Friends – welcome back. I was planning on doing a main devlog this fortnight, but the stuff I’m working on for that update is getting bigger and more comprehensive and exhaustive as I work on it, so I’ve decided to save it up for a big start-of-year devlog post instead (look for that one, and hence also the 0.10.4d release, on Jan 3 / Jan 4).

Instead, today I shall be posting my end-of-year review that, as ever, I’ve been working on gradually across the entire year (since it’s always way too long to write at the last minute!). Overall, it has been a good year! If, sadly, rather challenging in its final quarter due to health stuff. Work-wise, I published a ton of papers on a range of topics, including the first ever research focused on Japanese Twitch streamers and the first ever focused on Australian Twitch streamers, as well as esports in Singapore, artists and gig workers who support Twitch streamers, poker on Twitch, and the role of time and temporality in Twitch streaming. I also finally got back into the big grant game (the BGG, if you will) and submitted some major research funding applications for the first time in many years – so we’ll see whether any of those actually wind up coming through or not. I’ve additionally now wound up taking the lead in my department in the fight against the putrid technology is generative AI, and its destruction of education and learning everywhere (don’t get me started on this one). In my leisure hours, meanwhile, I finally finished reading the Malazan Book of the Fallen, which is an insane masterwork of drama and action and compassion and wit and tragedy, along with soul-crushing horror and soul-lifting courage, and even taking into account the significant parts that didn’t do much for me, it definitely turned out to be a three-year on-and-off reading project which was absolutely worth the time I gave it. It’s a staggering masterpiece, a truly sui generis work, maybe the best thing I’ve ever read (with the Aubrey-Maturin series being the only other realistic competitor for that title), and a huge inspiration for pushing URR’s worldbuilding and world depth and complexity to ever higher levels. I also this year managed my longest ever walks, and my heaviest ever lifts, and it’s really pleasing that despite some health problems I’m still managing to push towards greater health in other areas. In game development, last but certainly not least, I had the most productive and innovative six-months I’ve ever had in game development in the first half of this year. I’ve finally actually developed procedurally–generated riddles for the first time in a game, and doing so in a way that can already yield billions of permutations, and begun their integration into the game proper. I then a pretty good second six months too, focused on bug-fixing and soundtrack development, although developing the player’s quest journal was another huge leap forward (as was everything else it put in place for book generation in the near future), even if this period wasn’t quite as sharp as I would have liked because of the health challenges. I have also applied for a game development grant (!!!) so that’s exciting, and fresh, and weird, as well as commissioning a soundtrack, which is just as exciting, fresh, and weird, in its own way. As I write this now at the end of the year, readying myself for a holiday break, I’m incredibly excited and energised for 2026 and getting 0.11 released, and I can’t wait to get back to it all after a bit of a pause.

Also this year I played fourteen games, which is a little above my usual (10-12) number of games I get through in a given year. One of the great ironies, of course, of being a games researcher and game designer in my spare time is that my time for actually playing games is so significantly reduced compared to my teenage years – even though it’s that very same passion that pushed me down these paths in the first place. Nevertheless, these 14 have, for the most part, been a real joy this year, and I had a lot of fun writing about them.

So, without further ado:

Return of the Obra Dinn

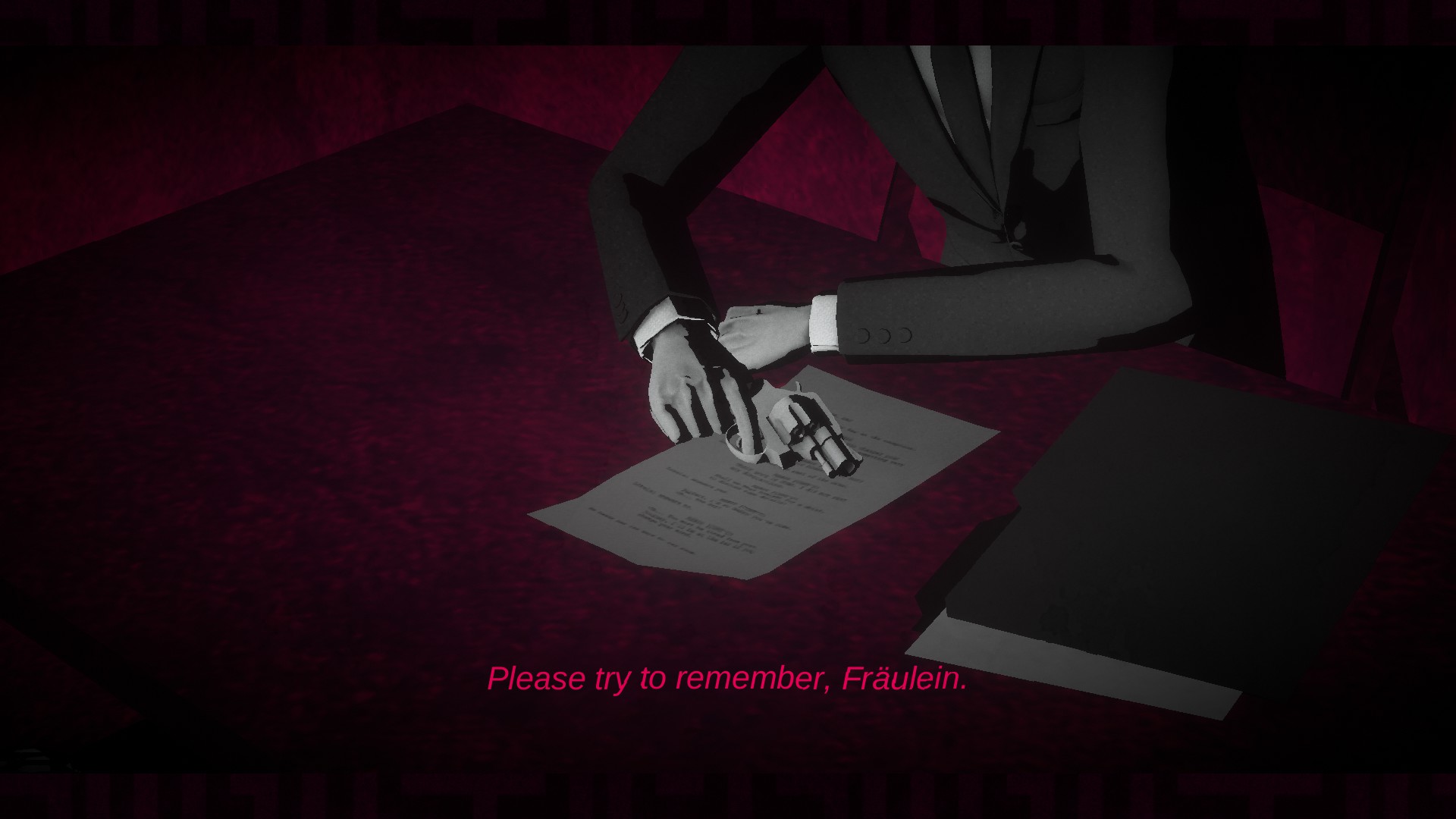

The first game I completed in 2025 was Return of the Obra Dinn. This had long been on my list for obvious reasons – it’s a deduction-focused cryptic-y riddle-y sort of game – but I’d actually held off from it for a while because I was worried the art style would mess with my eyes. Happy it didn’t (the game is honestly pretty visually stunning), and although my time on (and indeed, briefly, off) the Obra Dinn didn’t take up too many days, I really did enjoy it. The game sets you on a sailing vessel of the 1800s and tasks you with using a stopwatch – able to show you the exact moments of someone’s death – to decipher how everyone on the vessel perished, as well as who they are. This generally requires you to input three pieces of information, being someone’s name, how they died, and the name or identity of their killer, if they had one (so “shot with a gun” is insufficient, but “shot with a gun by Joe Bloggs” is enough – if you can work out who the shooter was). As the game progresses we discover that the titular vessel experienced what might politely be called a run of bad luck, with only a handful of survivors and a tremendous volume of corpses. The story has to be pieced together by these death vistas, and without spoiling anything, I loved some of the weird directions the game’s plot wound up going in. It hit my appreciation both for fiction from this period – the Aubrey-Maturin series by Patrick O’Brian is the finest set of novels ever written, and indeed a big inspiration for some world elements of URR – and more speculative fiction as well. There’s also fantastic voice acting which goes along with the death scenes, and these vistas themselves are just beautifully staged, with a real richness and attention to detail. Despite the extraordinary strangeness of the setting, the wider world you find yourself in, and the highly distinctive gameplay, it always feels extremely solid and grounded and present, and this is overall just a very skillfully executed trick.

This attention to detail, indeed, is what you need to actually complete the game. A lot of the information is pretty obvious in the sense that sometimes a person’s name is explicitly used, or perhaps there’s part of the main picture that tells you who someone is. Other times, however, trickier stuff has to be used to make deductions (there are interesting overlaps here with what I talked about earlier this year in terms of classifying different tiers of in-game information in URR according to how obscure it is to locate). Sometimes a person’s accent matters, or a person’s clothing, or even what room they’re going in and out of, or something they’re carrying, or apparently doing, during one of these fatal freeze-frame vistas. The game also allows for some minor guesswork, however, explicitly telling the player that definitive information is rare and thus one must infer from limited data – but people and their fates are only confirmed in groups of three, so one can’t just guess madly. It’s a good system and it works well, though not always – there are, for example, two women passengers on board (and two others who are easy to identify), and the thing that tells them apart is incredibly subtle… but when there are only two options to pick from, they’re easy to brute force. This example stood out to me as one of the game’s few flaws, where the brute force method was so easy for this pair, and the intended method so hard, that little was lost. Outside of that, however, there’s a lot of fun stitching together the information you’re given. As an aside, the music is also wonderful, and incredibly dramatic and fitting and entertaining. I am notoriously aurally ignorant / stunted, but I really enjoyed this part of the work a lot. Like many of the games I enjoy the most, this is a genuinely unique game (though it does of course share some DNA with other cryptic riddle games), and I think it’s an absolute blast.

That poor monkey, though!

