Welcome all to 2021’s (six months delayed) edition of “Some Games I Played in [Year] and What I Thought Of Them”! What a year it was. Much to my surprise (and I’m sure the surprise of everyone else) I released Ultima Ratio Regum 0.9 and I’m now actually beginning work on URR 0.10 (!) with hopefully a yearly model for major releases, barring further health disasters and so forth. I published a ton of research articles on live streaming (e.g. this one, and this one) and esports (this one) gambling-style mechanics in gaming (this one), started preparation for finally teaching game studies as I’ve been doing now in 2022, and was generously funded by the Japanese Hoso Bunka Foundation to study Japanese and Australian live streamers in a project I’m conducting at the moment, and will be publishing findings from in the next few years.

As for games, by my count I played 17 titles this year. Last year’s “winner” was quite clear-cut (Rain World) but this year we have more candidates competing for this top title – The Curious Expedition, The Outer Wilds, Hellpoint, and Streets of Rage 4, to name just a few. As before I’ve written up a little review of each one, so without further ado:

The Curious Expedition

We start, of course, with a roguelike, and one I have been looking forward to playing for a long while. The idea of a roguelike-y game set in the age of exploration sounded absolutely gripping to me (and not just because I’ve been reading Patrick O’Brian’s genuinely fabulous Aubrey-Maturin series in the past year so, which I’ve had to carefully space it out in order to not exhaust its wonders too quickly). I met the guys from Maschinen-Mensch in Germany during the International Roguelike Developers Conference / IRDC all the way back in 2014 (!) and Riad and Johannes are a fabulous pair with a very clear vision and a great sense of humour – but I’m not one for playing early access games myself, and so I wanted to wait until the entire thing was finished. I’m pleased to say I was not disappointed.

Despite the wonderful premise and some obvious thematic overlaps with bits of URR, I confess that it took me a little bit to really “get into it”. At first I wasn’t clear about some of the aspects beyond the expeditions themselves such as how fame worked in the game, or larger “campaigns” of expeditions – but once I got a good handle on all of this I absolutely loved it. My third expedition was the one that really sealed the deal for me, mainly because my entire party died. Playing as Charles Darwin we first began to run out of water, since I had not fully appreciated that water was (almost) required for traversing desert regions; then my team’s sanity was reduced to nothing and bad things began to happen. Our donkey bit one of our other team members and so I had to shoot the donkey and use the food to reduce my party’s stress; but then another party member fell into a spike trap, got an infected wound, and later died, not before asking us to convey a last message to his wife. Later on we encountered a pack of hyenas, and since I had acquired some dynamite I thought it a brilliant idea to use the dynamite to dispatch these enemies… without quite realising that when it said group damage, it meant everyone in combat. Having thus violently detonated my prized Persian translator, we headed south again until the Scottish soldier on our expedition reached a critical level of despair and shot himself, after which I butchered the dog that still remained, staggered around a little longer without water, found the golden pyramid… but before I could get inside, Darwin succumbed to his wounds.

And that was it, I was hooked!

The gameplay is complicated and varied, with a large number of permutations and different scenarios which can happen, especially once things start going wrong; in turn there are many different strategies for survival ranging from pacifism to big-game hunting, stealing as much native loot as possible to befriending every native one finds, using various otherworldly abilities, and much else. There’s also a wonderful mix of inspirations here – there’s a lot of Jules Verne to be seen, but also a lot of non-fiction elements as well, a lot of Lovecraft, a bit of more general “adventure fiction” (Robinson Crusoe and the like), some Hammer horror, some Ray Harryhausen, some John Carpenter, and various other inspirations besides. There are a wonderful range of genuinely surprising moments, that fabulous feeling when you discover a game is bigger and weirder and more full of secrets and intriguing things than it previously appeared. On a thematic level, meanwhile, I also like how the game handles contact with tribal peoples – there’s no white saviour stuff here, the tribes have their own interests and lives and motivations, and the “Standing” system (as in, your “standing” with the local natives) works very well for influencing how you act toward them, and vice versa. Your explorers and the native peoples are on a fairly even level – sometimes you steal a statue from them and get away with it, sometimes you anger them and their hunting parties destroy you, and sometimes you become the best of friends and trade hallucinogenic mushrooms – what’s there not to like? Aside from that, the music is lovely and atmospheric, the pixel art graphics are entirely beautiful, there’s a huge amount of variety in what can happen – especially when things go wrong, as in any good roguelike! – and a huge satisfaction when you just survive an expedition by the skin of your teeth. Fantastic stuff, and one of the highlights of the year for me.

