Hello everyone, and welcome back to the new and improved fortnightly Ultima Ratio Regum development blog. The title of this week’s post is, I suspect, one that nobody on the planet saw coming – although after last fortnight’s shock announcement, perhaps some did? – but it’s one that I’m very excited to to talk about. For the last few months I’ve been slowly but surely integrating sound effects into the game, and also of course working out how to actually integrate music and background sound into the game as well, and a huge amount of progress has been made on both these things. Although this was never a priority, it has come together with surprising ease, and I’m actually very excited to see to show off what we’ve been able to get going here (I’d say this element of 0.11 is now around 50% complete). So, let’s get started:

playsound3

As noted last time, the decision to start integrating sound and music and background audio into the game came to me quite suddenly. As well as the desire to ensure that 0.11 really stood out from everything that had come before, it was also definitely spurred on by some recent things I’ve been thinking about – which I’ll talk more about in the in a big summation post for 0.11 and development up to this point which I’ll be posting after I post the 0.11 release – in terms of my own abilities as a programmer and both the level which they’ve got to, and the importance to keep pushing them and becoming a more skilled coder as time goes by. I’d always thought of music and sound is quite intimidating things to work into a game. This was in part because the tcod library has no specific music or sound implementation (EDIT: I stand corrected on this! See the comments section below), in part because I worked these things up into my head as being incredibly challenging precisely because I hadn’t any experience in them (ditto in game projects I worked on when I was younger, before URR), in part because most classic roguelikes don’t really have any sound implementation except in specific ports or versions (so maybe I… don’t need them?), and probably also because in real life I’m really not a very aural person at all, whereas I am an extremely visual person. Although these things were all subconscious, I’d always just placed sound and music into a category of things that seemed very intimidating to start exploring, and seemed almost unnecessary, and where I might wind up spending days or even weeks going down the rabbit hole of code, never to produce anything usable at the end of it.

However, a few months I was grabbed by desire to give this sound thing a go. I did some quick Googling for Python libraries which handle sound, and although pygame came up, I found one specialised just for playing sound, called playsound3. I took a quick look at the documentation and this looked like it might do exactly what I was looking for. So I got it installed, and started playing around with it, and to my absolute astonishment I had background music playing within only about ten minutes of installing the thing. Almost immediately after I created a simple implementation to have a sound play when a particular in-game action occurs, and sure enough – to my even greater amazement – I soon had a sound playing successfully. I felt both very pleased with myself for having been able to make this jump, but also slightly amused, in a wry and self-reflective kind of way, that I’ve been putting this off with such intimidation for so many years, and found that it took me about half an hour’s work, in a single afternoon, when I hadn’t even planned to do this and was mostly working on some academic writing and just fancied a quick break, to actually start developing sound implementation. Whoops. Anyway, I was very happy with how the sounds were playing – I just found some quick placeholders on my computer to test the thing – and I was pleased to find that it was using a different thread from the main game, and thus actions and even waiting for a for keyboard input could be successfully handled while the music continued to play in the background. However, it was soon pretty clear that playsound3 had two potential issues here. The first of these is the is that it has no native implementation for looping a piece of music, nor for reducing or increasing the volume of a piece of music, e.g. having one fade out as another fades in. Imagine the player changing from walking around on the human scale map to exploring the globe on the world map – I would of course the human-scale music to fade out, and then some kind of travel music to fade in once the player’s doing stuff on the world map.

