasy of being a roguish and renowned space pilot is hard to resist for any teenager.

All that is fine and good, but what is of interest to us here, is the job board.

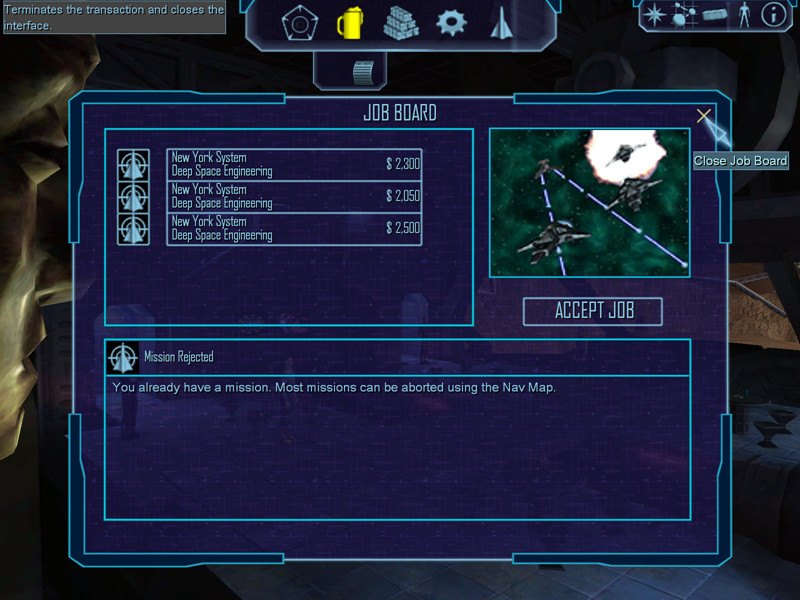

Perhaps taking its cue from various television series which have overall plots advanced in some episodes, but most episodes were one-offs with nothing to do with the main story (e.g. The X-Files), Freelancer had a progression and quest structure whereby every now and then the player would be offered a mission that would advance the core storyline – generally when they had achieved a certain level of ship and a certain degree of wealth – but in-between those you had to go out and find your own work in order to get those same advances, in order to get the next story missions. Although there were a number of ways to an income, the most prominent was by taking on – as the game’s title suggests – freelance work as a space fighter pilot, trader, escort, and things of this sort. These jobs were found on the job boards in planets and space stations, where different corporations would offer you different missions, consisting of several key types – transport something, kill something, and so on. Beyond these basic types however, there was also a lot more variation here, as the text would be to some extent procedurally generated to tell you about the mission, and the location was also generated, likewise the rewards, the threats, and pretty much everything that there was here, actually. I remember when I first played this, I didn’t appreciate that these were generated, and I thought that the game had a massive bunch of side missions to to do in between the important ones. As the game went on though, and I both started to see a few repeating themes in them, and to understand that there were far too many here to possibly have all been handmade, I found myself really very immersed by these missions, and what they seemed to imply about the game world.

Much like the above example in OMF, the job boards – and the range of missions, factions, and so on – did a fantastic job of evoking a much larger and more dynamic and always-changing world than the game in fact had. The fact I include the latter part of that sentence does not mean I’m making a criticism here, but rather the reverse of course, as I think it’s a tremendous tool that shows how well these things can be created in the player’s mind, even if they aren’t necessarily reflected within the game on a technical or design level. They also, of course, added significant replayability and variety to what the player was doing, but I think that’s a comparatively less interesting facet, given how many games can procedurally create basic quests and things of this sort. Rather, it’s the stuff that’s one step “outside” the actual mechanic itself which are really of interest – the idea that this is a world where there’s always jobs from corporations and factions and nations and pirate groups to potentially be taken, there’s always competition between these, there’s always going to be work for the aspiring pilot. It’s these that spoke to the bigger world, its nature, and did so so effectively. Freelancer, as some will know, was originally intended to be an even more ambitious game than the final product we actually got. This is not a criticism – I and many others still think Freelancer is fantastic – but a lot of those would have contributed, as well, to this sense of a living world. Nevertheless, these quests, especially when coupled with the faction and corporation system, gave a real sense that that this was an active world, that there might be other freelancers out there doing the same kind of work, and that there were many factions competing for dominance. Those factions never genuinely changed in dominance, as they do in something like EVE Online, but it’s a very convincing trick, especially for the younger player. These job boards suggest that there’s always action and change in this world, there’s always pirates to be fought, there’s always trade goods to be moved, and hence there’s always work for the aspiring space freelancer who knows their way around the systems, and knows their way around a missile launcher. Even if a long-term player will see repeating patterns soon enough, there’s a lot of variety here, especially when you factor in how many factions there are, how many systems there are, and so on. Each one feels new, and organic, and distinct to your world, and its evolutions.