Balatro

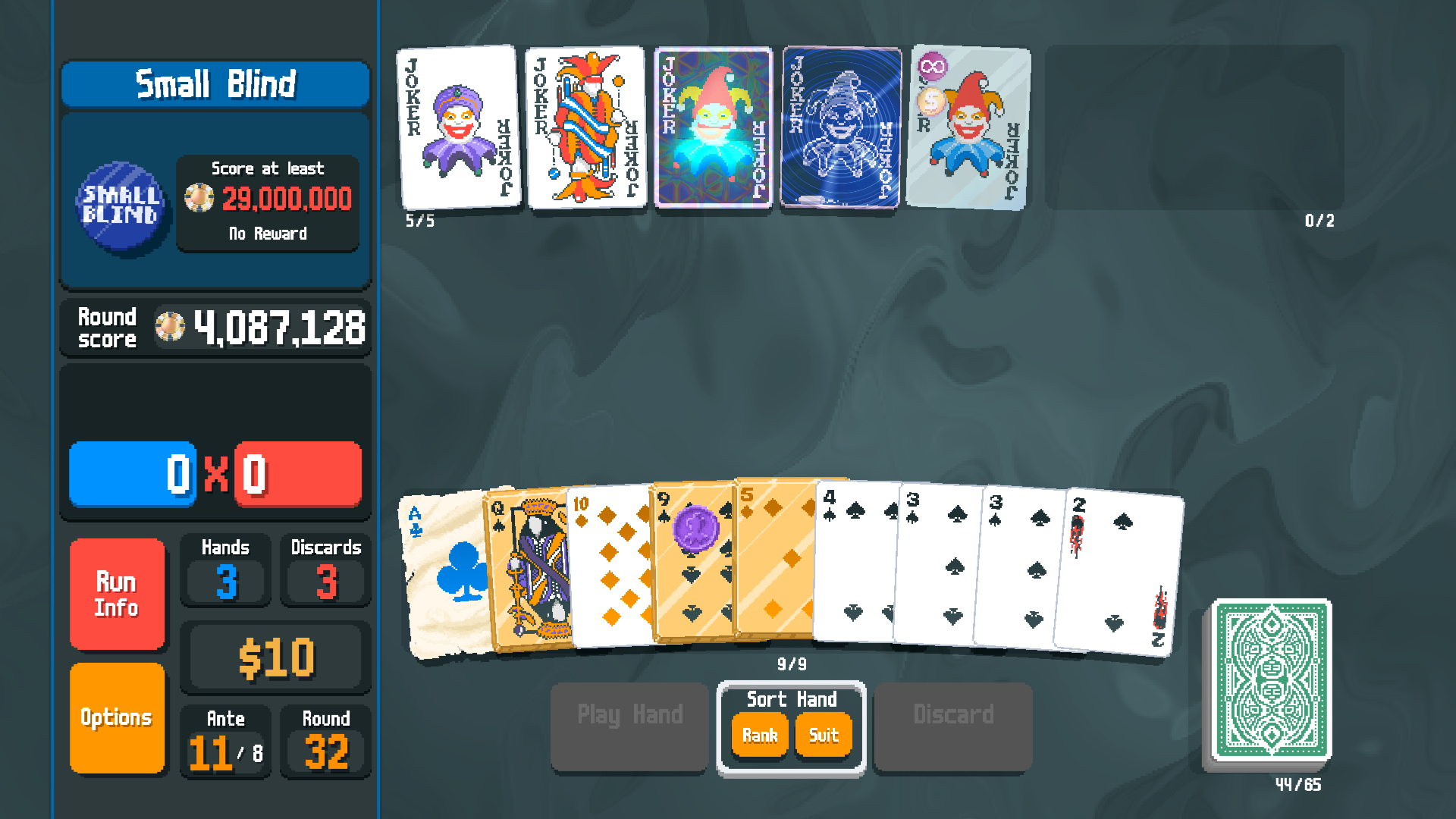

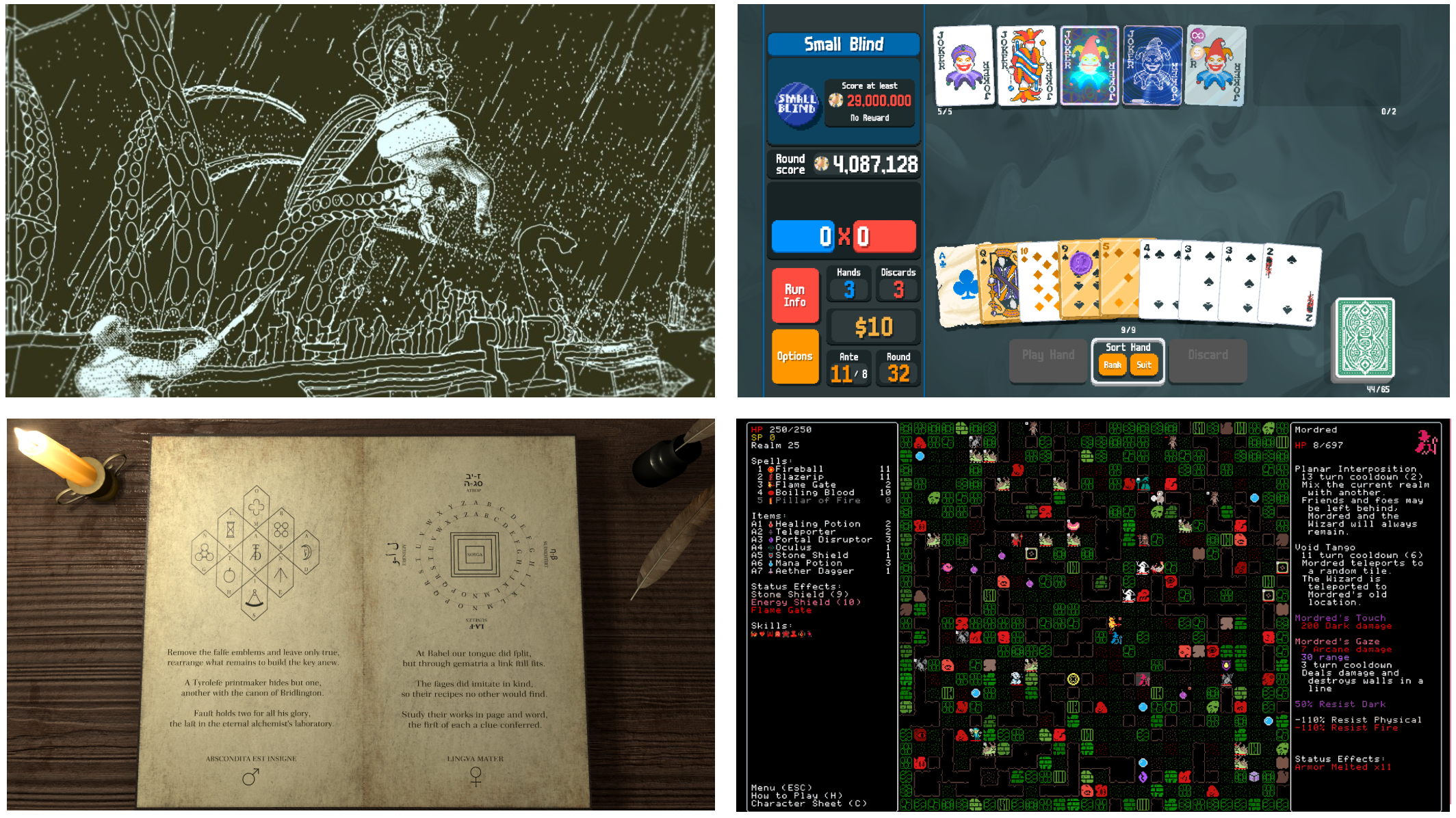

I had an interesting experience with Balatro, friends. I downloaded it, played it, and won with “white stake” (the starting difficulty)… and decided it just wasn’t interesting enough to continue with. I don’t have any interest in incremental games or autobattler games – this was part of the issue I had with Loop Hero from last year – and Balatro seemed to be another one of those. I didn’t really understand what all the hype was about and so I called it a day. That was, however, until I was watching a live stream, and saw the player use the “unlock all” button (which I had not found) to leap straight up to the highest difficulty, which appeared to be different, and so much more demanding, that it might as well have been a different game. I closed the stream, opened Balatro, activated the “gold stake” difficulties on all the decks, and the challenge runs… and suddenly, I found the game. Suddenly Balatro transformed into a game of significant strategy and significant tactical depth – although both far below top-rank roguelite / roguelike-y games – and one with a lot of charm as well. The graphics are gorgeous and it’s clear that a lot of time and energy and attention has been put into them, and as with all good games of this type, there are a tremendous variety of ways to win or advance (although, again, fewer than top RL games). While I found it very satisfying, as ever, to find these interesting combinations and push them through, I did find that a particular run tended to change very little once you got started. In this regard it really stood out, and not in a positive way, from anything from FTL to DCSS to Slay the Spire, since in all those games a build-changing card or artefact or item or whatever can appear in the late game and transform your plans – and I think that speaks to the richness and quality of those games’ designs. Here, though, past even just the first few hands, you pretty much know your build, and you follow it through. Pursuing that kind of min-maxing is satisfying in its own way… but less than other kinds of play, at least for me.

It was also interesting to see elements of the game that didn’t really click with me at all – such as the TCG bit. You can buy cards in packs, and you open those packs, and I’ve seen enough Twitch to know that people really enjoy opening card packs… but I’ve never done that in my life in the real world, so that didn’t really “do” anything for me. Similarly, the speed of the game and its core loop did fly a bit too close to “just one more turn!” game design for me compared to what I normally like – and I even found myself sometimes becoming a little mindless in my play, which ordinarily never happens. Yet on a good run, where one made smart choices, and found interesting combos, there was a great deal of satisfaction to be had (and gosh, that pixel art is great). Ultimately the roguelite, card game, and deckbuilding elements of this game, I really like… but the clicker / incremental, autobattler, and TCG elements, leave me completely cold. The variety of jokers and the play styles they create is impressive (and the pixel art is very charming)… yet so many runs play in such similar ways (even on the highest difficulty), and there is very little tactical depth to your decisions once your build is settled, nor do builds change later in a run and adapt to new developments as they do in most roguelikes and roguelites alike. I’m overall honestly surprised the game has been as successful it has been, which I don’t mean in a derisive way in the least, but rather an admission of a clear gap in my own understanding of the contemporary games market. Have games with vaguely gambling-esque mechanics and aesthetics become this popular this fast? Are games that touch on incremental / clicker and autobattler mechanics now so widely loved? Does everyone else on the planet except me play TCG games, and thus loved all the TCG elements that I didn’t have any real emotional connection to or derive any particular joy from? I have no idea about the answers to any of these questions – but either way, the game’s a winner, even if it must be cranked up to the maximum difficulty immediately in order to be a thoughtful strategic game, instead of a clicker yawnfest. Unlock all, and have fun!

(We also did a Roguelike Radio episode on the game, which you can find here!)

Cube Escape

One of the real highlights for me this year has been enjoying the Cube Escape games, which I’m slowly working through from beginning to end. Each game generally places you inside a “cube”, in the sense that there are four walls and a ceiling you can look at (though never the floor – so far?), and these are essentially point-and-click adventure games where you’re collecting items, collecting information, and then finding the right place to use both of them in order to have some effect on the game world. The first ones were pretty basic but not at all objectionable, though one thing I’ve really enjoyed as my play has continued is the ramping-up of complexity and artistic quality as the games have gone on. Once I was around four or five games in I was really noticing a stark difference in how much was going on, and one of them I did recently – Cube Escape: Birthday – really impressed me on that front with so many puzzles, a much more ambitious framing and narrative, and all kinds of weirdness going on. Indeed, the weirdness is pretty key, since the games draw in their setting and overall feel from Twin Peaks. I’ve never actually seen Twin Peaks – though I do intend to in the near future – but I know enough to know it’s the chief inspiration for these games, and insofar as I understand the Twin Peaks vibe, these games seem to capture it magnificently. In one puzzle one needs to acquire a straight razor and shave one’s beard – the beard hairs then fall into the sink. You then need to turn on the tap, and the beard hairs gather in the plughole. But then, after a moment, they form together, and you realise the beard hairs have come together into a baby crow! Or perhaps in another puzzle, you slice open a fruit, and discover a staircase inside, which you then (somehow) descend – and so on. They are very surreal and very strange indeed, but I’m enjoying this bizarre world, and trying to figure out what is actually going on, a great deal.

The challenge with these sorts of games is always, of course, to prevent the player from succeeding by just random clicking, and instead requiring actual thoughts and decisions that reflect logical choices for how X might go with Y in order to create outcome Z. The first handful of games in the initial collection of nine games could definitely be solved to a large degree by brute-forcing in that manner, and although one tries not to, even as someone who adores riddles and cryptic things in games like this, it can be hard to resist the urge to just click on things until something happens. Quite soon, however, the games moved past this, in part through a growing complexity and detail in their puzzles, in part through a growing complexity and specificity in solutions, and also in part through the growing size of the puzzle worlds, with later games employing larger spaces – while still being “cubes” – that had far more interactive elements in them, and far more steps to complete, thus again reducing the viability of brute-forcing one’s way through. I’m not quite sure how far through the series I am right now, and I’m making sure not to investigate this in order to avoid potential spoilers, but overall I’m really having a blast in them, and a number of the puzzles are genuinely really fresh and interesting in what they expect from the player (although a handful are also bloody annoying, but that’s less common). My one gripe would be the fact that a couple of puzzles that were very hard for me as a non-musical person, and also the couple of jump scares in the initial games. I pay with no sound because I can’t handle aural jump-scares – visual is fine and barely evokes a flicker in me, but aural makes me leap out of my skin, and I don’t need that in my life – so I have no idea what the soundscape of these games are like, but that’s okay. I’m deep into the mystery of what on earth is happening in and around Rusty Lake, and these strange animal-headed people, and I’m keen to finish off all the currently-released ones in the coming year.

Infra Arcana

I’ve thought about playing Infra Arcana for many years, but – I don’t mind admitting – I’ve held off because especially in a game without a Wiki, mastering or even attempting to master a classic roguelike is a serious undertaking of time and effort. Indeed, for me, the joy of classic roguelikes has often been in downloading the information into one’s brain as rapidly as possible, and then using it to master these extraordinarily strategically and tactically complex games. I fully confess that, like many players, I can find a death from ignorance frustrating, whereas a death from my own mistakes is of course entirely fine. This sense has only grown as my life has become busier, and I find myself with less time to commit to classic roguelike games, and their potentially lengthy playthroughs, than I once did. This might be surprising to people reading who know my affection for cryptic riddle games, given that those games are all about the player’s ignorance, and about spending huge amounts of time trying to overcome that ignorance. Why do I hugely enjoy the latter, and yet sometimes prefer to play roguelikes with Wikis, in the case of the former? I couldn’t say – but the point is that Infra Arcana seemed to me “NetHack or DCSS without a Wiki”, and that’s a rather intimidating prospect for any sane person. Yet I decided this was the year to give it a shot because I’d heard so many very good things about it, the game often described as unusually challenging, having a great atmosphere, some novel gameplay mechanics, and an incredibly good evoking of the overall Lovecraftian or cosmic horror feeling. I also just really wanted a proper, difficult, long-term roguelike to properly sink my teeth into, potentially for several years (my days of spending a day downloading the NetHack wiki into my brain and then grinding out a win within a week in a fit of obsessive focus that only an undergraduate could manage are long over), and this seemed the one to go with. Although it took me a minute to really get into it and become familiar with the controls, so far my best run so far has taken me to the 31st floor, which is the final boss floor (I was not successful in challenging him…) and I am enjoying the game tremendously.