Equally, the lack of looping functionality was a serious problem. Obviously if we talk about background music, or even just background sound effects for things like rain, we want these to be able to loop – and playsound3 doesn’t have a way to do the looping. Now, it was soon apparent that it would be comparatively trivial for me to implement loop coding myself, except for the fact that some of the keyboard inputs in URR are handled via tcod’s check_for_keypress function, and others are handled via the wait_for_keypress function. What this meant, essentially, is that the while I could trivially write a piece of code to check whether the background music is still playing or not (and if it’s not then play it again), with so many wait_for_keypress implementations, the game pauses there until the player next puts in a keyboard input – and so can’t be continually checking for the background sounds having concluded, and hence needing to be restarted. I then spent a while experimenting with how easy these would be to replace, and found that they would in fact be quite demanding to replace, given that all the code around a given keyboard input detection is built with the expectation of waiting for a keypress rather than checking for keypress, i.e. completing a block of code and showing something sensible to the player and then awaiting a new input. I played around with this a bit, but I did struggle with to find an effective implementation here that wasn’t too CPU-intensive. The more thought about it as well, the more I increasingly realised that even if I was able to handle this looping issue, I still wouldn’t be able to handle the volume issue, resulting in tracks having quite a sharp end or beginning when you’re transitioning from one thing into another. As such, I decided that after 14 years, the time had finally come to check out by far the most well-used and well-known library for Python games – pygame.

pygame

So I got the thing installed, but quickly ran into some compatibility issues with the version of SDL I’m currently using. I’m not in the mood to install things will change things that might require significant change to URR’s codebase right now, so instead I uninstalled that and found a recent but not totally up-to-date version of pygame which was happy with the other installations I was using for URR. With that installed, I started to play around with the “mixer” functionality in play game, and was satisfied that within just a few minutes I had all the same things going that it had with playsound3, i.e. the ability to play background music, and ability to play sounds, although pygame also usefully enables you to just loop background music by default, and also has functionality for reducing and increasing volume. I didn’t explore those immediately because I wasn’t initially sure what – if any – background music we were going to have in 0.11, but the sound effect stuff was very exciting. Before I could properly get into it though, I discovered a strange bug whereby if there was a background sound playing in playsound3 – even if it was a track of looping silence – sound effects with playground3 would play instantly, as they should. However, without a background sound looping – again, even just silence – the sounds would play on a delay, and this was also true of background music and sounds both in pygame. Yet having the background sound on pygame, and the foreground sounds on playsound3, worked perfectly. I did some Googling around this and couldn’t immediately find a solution, and but the code was written in such a way that I could have a background silent track looping to avoid the issue, so for the time being that’s the implementation we’ve gone with, and it ensures that all sounds play as fast as a blink of an eye after they are triggered, rather than after short delay. I will continue investigating the source of this bug, and whether it’s to do with my hardware, my software, the libraries, or something else, but it’s also one of those things where if it works, don’t probe too far into why it works – just go with the working solution. And thus, right now URR has a looping background silent track (via pygame) which enables sound effects (via Playsound3) to always play instantly. Unless I run into serious issues with this implementation, this’ll do for the time being while Nik and I continue to work on the official soundtrack.