Whereas OMF lives in my brain as a demonstration of the power of using PCG techniques to add written (or screenshotted!) narrative to the player’s actions, as well as some ability to suggest a bigger world, Freelancer showed me how to go much further and much deeper in that second direction. Now two decades older I would of course be looking for a game to have genuine changes took place as a result of one’s actions, much like EVE does, but that isn’t to overlook the value of these sorts of ideas. I can very easily see some of these be incorporated into URR – we’ve already got the “Wanted” posters for bounties appearing in some nations, and as both nations and religions become more fleshed-out factions, and more gameplay mechanics come into existence, these are ideas I’ll definitely be pursuing. As I’ve mentioned in previous dev blog entries, I really like the idea that most of the player’s major actions will increase friendship with some factions and decrease friendship with others, and that this will become something increasingly challenging as a game progresses, adding difficulty in the later game not just via increasingly difficult and obscure riddles and duels, but also because more and more of the game world will be opposed to you – even while, at the same time, you will have more allies as well. As with the OMF example, I do like what Freelancer did with this, but I will again of course be going about a thousand times deeper here. I want every sidequest to have a huge amount of story detail with it, to create real effects within the game world when completed, to accurately reflect factions and their objectives and their relationships with other factions, and so on so forth. In many devlogs I feel those ambitions are extremely bold and perhaps overblown, but in URR we’ve already got 80% of what’s needed in place as I write this. Yet while I do think this will be great in terms of gameplay, it’s much more the setting and the feeling of a lived-in world which Freelancer taught me about with these job boards. I think it’s a fantastic idea, and just waiting to be expanded into something far bigger.

Neopets

It’s hard to pin down the most defining games of my childhood and teenage years, essentially because I spent every second that I could possibly spend playing games, on every console and platform and piece of hardware I could possibly find play games on, and as I look back now in my thirties, so many of these had so many strong inspirations on what I’m doing now. Yet, if we had to “rank” games, we might choose to rank them according to how many hours I spent on them in my first eighteen years of life. Doing so would show that the Command & Conquer games are very high at the top of list, and likewise the Counter-Strike and Halo games, but another right up at the very top of that list is Neopets. Neopets was launched in 1999, and I believe I started playing in 2000. I found my way to it because I, like every millennial with any kind of tech or game interest, was utterly and completely captivated by the internet and its possibilities, and I was specifically looking for virtual pets at the time. Many will remember that the early web, and 90s computing in general, were absolutely replete with weird little tools or weird little programs or weird little toys that one could install, such as those which would sit in the corner of your desktop and do various things, or desktop backgrounds which involved goldfish you had to feed, or screensavers (remember those?) which were to some degree interactive, or things of this sort. At the time I’d really fallen in love with customising my user preferences and layouts on Windows 95 and especially Windows 98, having a lot of fun with custom backgrounds and custom sounds and custom colour schemes – including those which, I now realise, were quite painful on the eyes! – and I thought a virtual pet would make a wonderful addition. I found Neopets, was taken by the charming aesthetic, and signed up, thinking I was going to download a trivial little thing for my desktop which I might play with, maybe for a couple of minutes a day, for a few months.

How little I could have anticipated what would actually happen.

There’s actually a tremendous amount of interesting stuff which I think can be said about Neopets – indeed, I’m considering writing an academic book about its game design and lasting impact at some point in the next decade – but here I want to keep my focus not on most aspects of the game’s design, nor my own Neopian adventures and accomplishments across a wildly captivating and entertaining eight or so teenage years, but rather on what were called “plots”.

A “plot”, in the Neopian vernacular, meant a site-wide event that took place generally over several months, and would involve a story that the Neopets team had written up and were presenting to the players, as well as generally a large number of unique opponents for your pets to battle in the “Battledome”, and – crucially – a puzzle element. What’s fascinating about these is that the Neopets team quickly realised that if you have a site with over 10 million active users, any fixed puzzles are going to be solved essentially instantly, and even more obscure ones will be cracked relatively quickly (hours, days). One of the earliest plots had a range of purely fixed puzzles, and they were all deciphered – if memory serves – by the collective efforts of the community within a couple of days. Although the developers did not as far as I know comment on this, when we consider the difficulty of the puzzles in question, I’m pretty confident that they were not expecting this to be cracked within a day or two. Part of this was also to do with the fact that while Neopets branded itself as a children’s site, there were a lot of teenagers and young adults on it, and – speaking from experience and friendships forged on the site – this “older” demographic tended to be a pretty clever bunch of people, particularly in an era where still not everyone was at all comfortable with the internet or with digital games. As such, to address this, in later plots the Neopets team took two significant steps. Firstly they added a lot of steps which were not particularly puzzly, but required a large volume of collective work and effort from users. For example, during the “Lost Desert Plot” – which is probably the exemplar, and to this day remains one of my most enjoyed and most fondly recalled gaming experiences, across all games and genres – several of the steps in the plot required hundreds of thousands of players to contribute to, for instance, digging out a pyramid, then filling that pyramid up with furniture and items, and various other other things of this sort. Players of course got rewarded for these, and that feeling of contributing to something bigger was very palpable, and very enjoyable. Again, it made the world feel alive – especially because, this time, it actually was!