HyperRogue

Keeping for now with the roguelike theme, we come to one of the strangest of all. I had always had mixed feelings about the aesthetics (now I’ve played it I actually rather like them) but I had long been intrigued by its promise of being a non-Euclidean roguelike. Classically-styled roguelikes (including my own) of course take place on a square grid and while a couple of roguelike-y games have moved into the hexagonal grid option, such as Hoplite, the setup we see in HyperRogue really is unique. The world is split into many dozens of areas which use this strange geometry in distinctive ways and all feature a unique or semi-unique set of units and other features (like trees, or lava, or whatever) which interact in some way with the other pieces in that area. Whereas distinctive areas in other roguelikes often have several if not over a dozen unique creatures or elements, here each area has only a couple – but it’s enough. The design integration of the various pieces is sufficiently tight that each area poses a genuinely unique threat even when there’s only a handful of unique aspects, and the game’s 1hp system (it is essentially like chess in that you die when you are “checkmated”) always keep you on your toes even when you enter a new area for a very first time. Yet at the same time one does get a very unusual feel from this game in part because the game world is so explicitly infinite, but also because of nature of this strange hyperbolic infinity is certainly not what the human mind is use to. It’s a very unusual world to explore and feels like nothing else I’ve ever played.

Nevertheless, it’s the designs in some of these regions that are the real stand-out points of the game. Some areas are genuinely fascinating – the Palace, Galapagos, the Dragon Chasms, the Overgrown Woods, and Red Rock Valley all stand out as being exquisitely and creatively designed and often very charming on top of that – although a few others, such as Free Fall, Windy Plains, and the Lost Mountain, didn’t do that much to grab me. Nevertheless this is a world with over 50 areas, and only a handful were at all disappointing; it’s a tremendous achievement to have found so many interesting mechanics of terrain and enemies and movement types on in this strange hyperbolic world to offer so many unusual and compelling challenges, and especially challenges that can meaningfully ramp up as well. When playing one is expected to collect ten “treasures” in each area each of which will increase the number of enemies spawning, but collecting 25 unlocks something additional; I have yet to find any area where one cannot reach 25, or indeed significantly more, if one is not careful and thoughtful about your moves (or you go back after unlocking extra abilities later on). There are also a number of quests including the main quest to “win”, but there are sidequests as well which often seem to involve exploring or navigating some of the strange aspects of hyperbolic geometry, or using in-game items and skills to do things which would be trivial in our world but are remarkably challenging in the HyperRogue world – such as “walking to the middle of a circle”. The game gives players a lot of information about what’s going on as well, with clear descriptions of enemies and how they function and how the various tiles work, all of which are extremely welcome in a 1hp game that features peramdeath. HyperRogue is completely unlike anything else, really takes full advantage of its strange geometry, and I enjoy it a lot – and although I haven’t quite got a win yet, I am getting close.

Slay the Spire

One of my most played gaming experiences in 2021 was Slay the Spire, a vaguely roguelike-ish deckbuilding game in which the player uses, constructs, and plans with one of four possible decks to overcome a series of increasingly challenging battles. These battles are fairly randomised in terms of what you might and the precise moves that each enemy uses on each turn, while the levels are also interspersed with various (often quite amusing) events or unusual characters who can be traded with. One of the true joys of games that go heavy on the procedural generation front is the need to use what you find instead of creating a character build that you have a lot of control over. Slay the Spire hits this mark extremely well, always requiring innovation and new ideas from the player if they want to succeed. Of course there are shops, and one generally gets a choice of which card (if any) to add (or remove) to one’s deck, but you are nevertheless in a state of constant innovation in games like this where no two playthroughs will ever be identical. A card that might be tremendous on the deck you had light time becomes worthless or even detrimental on the deck you’re running now, while very occasionally an item you rarely have much use for becomes exactly the thing you need to make your deck strong enough to beat the later enemies. There are hundreds of cards and the decks have a lot of depth and interest to them, and there are so many different ways to approach the game and try to secure victory. The visuals are also lovely and the crisp and the soundtrack is both atmospheric and pleasingly dramatic in battles.