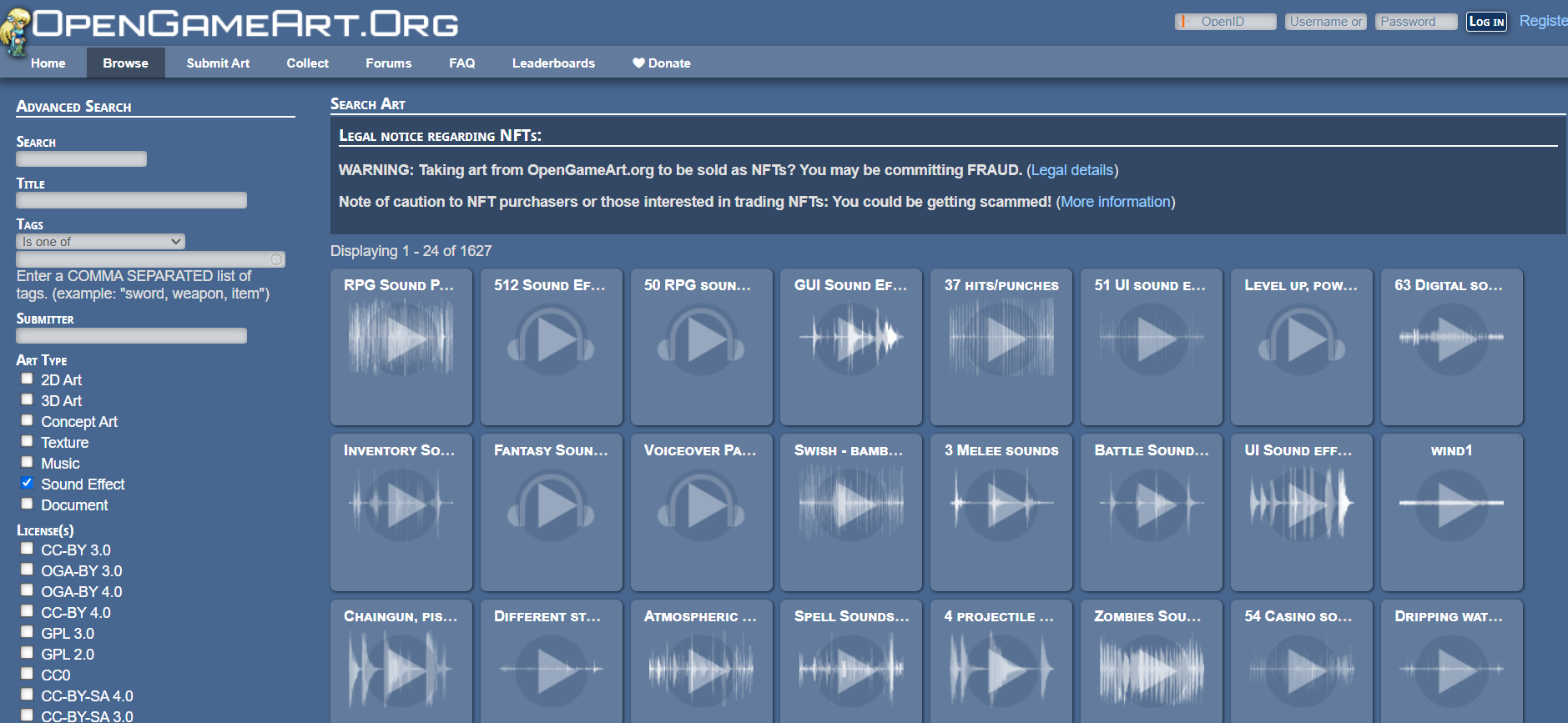

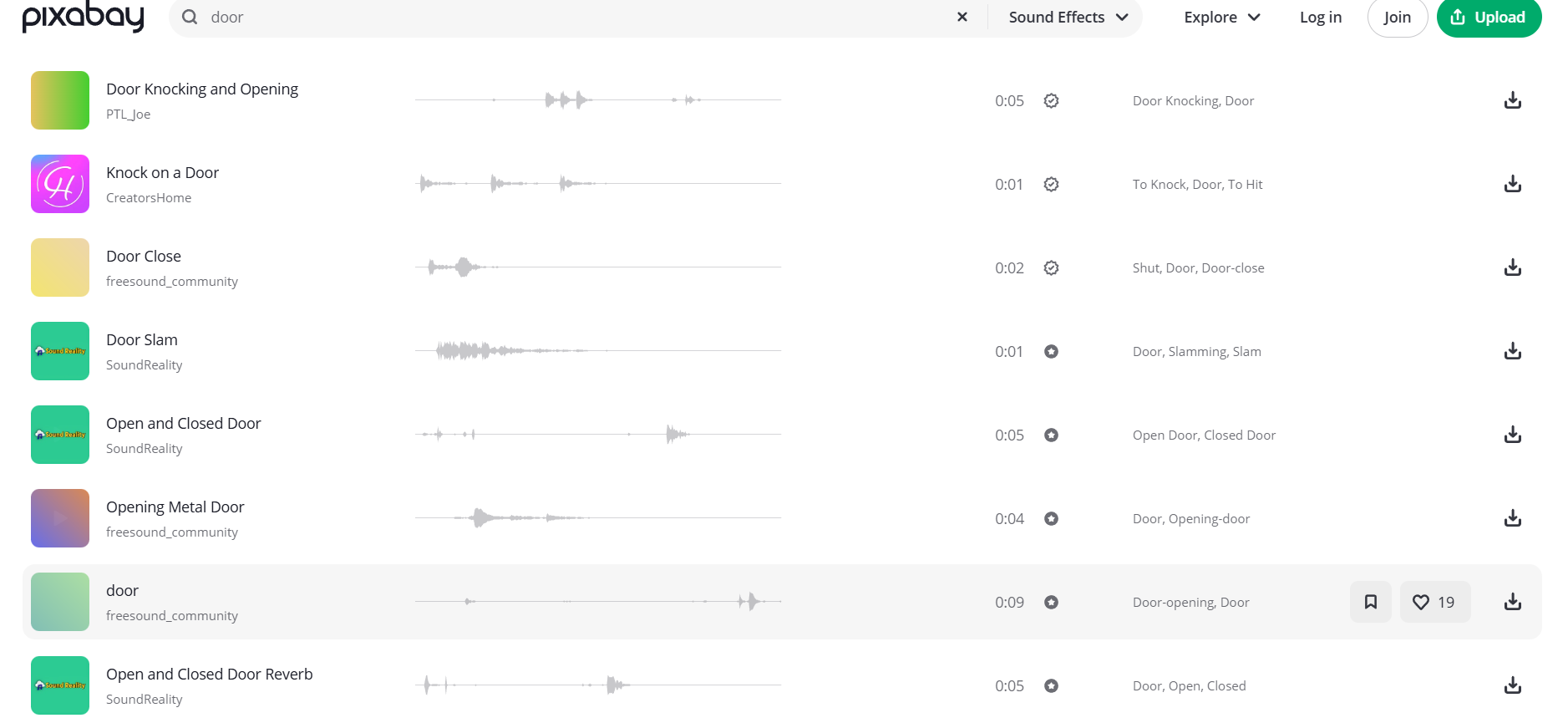

With all this sorted, then, the real fun began – finding sounds! A quick Google pointed me towards a number of sites with large databases of free sound effects, which require neither royalties nor license, and I set about searching through these for sound effects that I would like. Given that the game is turn-based, I really wanted to find very deliberate and clear sound effects that would give very active and responsive feedback to what the player is doing, to mark out actions as as being distinct and important, and to hopefully offer an overall extra layer to the game in the realness of the world (which perhaps hadn’t been there before). I also knew it would be very important for sounds to be very brief in most cases and not to linger on, drawing attention away from gameplay, which felt like an important requirement in a turn-based game. Equally, as longtime readers would know, I have a real appreciation for games which have extreme detail and adhere to the “The Dev Team Thinks of Everything” philosophy – i.e. I would want sound effects to handle all potential scenarios for in-game interactions, even those which might be very rare, very unusual, very obscure, or indeed just not even seen or experienced by most players. I felt that was very important for really maximising the extent to which sound could be used to boost and increase the richness and verisimilitude of the game world. So, with pygame and playsound3 both present and working together – albeit rather strangely – it was time to start exploring, and finding some sound effects to start integrating into the game, and bringing the world to life.

Adding sounds