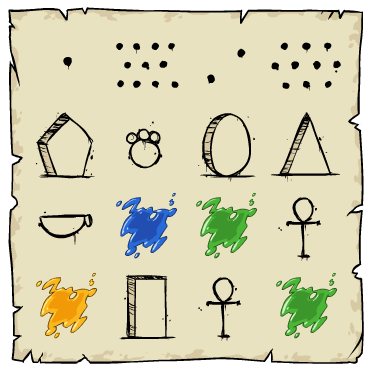

The more interesting part for us, however, is that the later plots, such as the LDP, did include significant procedural content generation in the puzzles and hence solutions given to each player. The idea would be that players had to work together to figure out how the puzzles could be solved, but each player had to perform that action themselves. Long time readers will see something quite similar to what I expect to happen in the coming decade with URR in this description. Once the game is a little more feature-complete I expect people to start discussing certain riddle archetypes, what certain phrases mean, things of this sort, but none of that means that a player can simply look up a solution online. They’ll only be able to look at the tools, but not the actual solution. Neopets may well have been the first game ever to really do this and to really explore these techniques (which is kind of remarkable, actually). In the Lost Desert Plot, for example these techniques were applied extensively. Everyone had access to an area called the “Temple of a Thousand Tombs” which was a unique labyrinth that differed for each person who explored it. Each player was also given a set of runes to decipher, which were always distinct and had different interpretations, as well as each player being given a series of different sequences of colours and lights, which again had to be interpreted separately. Not just did this mean that each player who wanted to complete the plot had to do their own puzzle solving, but it also – I suspect – slowed down (in a good way) the community’s effort to unravel them, because the community had to decipher the abstract mechanics that the puzzles operated by, rather than specific puzzles themselves.

(See the inspiration??)

At the time, I was really blown away by these techniques, probably more so than the PCG ideas I’ve mentioned in the above two games – probably because there’s a far more sophisticated thing going on here, and because Neopets was ultimately more central to my teenage years than either the above games, even as much as I enjoyed them both and look back upon them very positively. I was very impressed simply by the ability to give each player a unique puzzle, and it was such a joy to be part of these communities trying to deciphering solve these things – although I don’t mind admitting I never made any significant community contribution here, since I hadn’t yet got into cryptic riddle games and learned how they think – but giving each player though and puzzle also generated distinct feelings as well. You couldn’t rob yourself of the feeling of accomplishment by looking up answer, as you simply had to do the work yourself to figure these things out. The threshold for this wasn’t trivial, by which I mean it wasn’t as if one just looked up the answer and then applied it to your own stuff, but rather there were several steps and interpretations which needed doing and it was very easy to go wrong, so complex were some of the steps. I remember at the time some walkthroughs and guides saying things like “this is all we can do to help you, it’s up to you beyond this”, or other statements to that effect – all very impressive and very compelling to the keen player. Equally, the puzzles didn’t lose any complexity or challenge because they were made distinct for each player, and because the processes required and the data being manipulated were both sufficiently complex as to avoid this outcome. These plots, particularly the LDP, actually one of the strongest inspirations on URR – although not one I think I’ve actually talked about before. They demonstrated that these ideas were possible, they demonstrated that particular dynamics between one player and the wider community could be developed here, and they were simply a joy to explore and to decipher and to become really deeply involved with, seeing just how far the rabbit hole went. As with the others, I’m trying to scale this up by about a thousand times, but whenever I find myself with doubt over the game’s design and direction, I remember how avidly hundreds of thousands if not more people enjoyed the Neopets plots – and I know, in my soul, that I’m on to something good here.

(Even if it takes a bloody long time to make it when you’re a one-person dev team, working in your spare time.)

What next?

Thanks so much for reading this blog post, everyone. I really do hope you all enjoyed it, and got something interesting from it. If you also played any of the three games mentioned, I’d love to hear your experiences, so please do post a comment. Equally, of course – do you have early memories of other games with just some little bit of procedural content generation in them, which really stood out to you as doing something interesting? If so, please do tell me about them! In the meantime though, I do hope you’re all keeping well, and I’ll be back in two weeks with a new dev blog update for you all.