The reviews and commentary I’ve read, however, were certainly not kidding when they described how very unyielding, and dangerous, the game is – again, reminding me very much of NetHack. Discretion is certainly often the better part of valour, and I’ve had to again get used to the rogue aspect of the roguelike, avoiding combat whenever possible (even with a strong combat class in some cases) and thinking seriously about the layouts of the levels, other ways to get to places I want to access, and the optimal times to use the very limited resources we have in this game. I began as the “War Veteran” class which is the most directly combat-focused class, with an emphasis both on melee and ranged combat, but I soon found I was really struggling to successfully push into the mid-game as a result of the character finding it hard to heal in major combats, and relying too much on ranged attacks which of course have limited ammunition. Four of the other five classes felt more advanced to me, but the “Ghoul” class (or indeed, species / race / creature / ???) felt more promising, and I’ve had far more success here, consistently getting good runs going as a result of the excellent melee abilities of the class, ability to heal in combat, ability to heal by eating corpses, and “frenzy” ability. This has now definitely settled into my brain as one of the games I play while taking breaks from work – e.g. I do a bunch of work then do a single floor of IF, and then repeat – and games in that category are always both a really fun break, and a big help when dealing with less exciting elements of one’s job or other life commitments. More generally I think the game’s Lovecraftian feel is really outstanding in visuals, game design and sound design, and a lot of the game’s potions and spells have genuinely interesting effects; equally the historical setting allows for some interesting weapons, and the “science fiction” aspects of Lovecraft’s work enable for a very fresh and interesting blending of the supernatural and the scientific in very cool ways. Overall I’m really impressed by the tightness of the design and the challenges the game is able to pose even a very experienced classic roguelike ascender such as myself, and I definitely expect to keep playing into 2026!

Halo 3

Halo was one of the defining games of my teenage years – thousands of hours of online play, and dozens upon dozens of hours at LAN parties. Fancying a bit of a return to old glories, I heard that the Halo 3 playlists on the main Steam Halo release had a good number of players, so I decided to check it out. I played it for a little bit, and sometimes had a good time reliving those great old times, but much of my enjoyment was ruined by the ludicrous banning rules. On my third ever game my connection dropped… and I was then banned from matchmaking for a while?! I found myself just staring at the screen in disbelief after this happened, after which I just started laughing at the absurdity of the situation. The early Halo games were notorious for doing absolutely nothing to ban cheaters – much to the intense and teenaged nerd rage of many competitive players who conducted themselves appropriately, including myself – and so I actually found myself laughing out loud at having been temporarily banned for a dropped connection. And then once the ban was lifted, I was told I’d been banned a second time… for betraying teammates!? Gosh, that’s a fascinating hypothesis Halo 3 – tell me, did this happen before, or after, I was kicked out of matchmaking for cheating the first time? Given the extreme loathing of cheaters I evinced during my teenage years, the irony of this is extreme, and was not lost on me. Even more wonderfully, there was one time in a later game when I did – accidentally – genuinely betray a teammate, albeit with no intention to do so, and the game – guess what? – naturally didn’t care in the least! What an intensely, intensely idiotic piece of software. And then, after that, I got matched in an objective game with two clowns who immediately quit, and so I quit as well because there was no point in fighting on – and then, of course, I got punished by the game for that too!

Ultimately the whole thing just became a comedy of errors spawned by a too-small pool of potential players, ridiculous banning systems, and a game design which apparently thinks people have infinite time to waste in games guaranteed to be a loss. Maybe I did as a teenager (indeed, I quite enjoyed fighting a rearguard action, and making the other team earn the victory), but I don’t any more – give me a close match, or don’t waste my time. Yet this temporary banning lunacy wasn’t the only thing that damaged my fun with the game. I also increasingly recognised how much of the fun of Halo had always come from my teammates, being one close friend in Halo 1, a team of five or six very skilled friends in Halo 2 and 3… and without them, it’s an entertaining distraction that might help me through a tedious job, and sometimes has those wonderful moments of high skill that are so satisfying, but also lacks that long-term appeal. There’s no creation of shared memories, and shared victories. There’s no sense of contribution to a team, to a greater whole, and nothing bonding a social group even more closely together. There’s still a thrill in mastery and good tactical and strategic decision-making, but gosh, how I miss playing the game with my friends. There was such wonderful shared fun, an incredibly active competitive ladder where games appeared every two seconds instead of sometimes waiting for multiple minutes at a time, and a banning system which – while it allowed in every cheater under the sun – at least didn’t ban those of us just trying to play. Thus, as a reliving of one’s personal history, Halo 3 was briefly fun, but incomplete, and I’ll just be sticking to my fond memories from this point on. I enjoyed and relished the ebb and flow of the competitive play… yet missed battling alongside my teammates and the shared whoops of joy, the tense moments in a deathmatch at a score of 49-49, the commiserations, the hilarious insults slung over voice chat.

Ah well – as they say in Casablanca, we’ll always have the LAN parties.

The Murder of Sonic the Hedgehog

In my childhood years I adored the early Sonic The Hedgehog games – Sonic 1, Sonic 2, Sonic 3, Sonic & Knuckles, and also Sonic CD, even if I really didn’t understand the time travel mechanics when I was 6. I loved the gameplay, I loved the graphics, I loved the secrets, and already at a young age the games’ fundamental thematic conflict of “nature and animals” vs “industry and machines” spoke to me, even at a moment when I was only just starting to get an initial degree of environmental consciousness / morality. I read all the comics, watched all the television series, and in my early years was wholly captivated by the exciting antics of the wise-cracking blue rodent. However, I think we can all agree that the last thirty or so Sonic games have, er… not been great. They’ve not been great, friends. At their worst, Sonic’s developers have descended into releasing games which are quite literally unfinished and not ready to release (yet out the door they go anyway!), and even at their best, they’re weird, indecipherable gibberish, with painful gameplay, soulless graphics and visual direction, and a quality of writing and voice acting that are embarrassing. There’s a reason why modern Sonic games are, alas, essentially a meme in their own right. Yet although I deride the last few dozen Sonic games utterly, there remains a sadness in my heart for the loss of a visually arresting, charming, and exciting platformer series, which once meant a great deal to me. This is one of the reasons why the recent classic-styled Sonic Mania was a real joy – as I reviewed a couple of years ago – and indeed I’m keeping an eye on some quite promising mods for the classic games, which look like they might be rather compelling once finished. However, this year I came across The Murder of Sonic the Hedgehog, a detective / clue-solving mystery game. Whilst we can all agree that poor Sonic’s actual murder has been committed by the brain-clotted numbskulls and flappy-shoed clowns at SEGA over the past few decades, this particular game turned out to be an absolute delight.

TMOSTH wasn’t a long playthrough, but I genuinely enjoyed every moment of it (this is only my second ever visual novel, after Doki Doki Literature Club a few years ago). The game sets you on a train during a murder mystery party for Sonic’s birthday, but – gasp! – it appears that all is not as it seems! The detective elements are not overly challenging (although I didn’t expect them to be) but still require at least a modicum of thought and attention, but the real pleasure is in the setting and the quality of the writing and the art, both of which are absolutely first-rate. Indeed, the game genuinely made me laugh at quite a few points (Espio’s poetry, the heist plan on the whiteboard, etc), and even when it didn’t elicit a laugh-out-loud moment, a lot of the dialogue made me smile, and delivers a lot of small one-liners and amusing little responses. It’s heartfelt, and charming, and shows so much care and attention, being thus so unlike how the recent Sonic games have been actively tiresome, charmless, and paint-by-numbers. One surprising element was a mini-game reminiscent of some of the bonus rounds from classic Sonic games which triggers whenever your character is trying to make a deduction. It certainly isn’t the hardest thing I’ve ever played, yet nor is it wholly trivial, ramping up in difficulty surprisingly fast for something that bills itself as a visual novel – I wasn’t surprised to discover, later, that its difficulty can be toned down in the main menu. I finished the game with a real sense of warmth and a real grin on my face, just charmed by the game’s visuals, its writing, its attention to detail, and the sense of delight and humour the whole thing exuded. I recommend it highly, especially for those who remember the classic Sonic games with affection.

Alchemia

Now this is an interesting game. The entire “game”, in the sense of the software you download, is just a book containing around a dozen pages and a front and back cover. Its interior content is extraordinarily cryptic, however, and the goal is to use the internet – and not just Google / Wikipedia, as you’re likely to end up on some far more obscure places too – to decipher what is meant by each page, and thus how to “solve” or “win” the game. I’d had my eye on this for a while as I’m always on the lookout for the next ridiculously hard riddle game, and the simplicity of the game’s “mechanics” – while just a glance at the pages immediately suggests how difficult and opaque they’re going to be – really drew me in. I decided to give it a shot, and for the first dozen or so hours I had an absolute blast, solving a couple of pages and making what I thought was decent progress on the other ones. As Noita has previously showed (and indeed, the TV series “Dark”, to a lesser extent), the strange arcana of historical alchemy offers an astonishingly creatively and evocatively rich terrain to do all manner of strange things and explore all manner of strange ideas. Overall I found the solving experience a joy, even if a few parts didn’t make complete sense, there were a few bits I accidentally brute-forced because it was hard to avoid while thinking deeply about the puzzle, and there were some other issues as well. Each page is largely a self-contained puzzle, and I can say that page 4’s puzzle I loved; page 5 was good but some ambiguous elements were present; page 6 I loved; page 7 I loved; page 8 I mostly really liked but one element eluded me (in the end I brute-forced it), yet having even looked at the solution, I don’t understand the source of the answer and it seems wildly, ludicrously more opaque than every other bit of that page; page 9 was the weakest because it contained so many ambiguities that led to potentially “valid” solutions just spiraling in number; page 10 I loved (even if one part is pretty ambiguous and offers multiple logical answers); and the end-game puzzles, combining things from many pages, I loved.

This trap, however, of mistaking something being ambiguous (i.e. possessing many equally logical interpretations but only one is correct) for something being cryptic (i.e. possessing only one totally valid interpretation which is the correct one), sadly led to the weaker parts of the game. Some of the fonts used (particularly the one for Hebrew numbers) were genuinely unclear and that led to many possible interpretations of certain things, while other puzzles had clues that had multiple potential answers, which then had to be fed into other things, and thus one had to do many other steps contingent on those early steps before being able to know which is the correct interpretation of a certain clue earlier in the chain. These long chains of sequential deductions from unclear language with no way to check one’s working (which quickly can spiral to dozens or more possibilities that seem to equally well fulfil the clue’s instructions) were damned frustrating. One extreme example would be the second and third stanzas on page 9, which I would propose have around a dozen possible and utterly reasonable interpretations, but take so much effort to test out. Coupled with, as I say, a lack of visual clarity in a few places, and by a few clues that are perhaps a little iffy, there was some real frustration here. I nevertheless applaud Alchemia with all I have for its wild ambition and confidence in the player – the parts that flowed smoothly I truly adored (i.e. solutions and pathways that were cryptic but never ambiguous) – but the parts that were just too vague to make headway in without a lot of trial and error quickly made me sour on the whole thing. Perhaps fifteen years ago I would have been less frustrated by this, but I don’t have time to create and then check two dozen ciphertexts I’ve been able to put together, all of which seem to fulfil the instructions equally well, to see which is the correct one and which twenty-three are incorrect (despite being entirely reasonable interpretations of the clues). A follow-up to this game, heeding some of these lessons from other cryptic riddles games – be cryptic, but never ambiguous, in all ways (clues, visuals, language use) – would be something incredible, and something I’d be hugely excited to play.