The first sound I tried implementing was a simple tricking or tapping sound for scrolling through menus, such as the main menu, saving loading, or large records such as the in game encyclopaedia. Naturally I didn’t want this to be too dominating a sound, as you might hear it a great deal within a short period, but I wanted to give a sense of immediate responsiveness from the game when the players doing this, particularly on the main menu. I found one I liked but it wasn’t quite perfect, so this is where I started to teach myself Audacity (which, as an aside, is a great name for a piece of audio software). As above, audio and sound are really not things I’m comfortable with – so far! – and the program was again quite intimidating, but also turned out to be pretty easy to use, particularly in terms of simple tasks like reducing the length of sounds, or making changes to sounds, or taking these free available sounds and just adjusting and polishing them a little bit to get them far closer to what I was looking for and what I wanted to implement into the game. After a little bit of editing I then put this simple tapping or clicking sound into the menus, and I was very happy with with what it did – indeed, I was amazed by the extent to to which even something as simple as that made the game feels so much more active, so much more responsive and lived in, than it had previously felt. In hindsight, perhaps I made a significant mistake here by leaving sound design too so long in this project, but I don’t think it’s particularly productive to beat oneself up for those sorts of things. You can only do things when you have the right headspace to do that thing, and when one and one has at first initial burst of excitement and brainpower to to get over the initial hurdles and put things into place.