Thanks again for reading, folks, and I’ll see you all in a fortnight!

Never played any of these games, but they’re fascinating to read about. I’ve seen random missions like that in a browser-based RPG called Pardus, but they weren’t well designed. For me it was classics like Elite or The Sentinel anyway, and later roguelikes. Fallen London, too, inspired my own personal flavor of text-based RPG after a couple of design iterations. Too bad I discovered Space Trader too late to have it influence my game design work. Oh well. Can’t have them all.

Thanks so much Felix! Pardus is a new one on me – a quick Google later, and that looks really interesting. I have got to play the Fallen London etc games at some point! They’re absolutely on my list. Not PCG-related, but speaking of browser-based multiplayer games from the olden days, I still have fond memories of a weird little game called “Secrets of War”, about competing settlements on an alien planet (I think?). Very strange but quite enjoyable, and really settled into my brain a little bit…

Thanks for the interesting discussion of these games — I was never into Neopets and had no idea that there were events and puzzles! There’s actually an annual community event going on now in Fallen London called “Estival” that’s similar to the Neopets plots you described. There are fixed puzzles (many of them fiendishly clever) that dedicated players can solve and then share the solution with the community. However, there are also certain events that require a total player contribution in order for the story to advance. This year the game is trying something new by allowing players to bypass puzzles after the community contribution aspect is complete, in order to help out people who aren’t involved with the social aspect of the game and would otherwise miss out on solving the puzzles. It’s an interesting way to mitigate player frustration.

The job board in Freelancer also reminds me of one of my favorite old games, Mechwarrior 2: Mercenaries. In the game, you accept missions from a contracts database that includes a mix of fixed story-related missions and randomly-generated missions (IIRC, you can actually ignore all of the story missions up to nearly the end of the game if you want to). On release the game gave you fixed salvage rewards after story missions, but this was later patched to “dynamic” salvage which rewarded players for being careful and thinking like a mercenary (such as by destroying enemy mechs with headshots, enabling the player to salvage the mech for sale or repair).

The game also has a player journal that is updated from the story missions, and a news database that is added to as in-game time passes. Although these entries are all fixed, they are still amusing and make the world feel more real. For example, the tutorial missions are run by a crusty old mechwarrior trainer named Sergeant “Dead-Eye” Unther, and much later in the game there’s a news article about how he is now on the run after abandoning his trainees in a war zone! It would be neat if it were more like OMF and dynamically generated articles (or variations on fixed articles) referencing the player’s actions and accomplishments (or lack thereof).

Crowbar, thank you so much as ever for such a great comment – and I am so glad you’ve told me about Fallen London and these Estivals. A quick Google took me onto the Wiki, and having a quick look at the recent one, and – wow! I think these are actually really similar in both concept and execution! I had no idea any other big multiplayer worlds had done / were doing anything even remotely like this, honestly. I’m 100% going to give this a closer look, and maybe even play some myself? I’m very intrigued.

I haven’t played MW2, but I did enjoy MechCommander Gold and MechWarrior 3 in my teenage years – a lot, actually. I knew nothing about the wider universe (and since becoming an adult I have discovered that the term “wider” barely even begins to cover it!) but I enjoyed both, especially MCG’s Darkest-Dungeon-esque pilot permadeath thing, which at the time seemed really novel and I liked the sense of a genuine campaign that it brought with it. I like the mission structure you describe though, I can definitely see how that would work, and great to see another news mechanic! I really do think things like that have a lot of potential. I can imagine a near-future URR headline: “Ancient relic found to be missing from Chapel of the Winged Lord – authorities clueless…”

Freelancer is absolutely fantastic and I’m saddened that I had forgotten about this game. My brother and I used to sit around the same PC and he’d play it and I’d watch. He was younger, but I didn’t care, it was just such an immersive game for the time.

It is/was fantastic! I entirely agree (and I love those sorts of memories – for me it would be with my best friend when I was young, playing plenty of singleplayer games together by switching around the hot seat). Apparently there’s actually a huge and very detailed multiplayer mod for Freelancer, which has a large player base? I’m debating looking into it – probably won’t be this year, but maybe next year…

Hoho, I could be wrong, let the experts correct me: in the X series, the dynamic world and tasks are generated relative to the situation in the world, and their implementation really does physically affect the world. All resources move around the world and have finite reserves. The X series, namely X4, is an evolution of the ideas of Freelancer. So to get acquainted with the ideas of generation, I recommend trying this game.

Hello Denox, thank you for the comment and welcome! I confess, I hadn’t even HEARD of this series, though a quick Google later has intrigued me. I’ll definitely look a bit further into these. Thank you for the suggestion!