Snakebird

I am not someone who rages at games (being not being thirteen years old) but the only game in the last decade that has elicited any genuine frustration from me was The Witness. I strongly disliked it when I played it in 2020 due to how little it values the player’s time. My frustrations at the thing have only continued to grow over the years, and these frustrations I have carefully nurtured and cared for deep within my soul as time has gone by, like a festering wound. Why would a game give you a really compelling type of puzzle to explore, and then actively prevent you from doing more of them? Absolutely unhinged game design. I’m indeed looking forward to playing The Looker at some point soon, which I understand to essentially be a parody of the other game in question, and I will be interested to see whether its critiques and snarks align with mine. However, Snakebird, by contrast, is the soothing salve to everything that game does wrong. It has a really nice core puzzle type and gives the player nothing, absolutely nothing, except a lovely stream of progressively more complex puzzles. Snakebird puts you in control of the titular creature, who is a very endearing wiggly thing that grows one tile longer with each fruit you consume (the inspiration of the original “Snake” games of course comes through here). However, unlike in those classic games, your snakebird possesses weight and the game world possesses gravity (i.e. one is looking on the side, rather than looking down from above, as in the classic equivalents). The snakebird can cling to any surface directly beneath it, no matter how far extended out into the open air its body might be, as long as one of its body parts is touching a surface. When nothing has a surface underneath it, however, the snakebird will fall. There are some really tricky little puzzles here, requiring a lot of precision, and taking full advantage of the unusual capabilities of this creature.

Yet past a certain point I found myself becoming gradually more frustrated with some of the puzzles, and simply their extreme difficulty curve (curve? It’s a cliff, a mountain, a space elevator). Many of the later puzzles become unbelievably hard with extraordinary rapidity, and while the game does prepare you for the mechanics, it still comes as a hell of a shock. As someone who rates La-Mulana as amongst the greatest games ever made, this is not exactly a sensation I’m unfamiliar with, or I expected… and yet this game did make me feel that. Although I went back to it throughout the year, and did continue to make progress (as I write this only two or three of the game’s fifty-ish levels are incomplete), and did enjoy some of those moments of realisation and discovery that the game mechanics I already knew could be used or deployed in some clever and other ways… I do think the later half of the levels are sometimes just too hard to be all that satisfying or fun. This is especially because one is often looking for such a niche solution, such a precise answer, and everything other than that “eureka!” moments isn’t really moving one much further along. I found a thread on Reddit that described it as “lockpicking” instead of “puzzle solving”, and this is not a bad metaphor at all. This also points me towards something perhaps quite subtle in puzzle design which I hadn’t thought of until now – the value of interim stages, the value of feeling like progress has been made, even if a solution hasn’t yet been attained (see also my thoughts on Alchemia). Given the nature of the puzzles I’m generating in URR I don’t anticipate this being at all a problem there, since in many cases you will be able to figure out some parts before other parts, but it’s still something interesting to keep in mind. Anyway, I have enjoyed Snakebird – it brings lovely visuals, nice soothing music, and some absolutely fiendish puzzles, even if it’s hard to not feel that some are perhaps just a little too fiendish, or too specific, or too exacting, for their own good…?

Edit (24/01/2026): having now completed those final few levels, I think I was slightly too harsh on some of the later levels! Some of these levels are incredibly intimidating, but actually once one gets going and gets the sense of what you should be doing, they do unfurl themselves quite nicely. While the puzzles are very lockpick-y, I no longer feel quite as negative about this as I did before – probably at least in part because of the very last level of the whole game which was just so, so elegant, in its lockpicking. So I partly rescind my grumbling here.

Cryptic Crosswords

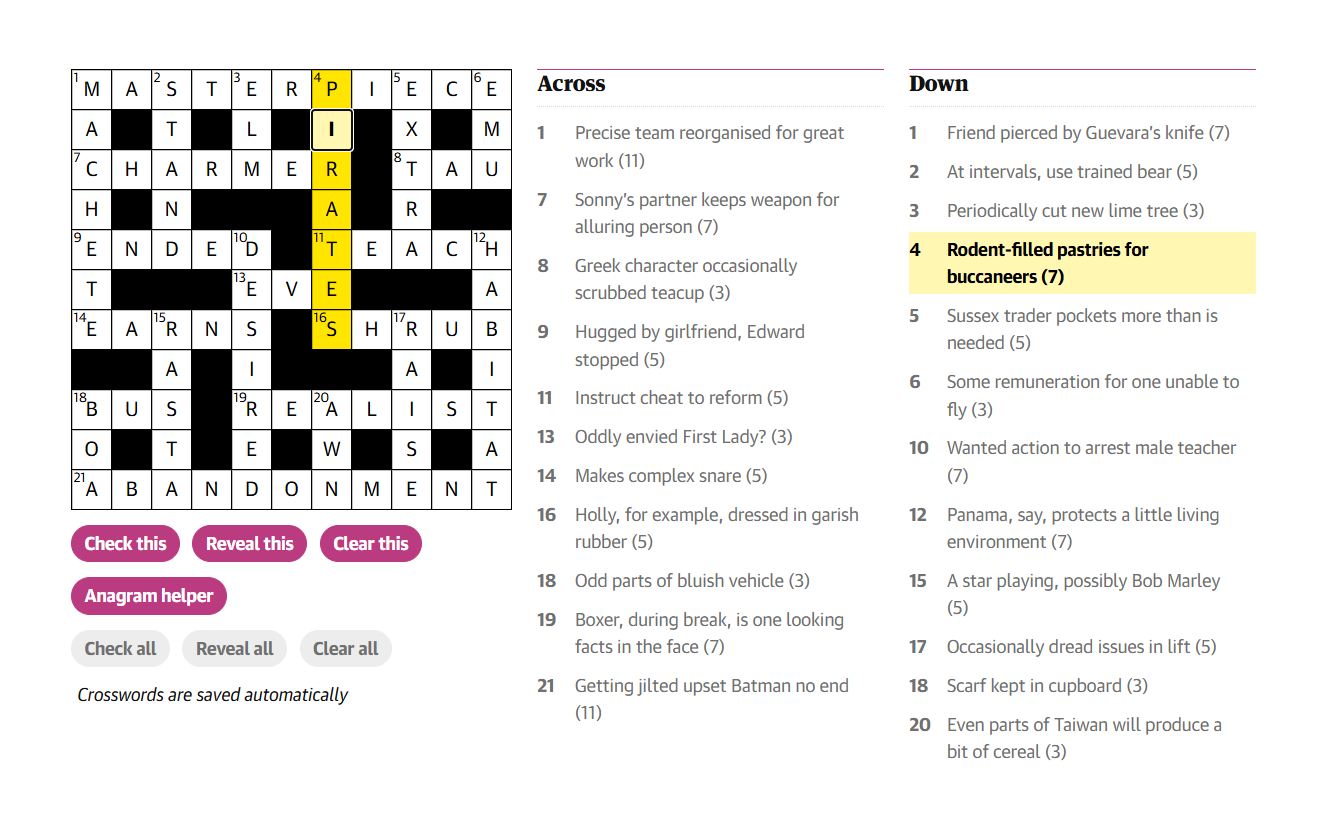

I have long been an avid enjoyer of traditional crosswords, mostly those in the Guardian, though I’ve also on occasion enjoyed the New York Times ones (even if the required knowledge of peculiar Americana often exceeds my own). In my late teen and early adult years I briefly tried cryptic crosswords, and was very pleased with myself when I was able to decipher an anagrammatic clue, and equally pleased when I could understand – after seeing the answer – why the answer was the answer, even if the process of getting the answer seemed ludicrously difficult. However, in January of this year I decided to take the plunge, specifically as a result of the Guardian’s new “quick cryptic” crosswords, which have been specifically designed to ease the new cryptic crossworder solver into the conventions and the types of clues that one might expect to find. Each of these helpfully explains that the clues can only be one of four “types” – such as an anagram, or a hidden word within the clue, and so on – and then all clues within that puzzle must adhere to those specifications. With these pieces in mind, and the extra thing these crosswords kindly give you (that a traditional crossword clue is also hidden within the wider clue), cryptic crosswords are promptly transformed from the most bizarre, baffling, and inaccessible form of puzzle, into actually… something one can do! And not just something one can do, but something that’s really very fun to do, and a really rewarding and satisfying mental challenge. It’s really gratifying to find one’s way through the maze in a clue to understand exactly what it’s getting at, and to start to spot some of the hints and signifiers about what type of clue it might be. Without that kind of guidance and without the experience of seeing the important parts of a clue, cryptic crosswords really are tremendously inaccessible things, and so I have to give full credit to this series for doing a fantastic job of easing me into the style.

At time of writing I’ve done a good number of the quick cryptics the Guardian offers and I’ve really got a huge amount of pleasure out of them. One of the real joys is in the transformation from something seemingly impossible, into something possible – this is of course something that I seek generally in games, whether it’s a roguelike or a cryptic riddle game, and I’m certainly getting the same experience here. Cryptic crosswords seem so stunningly inaccessible until one actually understands the principles that they run by, and until one begins to develop the ability to see the parts of the clue that are important, the parts that are just chaff, and hence how one might deduce meaning from such bizarre sentences. Again, the experience here is very similar to both of my favourite genres of digital game. In roguelikes the possibility of success can seem to the inexperienced player utterly dependent on luck until one begins to see the subtleties, the ways that your resources can be used more effectively, the small optimisations that can improve your chances of success, the strategic choices that play out much later in the game, and so on. Not seeing these, of course, is why so many players continue to post on roguelike forums and the roguelike Discord about how FTL and Slay the Spire, even on Easy or Ascension 1, are games of pure luck! I always have to hold my tongue when I see those (though I confess it gets harder with each passing year, somehow – I feel roguelike and roguelite games are now so popular and so discussed and so played, how can anyone seriously still think these are games of luck??). Equally, there’s so much in the cryptic crossword that echoes the cryptic riddle game as well, with those games pushing the player to notice things that might seem unimportant, or trivial, or easily overlooked, such as a piece of background that looks perhaps different in some way, or some bit of flavour text which might be in fact far more than flavour text, and so on. Getting the same experience here in cryptic crosswords has been super fun, and now that I’m better at seeing the pieces of the clue than I was before, I’m excited to keep playing with these into the coming year. I don’t yet feel ready to “graduate” from the quick cryptics – but I’m making progress.

MoonQuest

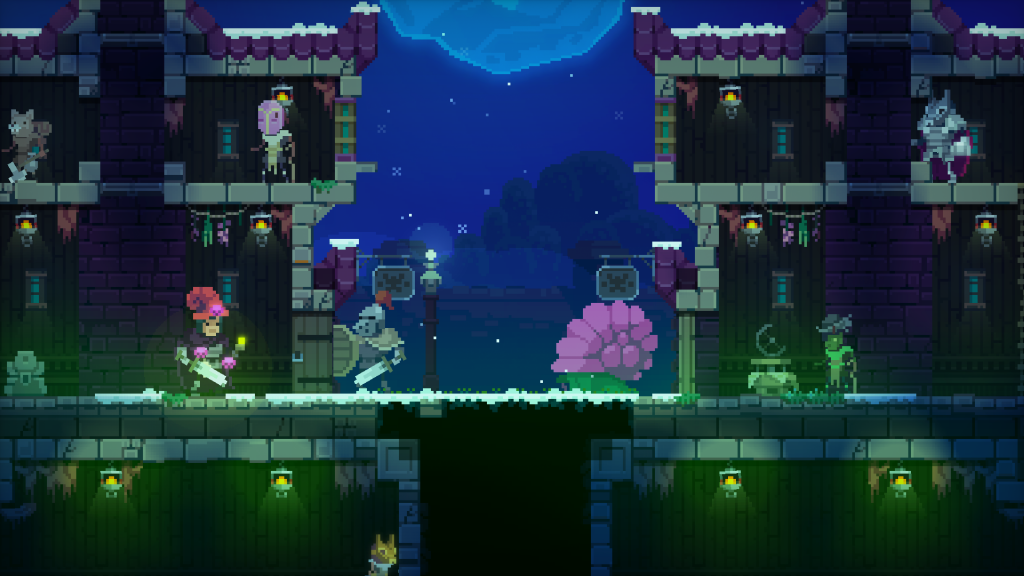

It’s hard to say when I first became aware of MoonQuest, though it must have been many many years ago now, since it was a long-term one-person PCG-heavy project, and there just aren’t that many of those out there. I also had a lovely coffee and chat one day with Ben Porter, its developer, many moons ago – I think when I first moved to Australia in 2019 and was in Melbourne for a conference, before the plague hit? Either way, this was one I have been keeping an eye on for ages, and this year I gave it a shot. Here you explore a world that is aesthetically absolutely beautiful, with a real warmth and charm to it. In particular the emphasis on animals really clicked for me, such as the giant snails you can communicate with, and lots of the other creatures – both real-world and imagined – that populate this space. I’m not a huge fan of killing animals in games (indeed, once URR has wildlife, they will likely be unkillable even once combat is implemented, which I know is an unusual approach, but I stand by it) and I appreciate the care and beauty with which the game’s creatures are depicted here, as well as the fact that it’s only really the obviously “enemy” monsters or creatures that need to be dispatched, rather than just wildlife in general. There are also plenty of strange places to visit and plenty of unusual NPCs to meet and trade with and from time to time have a brief chat with, and there’s a really striking and impressive number of items and resources you can acquire. The world map’s overall layout is, as I understand it, generated as well as the particular areas, and I really appreciate this element as well – I’ve always thought it would be interesting to have a Metroidvania game with a generated world layout, and while MoonQuest is not a Metroidvania, I appreciate the large-scale world generation alongside the small-scale world generation being both present, and important. The game is also very mysterious, and it’s not at all clear what your objectives are or how to achieve them, which I often really enjoy as well, and so it ticked that box for me too.