What really stood out to me, however, was how this game was to play for someone coming with an immense amount of roguelike experience, but essentially no deckbuilding experience. Each time you complete Slay the Spire you unlock a higher difficulty, known as a higher “ascension level”, and these gradually ramp up in difficulty all the way up to 20. What I noticed was that my roguelike experience quickly got me to between 2 and 4 Ascension levels on all characters within a few days of buying the game; but then my lack of deckbuilding game skills REALLY kicked in and my play just ground to a halt. There were so many cards I was automatically rejecting because I wasn’t thinking through the full synergies, because the draw, hand, and discard pile mechanics are so deeply alien to me; I could factor in things like attack, defence, multipliers, stacking damage, various mechanics that integrated those; but the cards (for all four characters) that involved manipulating the discard, exhaust, draw, and hand mechanics just didn’t click in my brain in the same way. It was a really interesting experience to learn how powerful the draw mechanic can be, and how strong synergies between the various card piles can be, and these were all things I had overlooked at first in my purely roguelike approach to the game. It has been a tough but highly rewarding experience for me, and at time of writing I’ve hit Ascension 20 on one of the four characters and I’m getting close on the other three. I have become far better at using these deckbuilding mechanics, yet I am also self-critical enough of my play to see that is where I still struggle; sometimes complex and weird combinations of items and cards just don’t occur to me until it’s a bit too late, while watching some of the strongest players playing it highlights how important these niche strategies really are. Overall this has been a tremendous amount of fun to play, and also a fascinating experience of playing a game that sits between a genre I knew perhaps better than any other, and a genre I had never played in my life; the combination I experienced of high-knowledge and zero-knowledge was very unusual and intriguing, but even if you don’t bring that to it, this is a tremendous and deep game.

Nuclear Throne

Nuclear Throne had been on the radar for a while. My loves of danmaku-style games and roguelikes are both well documented and this seemed like a game that could combine them both well, with some lovely pixel art and a nice sense of humour. It did all of these things and I got maybe 6 hours of play out of it – the core action is very fast and very compelling, the game balance between weapons and ammo types is handled nicely, the world is very aesthetically pleasing, there’s some great post-apocalyptic humour here, and the soundtrack is great. I got most of the way to the end of a first playthrough after various attempts, especially once I’d got better at using melee weapons and had a good idea of how to bounce shots, handle some of the tougher enemies, reach a couple of the secret levels, and so on. However, despite my enjoyment of the game eventually two (somewhat related) issues sadly turned me off the game for good. Firstly, the game was not good at giving you total control over things which killed you; multiple times I literally didn’t even see what had killed me, and once or twice I couldn’t even work out what had been fatal even after the game tells you what kills you. The most infuriating was a time when – having learned that cars explode and kill you – I specifically avoided shooting cars, cleared out the map, the portal to the next level appeared… but it turns out the portal causes nearby cars to explode, and there was a nearby car, and it killed me. A death like that is just frustrating garbage, and even as I got to know more about the game the number of these sorts of deaths did not seen to decrease.

The second issue was that the early-game struck me as extremely repetitive. Once I’d got even a little bit of mastery over the game there was nothing remotely challenging until reaching the snow levels, and the important thing is that the early levels were not varied enough to make replaying them compelling. Take a look at the early levels of some classic roguelikes like NetHack or DCSS or indeed the early battles / stages of modern roguelikey games like Isaac or FTL or Into the Breach – these are permadeath games which know you’ll be restarting a fair bit, and so they’ve worked hard to make sure the early game is always interesting, compelling, and challenging. As far as I could tell Nuclear Throne had unfortunately not done this. I think if either of these two issues had existed in a vacuum – the deep repetitiveness of the introductory section, and the possibility for totally unexplained death – I might not have been quite so frustrated, but the pain of repeated deaths I didn’t see coming combined with having to redo the first few trivial levels again and again was just too much. I loved a lot of what this game had to offer (and YouTube videos show me there’s a lot of cool later content I’m missing out on!) but I just couldn’t get past the combination of these two problems. Gorgeous pixel art, fabulous world, a great sense of humour – but much more variety needed especially in the early game, and it would also have benefitted from some more transparency as well about objects or object interactions that might be fatal.