Anyway, after this, I decided to try out sounds for some basic in-game actions. I quickly found one for opening a door, and added this so it would activate whenever you enter or leave a building, and immediately again, I was astonished by this feeling of an extra dimension (meant in the sense of, metaphorically, an entire extra spatial dimension, not just “dimension” in the sense of “aspect”) that was instantly present once sounds were implemented. Suddenly doors felt less like just graphics on screen, and more like genuine objects which the player was interacting with and passing through. Again, even though this was the first ever sound effect implemented into gameplay, and although – obviously! – I’ve encountered many sound effects in many games, this is the first time I’ve ever played a game for 14 years, and then played that same game with a with a sound effect added. It genuinely took me aback, the degree of difference it made to to add something as simple as a one-second sound of a door being unlatched and opened. I know this might sound silly, but it was honestly a very striking change. This was actually a very exciting moment, even more so than the menu scrolling / ticking sound, because it really seemed to demonstrate to me that I was on the right track here in terms of something worth doing for the game, something which would add an extra dimension to 0.11’s release, and – importantly – was something that wasn’t even all that demanding in terms of programming. Again though, I just couldn’t believe how much such a simple addition brought into the world, the sense of physicality and materiality and the idea that an actual action had taken place, all things that this sound effect added to simple transition through a door between the inside and the outside. Astonishing.

Next – and at this point I was still doing this haphazardly, since I had yet to sit down with the goal of doing nothing but sound design, finding perhaps a hundred effects and implementing them all into the game – I went out and found a sound effect for firing an arrow, one for firing a bolt for crossbow, and a nice sound for something wooden – such an arrow or bolt – smashing to pieces. These were fractionally more challenging to implement since the code for a projectile is quite complex because it can hit so many things, and generate so many hundreds of different sentences to describe what it has hit and what the effect it had, but pretty soon I had a system which played the arrow-firing noise when you shoot something from a bow, the bolt-firing noise when you fire something from a crossbow, and the sound of something light and wooden snapping and smashing playing as soon as the impact animation plays (i.e. the arrow or bolt breaking apart upon impact with something). Naturally in the future, once we have combat, there will be other outcomes here such as arrows or bolts sticking into someone, or pinging off armour, and so on, but this was still a fantastic start. Again, it seemed to give so much extra weight and so much extra richness to the action that you had taken, and by adding a second channel of feedback beyond the visual, I was again struck by how much the actions leapt off the screen, after years of doing these and seeing these without sound. It’s in the difference as much as the sounds themselves, I think – like a sudden revealing of something I’ve been playing without for so long, but now it’s here, it’s fantastic and incredibly rich.

As a final aside, it is also interesting to note even at this very early stage of sound implementation (i.e. I only have a few in so far) that certain sound effects require certain special kinds of code. For example, the sound that plays when you go up or down a staircase has several steps in it and therefore takes few seconds. However, you could go up and then instantly back down again, and so on, causing the sounds to overlap. We don’t want that, so in this example, therefore, if you go straight back down or up staircase having this previously done that, and the sound is still playing, it just stops that sound and then starts the sound playing again. This prevents the player from just doing that endlessly and building up a reverberating set of the sound playing, but also reflects (pretty) realistically what this would sound like. I’ve also, of course, left “open” places in the code where future sounds can be inserted, and I’ll later on need to go back to sounds which currently only have one option to add a number of different options for the sound to play – the arrows and bolts hitting an object example is a really good case of what this will look like in the future. More generally though, I’m really pleased with the smoothness of the implementation here, both through the use of these libraries and through the bits of code that I’ve written on top of them in order to have sounds trigger when the relevant events are activated. The ease of adding in all these extra sounds has been honestly pretty extraordinary, I’m just so gratified that the whole thing has moved so quickly and so smoothly to a state where I can now start filling the game world with sound as well as music, and I think it will end up seeming infinitely more alive as a result.