Although a full playthrough is quite short, I really enjoyed the time I spent with it – aside from trying to hunt down one door that seemed (perhaps I was incompetent here?) so well hidden that I actually abandoned locating the blasted thing several times, until I reloaded several more times, each time certain it must be there, it couldn’t be a generation bug, it had to be there, even if I hadn’t yet found it. The combat is relatively simple but enjoyable, especially when facing more dangerous foes that demand some thought in your placement and approach, and the world is wildly charming. However, a core part of the game involves crafting and building and things of this sort, and generally those sorts of mechanics leave me completely cold. Don’t Starve – reviewed twice in previous years, here and here – is a rare exception to that rule, but overall these sorts of things just really don’t do it for me. I’ve consequently seen the game compared to Terraria, and while haven’t played Terraria, I’ve seen screenshots and a couple of videos, and honestly, it’s not the game that MoonQuest evokes for me. Instead, my own playthrough felt slightly more like something such as Noita, or Rain World, a strange and puzzling world whose rules I need to understand and divine. It also has that rare gift of being a world that’s pleasant to just spend time in, without necessarily needing to do anything specific or particularly instrumental or useful with one’s time. I tend not to play games of that type by design, but I do enjoy them. Overall, then, some bits really clicked for me – the Fez-like graphics, the Noita-like strangeness, the Rain-World-like need to decipher the world – and other parts didn’t, i.e. the mining and crafting parts which unfortunately don’t do it for me in something like Minecraft sadly leave me in the same state in other games (visually lovely though MoonQuest is). It’s an unusual little piece, but has a ton of charm and freshness to it, and is absolutely worth a look for those who enjoy these kinds of games.

Paquerette Down the Bunburrows

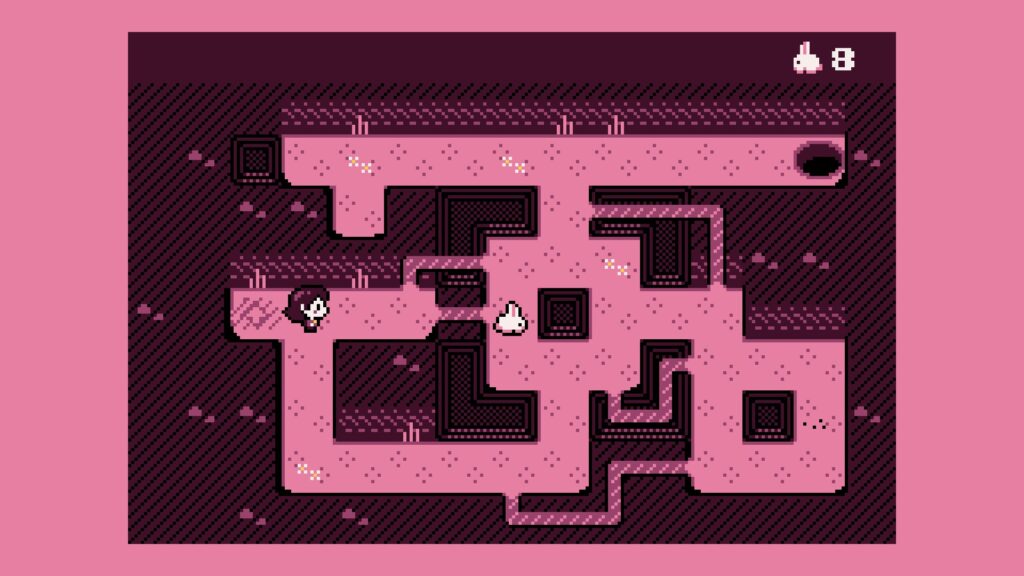

I’d seen this game in quite a few discussions online before I played it – both in lists / forum threads about interesting indie puzzle games to try, but also of games which have many hidden layers, and lots of weird and interesting end-game stuff, and far more mechanics than you initially think are there when you start playing – and all of these things of course appeal to me. I really enjoyed the start of my time with this game, where you go around trying to catch rabbits who move in deterministic and very simple, but still quite tricky and elusive, ways. The early levels were a lot of fun and it was always clear how one had cornered the “bun” in question, and why other approaches or techniques had been unfortunately unsuccessful. The graphics are charming, the music is catchy, and the overall framing of the game is very endearing. Sadly for me, however, that’s about where the success with this game ended. I soon ran into two issues with it, and after another few hours of trying to overcome those, I haven’t gone back. The first issue was the visuals – it was starting to really, really, hurt my eyes. I’ve had minor issues of this sort for years now and I know what causes them: it’s basically straining too hard at a screen to see what the hell’s going on. As long as I don’t strain, I can comfortably do a full day of screen work (with the usual breaks etc, of course), but once I start straining, things start going wrong. Something about the combination of the extreme precision required, alongside the very small tunnels and small details visible in the game world, and the relatively low-contrast visuals (e.g. dark pink against light pink as above, or the dark blue against light blue area was especially bad), all combined to make this game just bloody hard for me to look at. I tried taking breaks, adjusting my position, all the usual stuff, but I just couldn’t stop myself straining to actually make out what was going on screen – and this was a killer blow for my enjoyment of the bunburrows, alas.

Yet even if this hadn’t been true… I’m not sure I would have kept playing, and there’s another reason for that. The problem is that all the levels look extremely similar, since there’s a very finite number of tiles that are used on all the levels, and all those tiles themselves look very similar, and so I found myself quickly not becoming excited when I moved onto the next stage. I might just complete a stage with some open areas and some of the burrows / tubes / runs / whatever the narrow parts are called that only the rabbits can go down, and then I’d reach a new level… also with loads of open areas and loads of burrows / whatever. And the next level. And the next level. And the next one, too, and the dozen or even hundred after that. The levels thus quickly blurred in my mind and I was struggling to get a real sense of distinctiveness from these stages, or a sense that this stage was offering something exciting and interesting which the previous ones didn’t. There’s a sharp disjuncture here with a game like Cube Escape, actually, although a much fairer comparison is something like Chip’s Challenge, since that’s also about moving on a grid and sometimes interacting with other creatures in that grid as well. Each level in CC has a real sense of place which emerges primarily from the aesthetics, and from the combination of puzzle elements which are in that level but not in the other levels. Here, by contrast, nowhere really felt like anywhere, and everywhere just felt like everywhere else. I just didn’t have the motivation to keep slogging through them, unfortunately, as charming as both the aesthetics (eye-strain aside) and concept were. I thus wound up calling it a day after around a half-dozen hours, appreciating the game’s novelty and the simplicity of its core mechanics, as well as its ability to reveal new depths and surprising higher-level puzzles as you go on, but the visuals and the gameplay were ultimately just not for me.

Rift Wizard

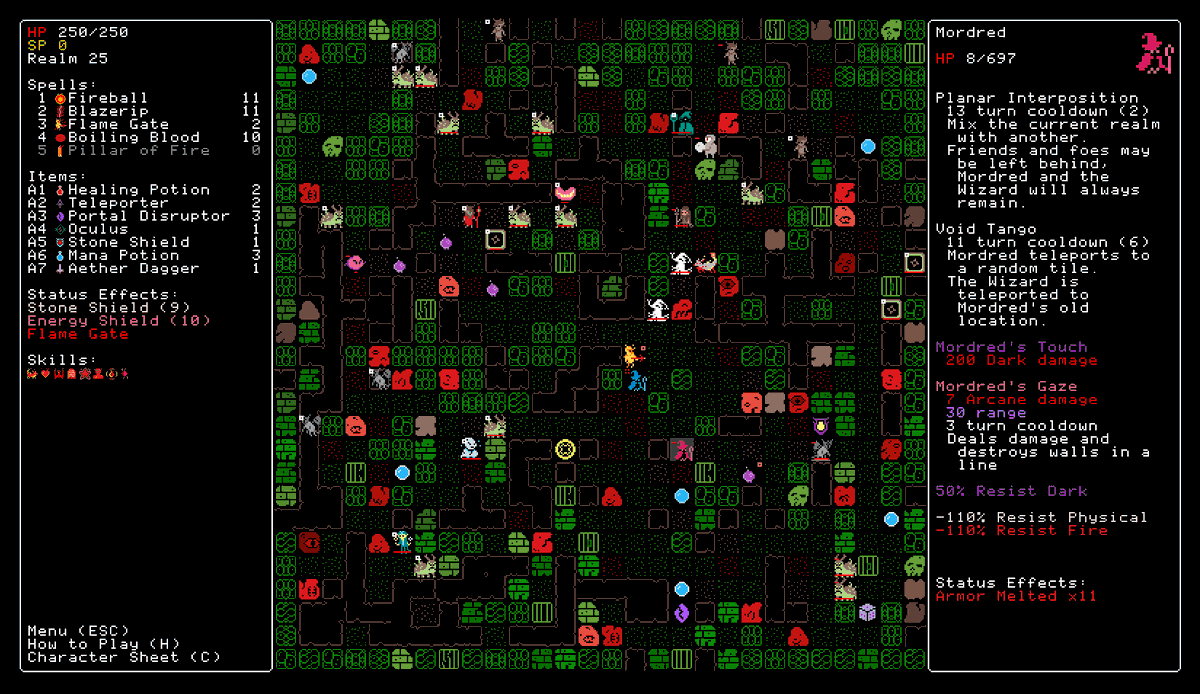

On my list for a long time, I decided this year was the year to try Rift Wizard. This game casts you as a wizard (!) who goes through these things called rifts (!!) filled with vile creatures of many types and with many powers, and your goal is to construct a character capable of surviving twenty-four of them, and then dealing with the final boss. My first attempt ended in disaster because I didn’t have much of a clue what I was doing and I really wasn’t paying enough attention, but my second attempt took me to the final boss. When I arrived at Mordred the first time I managed to give him a decent run for his money – taking two of his five lives – but I had few items remaining that could help, he countered my exact build reasonably well, and I really hadn’t taken a part through the early levels that was anything approaching optimal. His ability to change the map and get rid of your summons was crippling, I lacked much direct damage, and I had no way to follow him around (or at least get back in range) each time he teleported. Once I knew what I was doing, however, my third playthrough – screenshot above – yielded victory, and with a lot of resources to spare, too! The major difference came partly just from a greater understanding of which rifts to take and which to overlook earlier in the game, of course, but it also came partly from knowing exactly what Mordred was going to do, and thus what I would have to counter. In the process, I noticed that my first three runs of Rift Wizard mirrored my first three on FTL (a decade or so ago) exactly! First run is just about understanding what’s going on; second run gets to the final boss, but I die; third run is a first victory. In the process I came to really love the game’s graphics, the complexity and detail of some of its mechanics, and just how interesting the spells – and especially their combinations – really are. Even with that first win, though, and one I enjoyed a lot, the game was far from finished, and I’ve had some fun attempting other builds…

…yet not, perhaps, as much as I anticipated? I was very pleased with getting a second win soon after with a focus on lightning and chaos magic instead of fire and summons, but once that was done… I found myself without much inclination to keep going and get more victories. I looked at the challenge modes, but rather like half of the challenge run options in Balatro, they felt more like things I’d find frustrating than things I’d find challenging. As an aside, I acknowledge here that I think it is difficult to design “good” challenge runs and this is certainly not intended as snark of a game I genuinely enjoyed, but few of the ones listed here really grabbed my attention, and so I found myself disinclined to pursue them. I did dabble a little bit in trying a few other builds but quickly found that I just wasn’t really in the mood to keep going, to keep playing, to push it a little bit further and see what else I could construct. This is pretty rare and unusual for me in any roguelike or roguelite game, as it’s far more normal for me to want to go back and push my skill in the game further by moving to higher difficulties, or a higher class or race or whatever it might be, but in Rift Wizard I confess I found I just didn’t have the inclination. I will be trying out the sequel though, absolutely, both because I really did enjoy my time with this one (even if it was shorter than anticipated), and because it’s important to support other roguelike developers, and maybe that one will click with me for long-term play a little more fully! The Rift Wizard soundtrack is also, as an aside, another inspiration for some elements of the URR soundtrack I’m going for, since it has a lot of very interesting sounds and aesthetics that emphasise the slightly weird and the slightly unsettling, and so quite a few of the references I have sent Nik have in fact been from this game (and the sequel as well, which I haven’t played yet). Anyway, if by some strange coincidence you, too, enjoy a good roguelike (!), this game is a really good time, and maybe you’ll find more longevity there can I did!