Bioshock Infinite

This year I finally got around to trying Bioshock Infinite. I thought the original Bioshock was excellent even if a) all the critiques about the meaninglessness of the “ethical choices” are completely on-point and b) it has definitely generated far too much scholarly interest for what it is. The sequel was a good play but inevitably less original and intriguing. I thus had high hopes for Infinite, a brand new and equally striking setting with a lot of compelling – and sadly still contemporarily relevant – thematic elements (racial injustice, Christian fundamentalism, American exceptionalism, etc). I gave this one a few hours but unfortunately it wasn’t doing it for me. I found the world absolutely captivating – the level of attention to detail in the architecture, the posters, the clothing, the way people spoke, the general creation of this particular historical-geographical slice of Americana and its vile racist elements were superbly and grippingly depicted… but the combat left me quite cold, and I didn’t find myself with a particular desire to push on and figure out more of the plot. In the first case the combat seemed surprisingly flat, and I wasn’t finding myself getting into any kind of a rhythm at all. Has the widely-praised bullet-ballet of Doom 2016 spoiled me for first-person shooters? Perhaps, although as below I found myself playing Halo 4 this year and the gunplay there still did it for me. One issue for me here was definitely the fact that all the weapons seemed to fairly mundane and very “real-world” weapons, in contrast to the much more inventive and sometimes unusual or esoteric weaponry of the original game.

Secondly, as for the plot, given the famous “Would you kindly?” reveal of the original Bioshock I knew there was going to be some kind of crazy reveal (or reveals) the story progressed, and although I didn’t guess them exactly, having now looked up the story I see that I was loosely thinking in the right directions. Yet even without that knowledge there just wasn’t much pushing me on to uncover what was going on in the story; I would have loved to see more of the world but I didn’t find myself with much interest in the character or the other characters we’d heard a little about. The Comstock character (the founder of the city) seemed intriguing based on the hints dropped to the player in the opening segments but it against wasn’t enough to push me to keep exploring the city in order to find out what was going on. I suppose I wasn’t really getting much of a sense of how the world worked, how the everyday banality of existence functioned. This is something which has always been very important to me in worldbuilding-heavy games (and is something I actively look for when I travel IRL) and I didn’t get a real sense of how the city of Columbia actually worked when you weren’t rampaging through it. It’s an interesting piece and I can see how impressive it was at the time, but unlike some other games – I just don’t think it has aged that well. A disappointment.

Hellpoint

Wow.

So: I’d heard about Hellpoint as a “Dark Souls in space” game but I’d also heard a lot of critiques which highlighted that the game was apparently very buggy, regularly crashed and didn’t save progress, and that it was also possible to get stuck in the world geometry in various ways and be rendered unable to continue. The Souls-in-space label was incredibly appealing but I have a pretty low tolerance for bugs and glitches myself compared to what some people can put up with (especially in early-access games etc), and particularly in a game that I expected to be very difficult (it was) and very unforgiving (oh, it was!) I knew that was the sort of game in which these kinds of problems would prove unusually frustrating. Eventually however I decided to give it a look – not expecting much, I confess – and I was absolutely blown away. Hellpoint combines a fascinating mix of Lovecraft, Event Horizon, cyberpunk, Doom, a hint of Alastair Reynolds, and a dash of Asimov, and what it comes out with is pretty extraordinary.

The player is tasked with exploring and uncovering the mystery behind a vast abandoned space station, and one which is most like a city than a station, and strongly evokes the striking “megastructural” architecture in Soulsborne games. This feels more like an entire civilization than anything else, and as we explore it we uncover all manner of strange creatures, foul deeds, astoundingly cryptic puzzles, hard-as-nails bosses (and enemies more generally), and secrets hidden in secrets hidden in secrets. The aesthetic style and art direction are absolutely incredible and from my very first moment I felt completely immersed in, and convinced by, this world. The combat is tight and works well and introduces some interesting new aspects not found too much in other games of this sort, and as the game went on I continually found myself struggling to believe the size and richness of the game universe. In difficulty it strongly echoes Dark Souls 1 in particular, not just because the enemies are difficult but also because the world is so unforgiving and so unfriendly to the player, and that made it a total delight to conquer (and in doing so felt very meaningful). Many of the little polishes in the game world are very idiosyncratic and unique as well, and those stood out to me too – although small, they spoke so strongly to a larger world far beyond what we were seeing in the game itself. In my entire playthrough I am also pleased to say that I didn’t encounter a single crash bug, and the only issues I found – like a corpse flipping around a little bit in ragdoll mode, that type of thing – were few and far between, and easily ignored (especially as someone who actually found that stuff somewhat entertaining in the earlier Souls games). Hellpoint evoked everything I’d loved so much about the earlier From Software games – an astonishing difficulty and user-unfriendliness, extremely cryptic mechanics and interactions, a deep and baffling world, incredibly labyrinthine and twisting level design, and genuinely stunning art direction. I cannot recommend the game enough.