What next?

So there we have it, friends – between this and the previous entry, I can proudly say that after only 14 and a bit years, Ultima Ratio Regum is finally acquiring something that speaks to the second of the two major human senses. I didn’t have any of this planned, but I’m incredibly happy with how the sound system is working here. While I’m only just at the very start of adding sounds in and we’ll have another entry in the near future finishing off this sound design discussion, it already adds so much to the players exploration of the world and the feeling of actually taking actions within the world, whether it’s firing an arrow, turning the page for a book, going up staircase, entering a door, buying an item, opening a chest, watching a valued item burn up in a fire, or whatever might be. I’m already finding it particularly fun finding sounds for obscure scenarios, again going back to what I talked about earlier in this entry about my overall design philosophy in terms of detail and always trying to think of scenarios that can happen, and giving the player a small reward if or when they do encounter that niche scenario. It’s really exciting! As ever, please do leave some comments in the area below if you’d like to, and please do share this around on the web if you think there’s people who will be excited by the implementation of sound into one of the world’s longest running roguelike development projects.

As ever though, thanks for so much for for reading, I’ll see you in two weeks time!

Tcod does have audio support, it’s just that it’s a very low-level and barely documented port of SDL3’s audio streams. Looping audio, fade effects, transitions, etc, are all supported with the catch that you’ll have to implement the streaming logic and effects yourself using Numpy. It would be on SDL’s audio thread too, so blocking for events won’t stall the playback of looping music. Tcod had an audio mixer for its port of SDL2’s audio API but SDL3’s audio streams ended up being powerful enough to replace the concept of a mixer on their own.

Hello Kyle, thanks so much for the comment! Ah, I stand corrected – I’ll actually make sure to check that out if this current implementation doesn’t work. That sounds interesting, though also potentially more complex than using something like pygame which, from my understanding so far, seems to have a lot of the relevant material already implemented. I appreciate the correction though! And if I run into problems with what I’m doing on sound at the moment, I’ll absolutely look into it…

It sounds like you’ve been enjoying this process of adding music and sound effects. That’s great! It’s good to mix things up a bit by adding a new and interesting feature, especially if you expand your own capabilities int he process. I’ve never put sound effects in games, but finding and adding appropriate music is one of the most fun parts of creating a game to me. For sound effects, I’m sure you’ll find and implement some good ones. I have one small suggestion: maybe you could find or commission some unique sound cues for key repeating moments in URR (such as when you make important progress on the main puzzle, etc). Something akin to the chest-opening sound/music in Legend of Zelda or the treasure chest theme in Vampire Survivors (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vZql1Y1IP3s&list=RDvZql1Y1IP3s); a short music or sound effect(s) that immediately becomes associated with the game.

Your mention of how adding a simple door opening sound completely changes one’s perception of the game reminds me of when I first started playing Cataclysm: Dark Days Ahead. This was a years ago, before the game had sound or music by default, and you had to manually download and enable sound packs in the game. I had trouble getting them to work and played without sound, and it was fun. But later, I installed an updated version of the game that had native sound and music, and as soon as the title screen loaded I was unexpectedly greeted with this haunting, chilling music that set the mood perfectly (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kbqFvhO6nC0). It makes, as you’ve noted, a surprisingly big difference in how a player experiences the game.

Thanks crowbar! You’re totally right about the enjoyment of mixing things up a bit, and indeed (as I’ll note a bit more fully in next fortnight’s entry) there have been other reasons too why I’ve been working on some of this stuff as well rather than more programming-intensive activities. Re: unique sound cues, I actually love this idea, and I think it’s a stroke of genius. Really pleased you suggested it – I know exactly the sort of iconic jingle you mean, and finding some equivalent would be awesome. I’ll talk to Nik about it, and do some looking around on free sites as well.

And – yes, totally! So different, so different. Maybe I should have appreciated it before, but, at least we’re here now. I really am excited to see how URR plays with a soundtrack *and* sound effects though. My goodness…