The Double Award Winners of 2025

We come now to this year’s winners–

Yes, winners! Plural!

“What’s this?”, I hear you cry, justifiably outraged! “Two games?” – has Mark lost his mind? He has not, and I know that I’ve normally had a single clear winner for a year’s gaming, this year I just can’t pin it down to a single one. I recognise such a move will be controversial and indeed perhaps damnable, yet there’s just no other option. As such, as Chairperson of the MRJ Games Award Committee, I have decreed that it is acceptable to have two joint winners in a given year, and having passed this bold proposal onto the Executive Board of the MRJ Games Award Committee (membership = 1) for consideration and hopeful ratification, they have in turn passed it unanimously, while also quite rightly complimenting the submission for its quality of ideas, its clarity of prose, and its empirical and logical rigour. I really just can’t pick between this year’s winners, friends, and it’s very telling that one is a cryptic riddle game, and one is a roguelike-y game. So without further ado, let’s get into them, beginning with:

Lorelei and the Laser Eyes

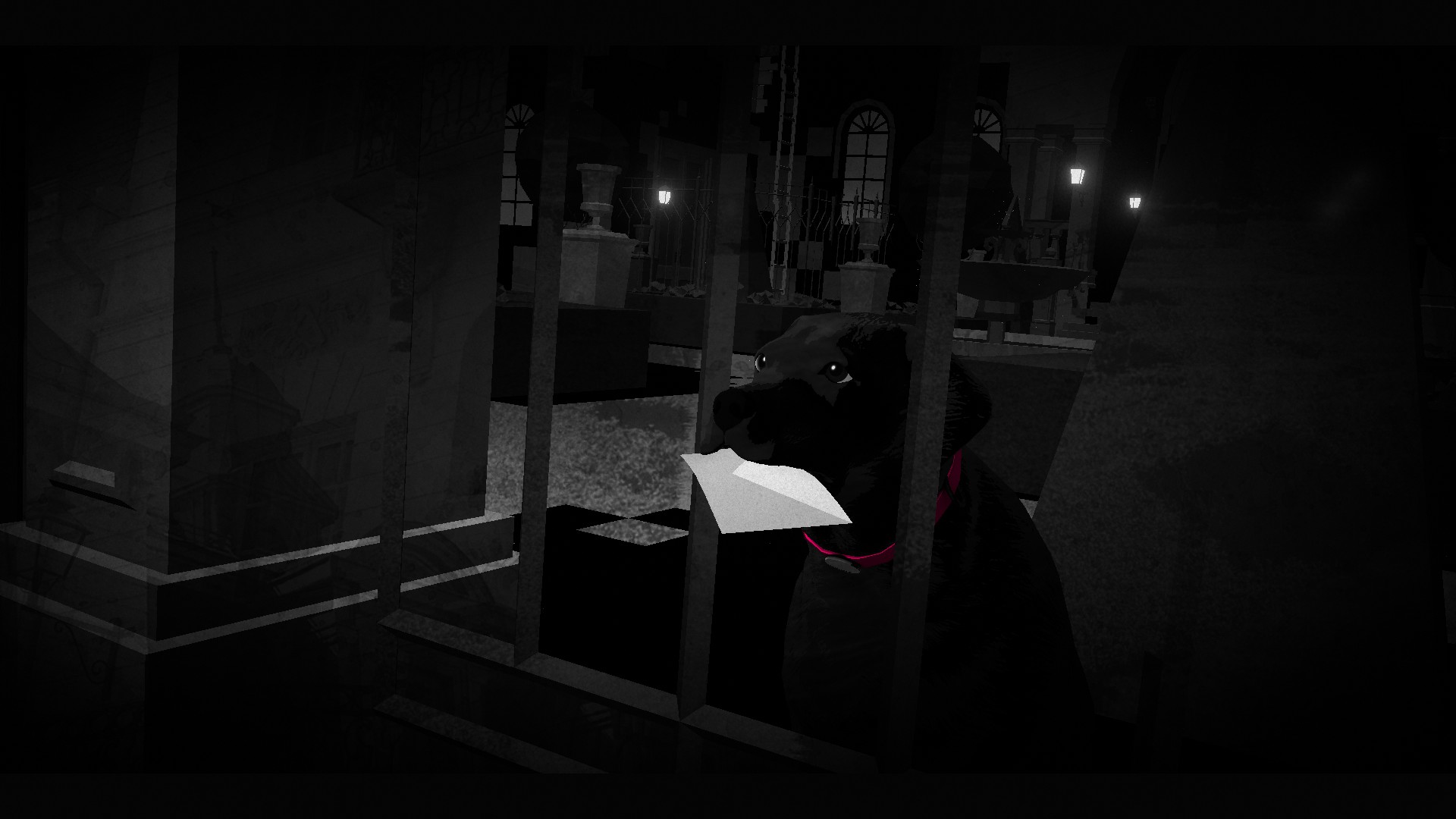

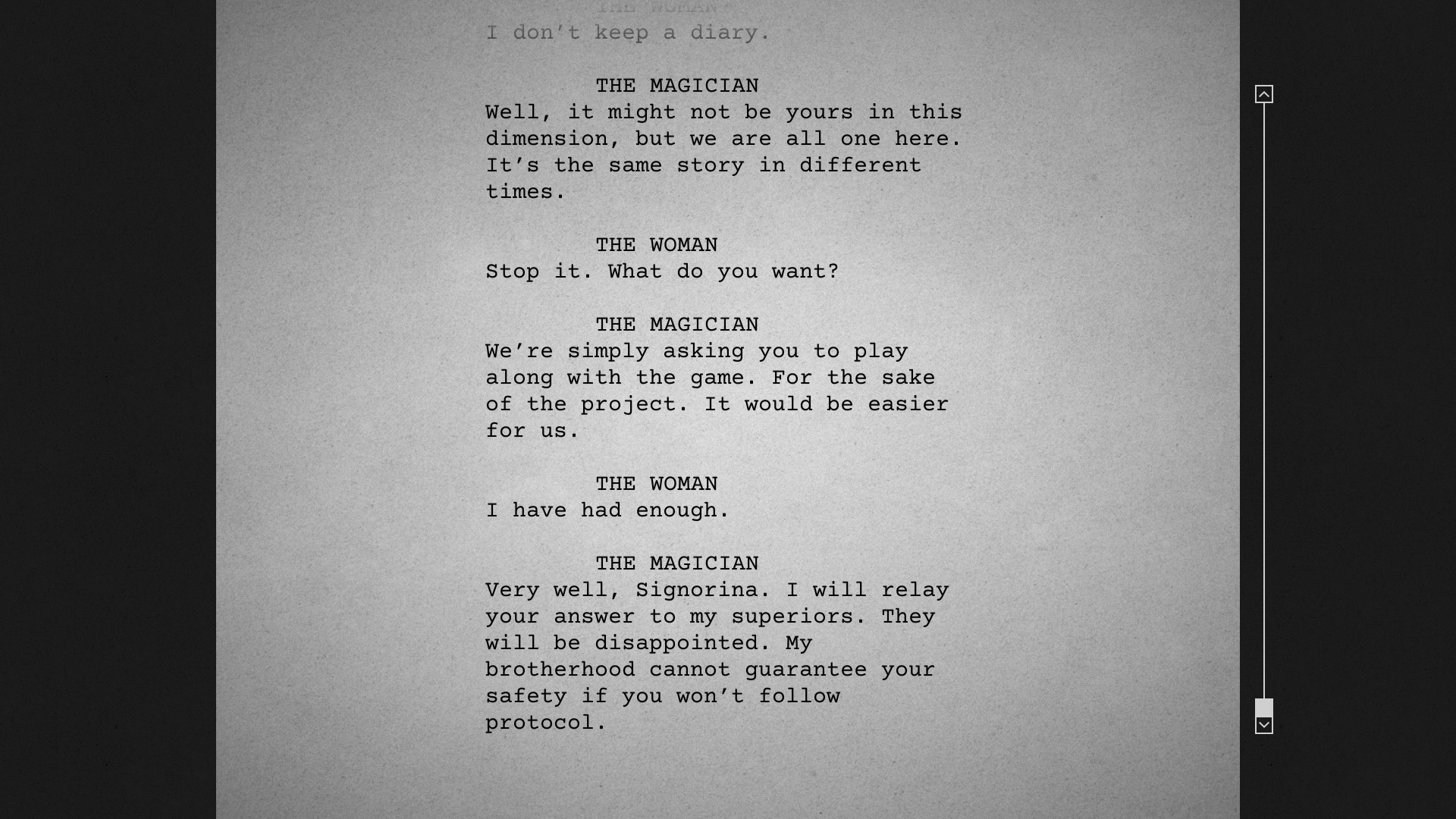

Our first game sees you play as a the intrepid Lorelei Weiss, a lady who finds her way to a strange hotel mansion out in the western European countryside, for reasons initially unknown – is she an investigator, an artist, a reporter, some combination thereof? She appears to be the only guest at the hotel in question, although glimpses and hints of other guests are seen or encountered from time to time, even while there is little to confirm their presence. Controlling Lorelei around this mansion, whose strange and puzzling rooms one gains increasing access to and understanding of as the game progresses, your task is to unravel what exactly is going on here, which is generally done through an excellent selection of puzzles comparable to those in games like La-Mulana or The Outer Wilds (or Myst, Riven, Tunic, Obra Dinn, etc), which is to say they fall under the heading of what I’m increasingly terming “cryptic riddle games”. You go around collecting information and knowledge and understanding – some of which is quite clear in its meaning and its use, while other parts are far more opaque – and with that knowledge and understanding you can deduce what code should be entered in a given padlock, or what instructions should be entered into a computer, or what location to visit (and what action to perform once there) in order to secure a required outcome. Along the way the story of this hotel and the person or people there, including your own character, quickly becomes breathtakingly strange and intriguing, with several layers of reality and unreality, as well as fiction, history, past and present and even future, become entwined in the most curious of ways. On top of all that, without giving anything away, there slowly emerges a very unique and genuinely profound, and actually moving story, which had a lasting effect on me at the end. This game is an absolute gem, and I couldn’t be more pleased I spent time with it this year.

The first thing to talk about in more detail is the very high quality of the puzzles. The opening puzzles are generally pretty simple and all have a similar input mechanism, and in truth that actually had me just slightly concerned once I began playing, but very quickly they expanded to have far more complexity, far more variety, and far more forms of input and solution-testing, than the very earliest puzzles had. That first segment is the only part that I think could have been a little stronger on the puzzle front – though I will admit that teaching the player what to do in cryptic riddle game is hard, and indeed something I’m working on myself at the moment – but the main ninety-five percent of the game is incredibly strong as soon as you’re familiar with the world, the sorts of riddles it wants to give you, and the innovation and lateral thinking it expects from you. Despite my experience with these games there were some genuinely tricky puzzles here that required genuine thought, note-taking and reflection, and even some of those moments where something you think isn’t even part of a puzzle becomes potentially important. There are some clever connections to be made between the world’s various pieces and the information you’re given, and it all plays out incredibly nicely. The core path is also, as far as I can tell, quite like La-Mulana, in the sense that there are so many different sequences in which you can solve the riddles and advance. It also does that thing a good cryptic riddle game should do of giving you some hints to late puzzles very early in the game, both to further obfuscate and mask which hints you should be using now to handle the early-game puzzles, and to ensure that you’re remembering and keeping track of things from early on when you do, indeed, come to those later puzzles eventually. This is really nice technique and this game, like many others in the genre, does this very nicely, and there’s always a deep satisfaction when a clue piece you got near the start finally fits into something and finds it purpose. Overall the riddles here are just brilliant, very inventive and clever, and do excellent work in both written clues and visual clues.

Next is the aesthetic – my goodness, what a beautiful game. Most of the game is in black, white, and shades of grey, but the world you explore is hauntingly beautiful. The developers have done and incredible job of using shape and form a lot in the game world to develop a coherent aesthetic, and also some really interesting use of strange disconnected areas, or graphics, or parts of the game world (it’s hard to describe this until you play) does a lot to add to this very unique style. In one area with a lift, for example, you can actually see through parts of the floor to see the lift as it comes up, and this gives a very unique disjointed and otherworldly, but also completely coherent and unified, sense to the game world. A few things, however, are highlighted by various shades of magenta, and these really stand out sharply form the game world very nicely. Sometimes this is used to draw the player’s attention to important things (as a minor quibble the game does this slightly too much at the very start, but again I understand it’s trying to situate the player who is not experienced with this style of game), but soon it just becomes a visual flourish that is deployed to wonderful effect. This is visually stunning game and I cannot praise its look enough. LATLE also has a fantastic soundtrack – especially in light of URR’s forthcoming official soundtrack, I am really trying hard this year to comment a bit more on sound design, and more generally just continue reworking my brain to pay more attention to these elements of the game experience. The background music is wonderfully ambient, spooky, and evocative of this place, its strangeness, the ambiguity over when in time the story is actually taking place, and has a tremendous range of different sounds for different sorts of places or settings in the game (again, hard to be specific without spoiling) that all come together to a really unified whole. I must, however, give particular praise to the main menu music, which really soothes and raises my soul in a wonderful way, and the final music that plays over the end credits, which is just a glorious treat and brings the entire tale together in the most satisfying way imaginable (especially after the emotional high(s) of the sequence that leads up to it). I’ve been enjoying the soundtrack greatly even after finishing the game – and indeed some of the tracks are amongst those I’ve put forward as inspirations / references for some of URR’s soundtrack! – and it’s just magnificent, adding so very much to an already incredibly rich game.

Alongside the above, the game also has a real sense of charm, and a real sense of humour. These aspects are not as prominent as they are in my other favourite game of this year, but they are nevertheless prominent here as well, and do a lot to help the player settle into a world that is otherwise quite aloof, quite alien, and has a surprisingly heavy and tragic story behind it. The writing is very intelligent and very sophisticated and literate, but also really has a sense of playfulness to it, and is very able to give this overall veneer of play or amusement, or subversion and transgression, to the whole work. There’s a lot of wry amusement in the writing, the character dialogues, the deliberate engagement with and parody of lots of other related works both in literature and cinema, and all of this slight amusement that comes through across the entire game on the part of the writers and designers is a ton of fun to encounter. As with the work of the writers and directors whose projects clearly inspired this, one gets a self-awareness coming through in the entire game which is very gratifying. There are also other forms of charm to be found in the game which I don’t want to spoil, but there’s a lot more to the game than first meets the idea, a lot of very amusing satire, self-referential parody, and quirky little secrets, hidden all over the game world, which I really enjoyed discovering. Despite the overall heavy tone there is also plenty of humour to be found in the game world as well, including some parts that honestly made me laugh out loud with the wit and cleverness the writers had worked into both essential, and side, parts of the game’s progression. All of this, when combined with the game’s deeper ideas and overall quite sombre and mysterious tone, works a real treat, and I really found myself just being pulled further and further into what was going on here – the humour and charm didn’t counteract the darkness and strangeness, but rather somehow reinforced it by building a broader sense of a whole and complete world I was enjoying.

Best of all, though, is that delightful feeling of falling down a rabbit hole the more you play. As the game advances the nature of what is acutally going on here both becomes somehow clearer and somehow more opaque, and more and more layers come into play that I dind’t anticipate when I started off. Again, without going into spoilers, this game has some absolutely amazing “no WAY!” moments, when you realise the scope and ambition of the game exceeds what you previously thought it had – i.e. you thought the game consisted of a, b and c, and even though you haven’t seen all aspects of them, you have a good sense of how those work, and then unexpectedly partway through, d and e are both added, and the entire sense of what you’re doing here and how it connects just keeps expanding outward in a brilliantly executed manner. Part of this is also the overall sense of the game which does slowly unravel itself in the strangest and most puzzling of ways, aside from the puzzles themselves and the discovery of new mechanics as the game advances. In doing so it really hits a lot of the vibes of some of my favourite authors, such as John Fowles and Paul Auster (and to a lesser extent Thomas Pynchon) – that sense of the slightly otherworldly, that sense that there is more to life that immediately meets the eye, that sense of the deepest or strangest or most profound joys or interests that a person might explore in their life, and that sense of taking seriously nothing more than what happens inside a person’s mind and the absolute importance of subjective experience – for, to quote Fowles, “the human mind is more a universe than the universe itself”. This game does very deeply on those questions, very deeply indeed, and throughout the game’s entire unravelling I just found myself time and time again, over and over, being impressed by how much more there was, how much further the rabbit hole went, how well-connected the gameplay and the thematic and narrative elements are… and just the sheer damned ambition of the thing, especially for what I understand to be a fairly small team. In this regard it reminded me of something like Hellpoint for its ability to be a full, complete, massive, detailed experience, with so much care and attention and specificity, and so little laziness or flab.

Finally, beyond all of that, the game wasn’t just a visually and aurally beautiful place to spend time, and a source of genuinely excellent puzzles, and a source of that delightful “falling down a rabbit hole” feeling I so eagerly seek in games and most often find in cryptic riddle games. All of these things were brilliant, of course, and I would still be writing a rave review even if that had been all, but the game somehow also – especially in its conclusion – somehow contributed to be a genuinely moving piece of art, and one I’m really pleased I got to experience completely free of spoilers. It’s a delightful and mesmerizing rabbit-hole that goes deeper and deeper the more you play, unravelling both a fantastic mystery told through really engaging and interesting and novel puzzles, but also a tragedy, and a call to the viewer to not let life pass them by and to seize everything there is to be seized. It has (especially at the end) genuinely significant emotional weight, and in doing so it might perhaps – whisper it – have even elicited a tear or two from me. The game’s finale brings together so elegantly all the puzzles, the aesthetics (for there are several, including some I haven’t shown off here, in order to avoid spoilers about some of the more surprising and clever aspects), and the story you’ve been getting glimpses of but probably haven’t quite pulled together, into something with an incredible degree of consistency between its story and its gameplay, and what it wants to tell you about the mysteries of life and time (in this regard, something like The Outer Wilds is an obvious comparison). What a glorious, madly ambitious, challenging and engaging, utterly delightful and incredibly compelling piece of work this game is, and I recommend it in the strongest terms to anyone who enjoys deeply moving stories of tragedy and life and the human soul, head-scratching puzzles, and absolutely beautiful in-game aesthetics. Oh, and as a final thing, there is also a really good dog in the hotel’s courtyard, and you can indeed pet said dog, so that should honestly seal the deal even if nothing of the above managed it.

Cobalt Core

And now we come to my other favourite game of this year – the wonderful, very challenging, utterly charming and earnest, and frankly just brilliant, Cobalt Core. I rate Slay the Spire as one of the peak roguelite games, and certainly the standard to beat if creating any kind of deckbuilding game, and I suppose I’d long held off trying Cobalt Core – or any of the others that have come out since, for that matter – in a belief that they just couldn’t possibly be better, or indeed as good as StS, so why even bother? I knew I’d play them eventually, don’t get me wrong, but it didn’t seem like a priority. Yet at the start of this year, deep in the quagmire of preparing teaching for 700 students, making huge changes to the lectures and courses I deliver, and dealing with a ton of administrative work as well, I decided I needed a run-based game to help see me through. Do an hour’s work, do a run, then repeat; or do an hour’s work, do a chapter or a battle or whatever, and then repeat. As noted in the Infra Arcana review, this is a technique I’ve found highly effective in the past for getting through work that isn’t at all intellectually demanding, but very time and energy and attention demanding, and so I scrolled over my Steam list and Cobalt Core jumped out at me. Time to give it a go, I thought! So I booted it up, and hopped into my spacecraft with my three animal companions / crewmates for the first time, and set out on my first journey. I cannot honestly say my first journey ended in anything approaching overwhelming success, and certainly not victory, but I was immediately struck by a number of things. Each of these has indeed carried over into my bigger thoughts on this game, and the more I’ve played, the more I’ve come to appreciate the care and attention that really has been put into each of these elements. They grabbed me immediately, but then also continued to expand, and deliver, in run after run, all adding up to a game that I have to say I now absolutely adore.

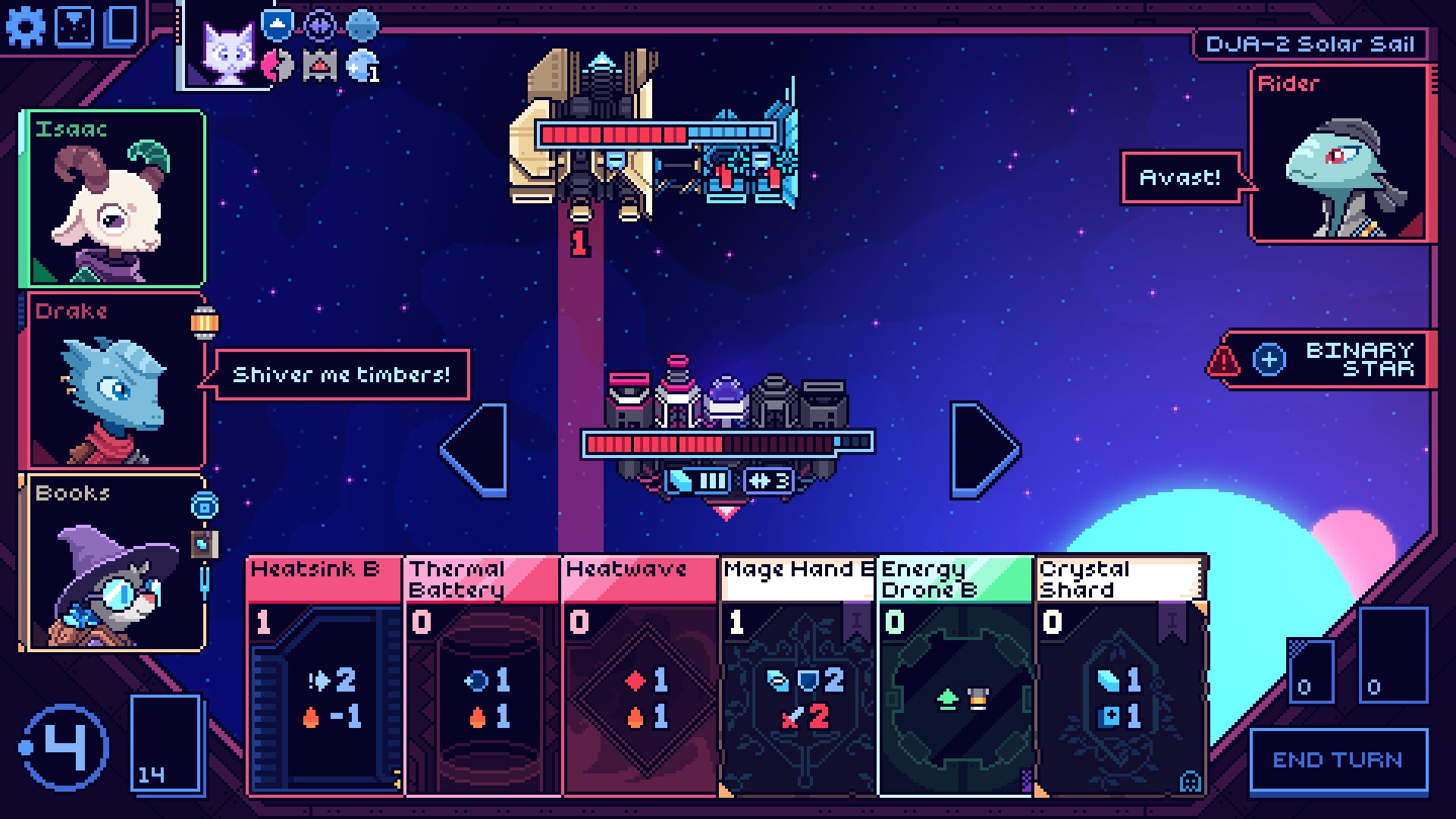

The first of these was the gameplay. Cobalt Core makes three chief innovations over the Slay the Spire deckbuilding norm, and each of these it uses to massive potential. One is the fact that each of your crewmates has their own deck, but you combine three crewmates on a mission – and, thus, you are combining three decks (for a total of 56 “full” decks each drawn from three out of eight crewmates in all possible combos). Some character decks play better with each other, some play worse, but this strategic layer before you even start the game, and the complicated set of different tactical options you get in each playthrough when you’re actually trying to make the three decks you’ve chosen for that playthrough combine usefully, are really delightful, and a very fresh challenge. This is then compounded by the choice of five ships – which each play better with some characters than others – but then again, more fully, by how the ship-to-ship combat works, which is the second major innovation. Managing to do something very unlike Spire, and also very unlike something like FTL, the ship-to-ship combat here involves one ship above the other one, and each part of your ship, and their ship, might be doing something or firing something. This makes a core part of the gameplay being lining the right things up the way you want them, being able to sometimes think quite a few cards ahead, and find interesting interactions between your cards, your ship, the other ship, anything else in the arena, and some potentially very clever ways to avoid damage, deal damage, and manipulate the environment to your advantage. The third innovation is giving each card two potential upgrade paths, rather than one just one. It’s such a small thing, but it’s a fantastic idea, and having now completed the game on Hardest with all 56 decks, I think I used almost every upgrade path at least once; there are always scenarios where B is better than A (even if A is generally better), or vice versa. This gives a wonderful degree of flexibility and even more capacity for crafting a very cunning deck.

The second is the pixel art. The game is honestly just so beautiful, with art that is absolutely crisp and clear and unambiguous, but also has an incredible amount of character. I wouldn’t say the art style is cartoonish, but it’s certainly not going for a “realistic” style (the unrealism of its content notwithstanding) either, but instead something very nicely in the middle, down-to-earth and clear but also with a ton of character and a ton of attention paid to this element of the game. Your cards are clear and just lovely to look at in their own right, but the characters are the real stand-out here. Both the potential members of your crew, and indeed the pilot of every enemy vessel you might encounter, have so much character and soul in them, which is further boosted by some of the many slightly alternate appearances the characters can have based on in-game events, such as looking shocked, embarrassed, afraid, happy, and so forth. The ships, meanwhile, again have so much distinctive character to them (I know I’m using “character” a lot in this paragraph, and I apologise for that, but it’s the best word I’m able to find to address what I’m trying to get across here) and there’s just so much care put into every single visual aspect of the game. The backgrounds are also beautiful and have some very pleasing parallax scrolling effects, and the relics and artefacts you can find are similarly very pleasing to the eye, especially with such a small number of pixels to fit something into. Overall the entire game world has an extremely coherent aesthetic which is always charming, always clear and crisp, frequently very endearing and very funny, but which never gets in the way of conveying the essential information that you’ve got to be giving someone playing a roguelike or roguelite game (and the conveyance of that information is, itself, very pleasing, and looks exactly like everything else in the game). There’s just so much care and attention, even to visuals the player might only see once in their entire time playing the game, and the sense of real commitment to creating something gorgeous to look at just shines through on every screen.

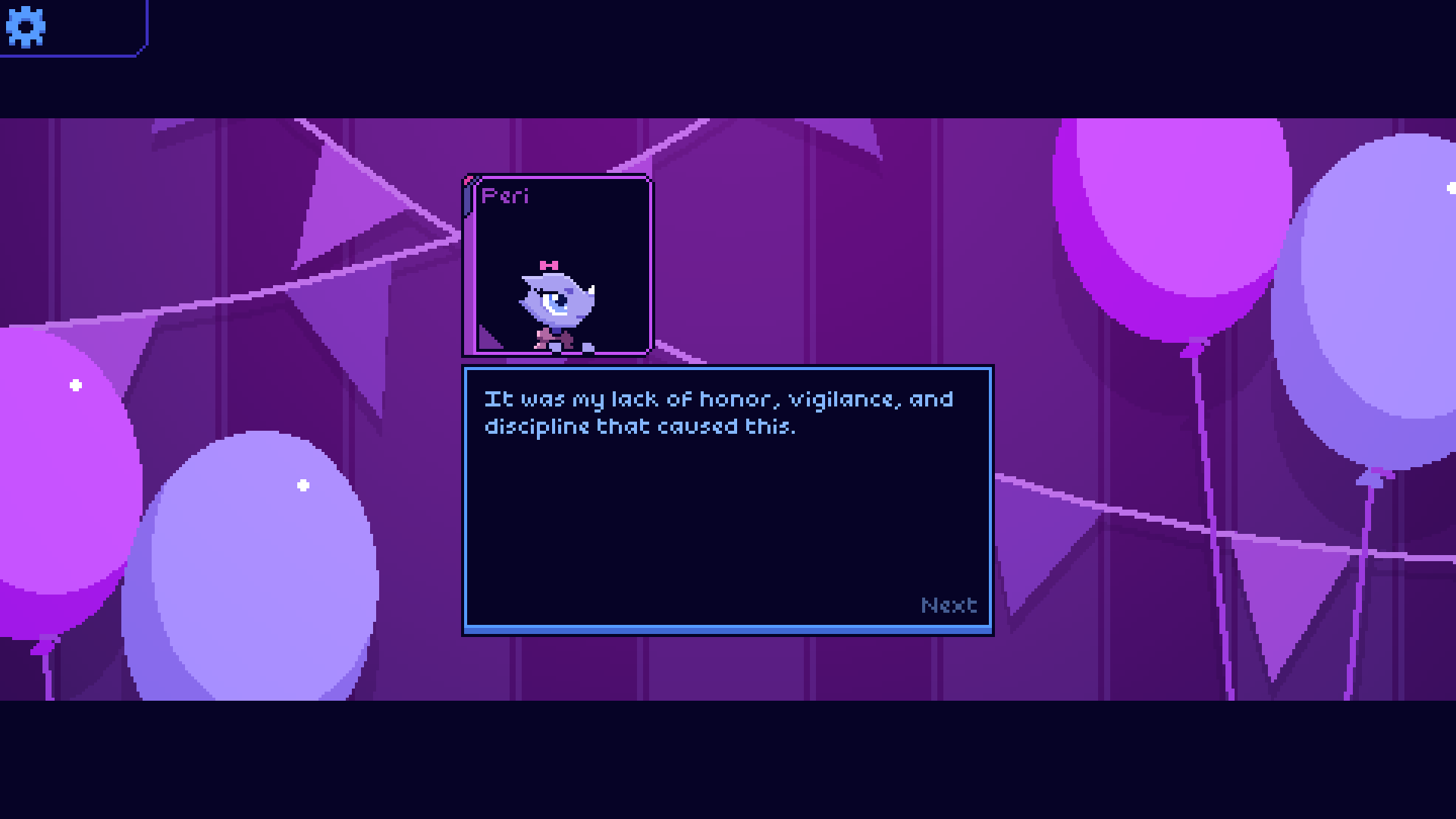

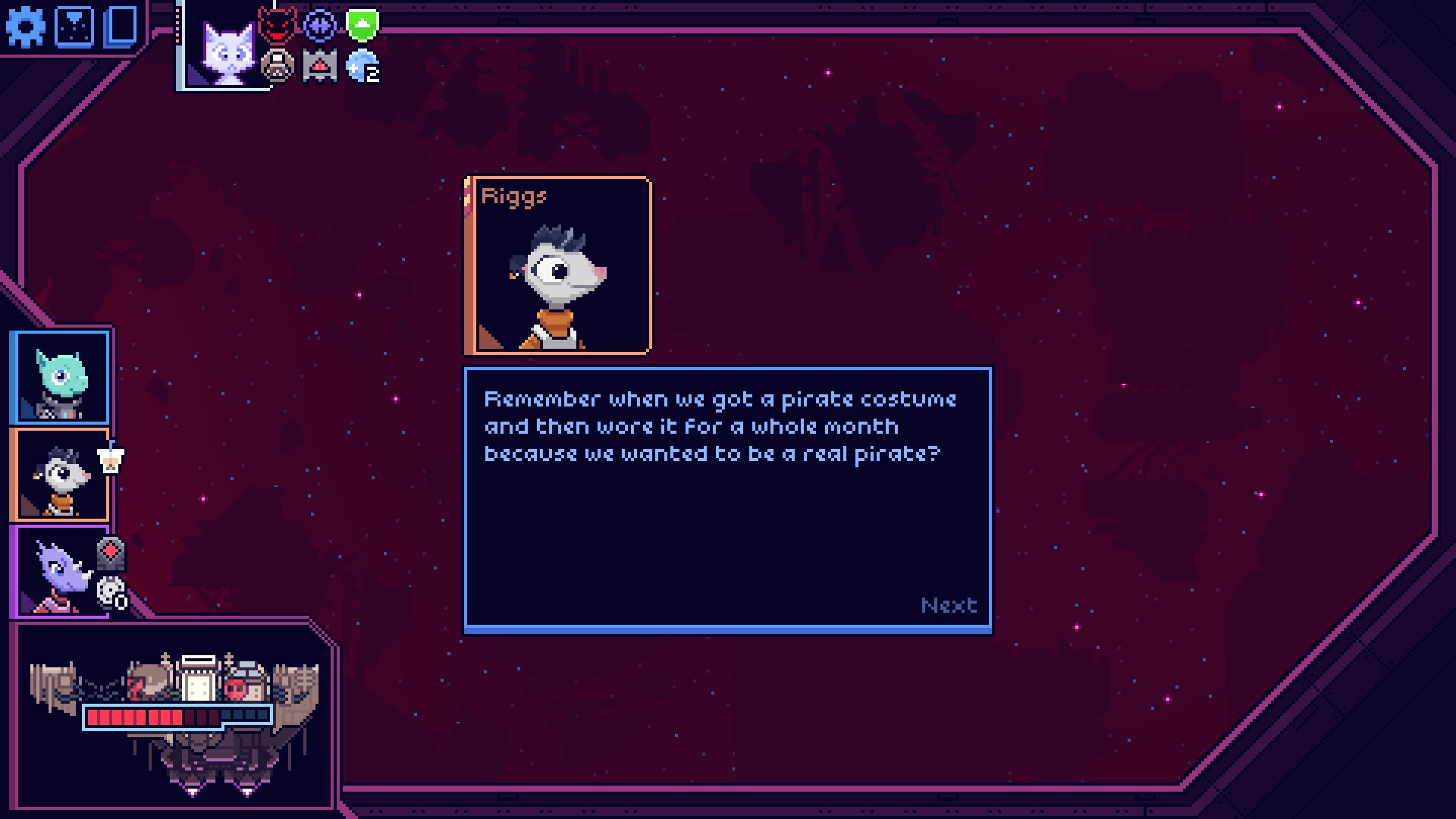

The third is the writing. It is clear the writing follows the same degree of quality as the above, and indeed similar to what I found in Lorelei, with just so much attention paid to the quality of the writing. Your crewmates will often comment on things going on, as will the pilots of the enemy ships you’re fighting against, and there are also characters in other contexts you meet in events and so forth who also have a lot to say. The writing is just so damned funny, and just so damned heartfelt and charming, that it really captured my interest immediately. Each of your crewmates is very well defined in their writing, and even more impressively, has a lot of dialogue that can only trigger under certain circumstances or with certain other crewmates (so in a sense, a Mass Effect comparison here). The writers are honestly masters of their craft – I’ve rarely played a game with funnier, smarter, or more heart-felt, dialogue. Everyone of the characters is just so damned precious, and has so much charm and wit and so many endearing qualities, but also never feels like a pure caricature. They all seem like someone who (generally speaking) has chosen a life of a particular sort and has really leaned into that life and all it brings with it, and yet they’re also just all so gentle and friendly with each other (even the enemies!) and there isn’t even the slightest malice, or resentment, or nastiness, to be found anywhere. This might sound a bit cheesy but it actually works incredibly well, and the whole game as a result has this wonderful wholesome feeling, as if you’re just hanging out with old friends and cruising through the universe for leisure, as much as for anything else. The dialogues are just so witty, and the characters so well-drawn – so far beyond what you’d get in almost any other game, even though actively aiming to be funny.

The fourth was the attention to detail. Again, long-term readers will know that this is a feature, although sometimes a little abstract and hard to pin down, that I rate incredibly highly in games. Cobalt Core has it in spades, in so many ways, but a couple of them stand out. One of the clearest examples of this is the set of conversations that your crewmates can have with each other; it’s a large set, and as I say, it reminds me of how games like Mass Effect enable different little ambient conversations between your team-mates depending on which ones you take on a mission. This is much the same, and although I have now beaten the game with all fifty-six possible crew combinations, I’m not entirely certainly I’ve even seen all of these possible little exchanges. The writers didn’t have to bother to put these in, but they did, and they do a huge amount of work to flesh out the characters, and to provide funny, surprising, and unexpected things that continue to pop up in certain battles, under certain conditions, with certain crewmates, even after you’ve hit your hundredth hour in the game and gone beyond. In a similar vein, I’m very impressed by how reactive the crewmate comments are to what happens in a certain turn in a battle, as well as these conversations between crewmates. I remember one turn I started with an unusually high amount of energy, but my draw was so weak I could barely do anything with my cards; I played what I could, ended my turn, and at the end one of my crew said “Is… is that it?”. I laughed out loud – not just because it’s an amusing comment, but because it speaks to exactly the kind of design that I so enjoy: taking the time to think of as many edge cases or unusual happenings as possible, and then ensuring that something interesting will occur in as many as possible, and the player will notice these rare little moments. Many other examples of this beyond the writing exist, but there’s just so much polish and so much care here, and it shines through in everything the game has.