(On a side note the developers were kind enough to bring me on as a playtester in their forthcoming DLC. It was excellent, and I am not kidding when I say the art direction exceeds, in terms of originality and freshness, anything in Elden Ring – a game I’ll of course talk about in next year’s entry. I’m excited for the release when it finally appears!)

Age of Empires II

Now here’s an older game which really has aged well. About two years ago I suddenly discovered that not just is Age of Empires II still played competitively, but that it makes an astonishingly gripping competitive game, and suddenly I was fascinated by it once more. I remember playing this a little bit at my secondary school (the final school before going to university) in the UK when I was younger, but I also remember – and this is a little childish but speaks to the sorts of things that somehow seem to “matter” when you’re a teenager – that most of the other bright kids I “competed” with at school tended to love it, and so I (naturally) felt obliged to dislike it and double-down on playing the Command & Conquer games instead for my real-time strategy fix. Ha! The absurd behaviours of youth. Nevertheless, upon my return to the franchise after a decade and a half I was hugely pleased by what I found here. The campaigns are interesting and varied – I don’t think they support really optimised min/maxing play as much as they should and can sometimes feel perhaps a little slow (and I don’t claim to be a top-tier AOE player or anything of the sort), but they do really nicely evoke various interesting turning points in history, famous campaigns, leaders, and so forth. The designers have also really developed the variation in the civilizations, so that each group (e.g. Mesoamerican civilizations, South-East Asian civilizations) both look and play distinctively from other groups, and each civ within each group plays at least somewhat unlike the others. The visuals are of course gorgeous and wonderfully evoke all different kinds of architectural styles, environmental biomes, and military units. This has been a real pleasure to return to, and if you haven’t watched any competitive AOE2, believe me when I say it’s extremely compelling and deep, and has a pleasing potential for surprising for unexpected events that one tends not to find in other RTS games.

Halo 4

A(nother) blast from the past! In my teens I was a committed Halo player, especially Halo 2 in which I was active both competitively and in the “tricking” community – I even once put together a video of a number of ways to get the infamously secret “scarab guns” as well as tips for various launches and glitches (one or two of which I know were new back in the moment), but sadly it has been lost to the ravages of time (though I searched for it in the process of writing this blog entry!). I even contrived to find my way into (I believe?) the very first phase of Halo 3’s closed beta (which was an incredibly exciting experience for someone who was only 17!). While the main appeal of the Halo games for me was always their excellent multiplayer and the matchmaking / ranking systems, I was quite fond of the campaigns as well. Although the series is known for some pretty dire levels (e.g. Sacred Icon, Cortana) I always found the Covenant a very thematically compelling enemy, the visuals of the megastructures and cities and so forth very distinctive and awing, and on higher difficulties the game does offer a solid challenge. There are some excellent speedrun strategies out there as well – in particular this Halo 2 speedrun from a GDQ a few years ago stands out. Nevertheless it has been around a decade since I last played a Halo game, but 2021 turned out to be the year of my return.

One of my best friends is currently playing some of the Halo games for the first time and so I felt keen to jump into coop; although a replay of some of the older games was good fun, I had never played Halo 4. Overall I enjoyed my time with the game (purely singleplayer) and it was a welcome and nostalgic return to the series in many ways, although I do think the game failed to innovate as much as it might have. The visuals are excellent and striking as ever (I even wrote an academic piece about Halo’s megastructures a while back) and the sense of the world we spend most of the game in is exquisite; the opening sequence as the ship you are cryo-sleeping in gets “discovered” was also strong. Of particular note are some of the new enemies who combine with each other and even with the terrain in some pretty interesting ways, and this was a very fresh addition to the combat that wasn’t necessarily feeling stale, but had certainly become familiar. The new weapons are somewhat interesting and distinct from existing offerings, while things like the voice acting and so forth were very strong as usual.

However, although the main thrust of the story was interesting and helped flesh out some mysterious points from earlier games, it wasn’t anywhere near as bold as it might otherwise have been. In particular I was sad to find myself immediately fighting Covenant within just a few minutes of the campaign, and even if we later switched to the new enemies, I feel it stopped short of a much greater narrative leap – to completely leave behind us fighting the Covenant (although I would accepted the odd group of fanatics here or there, but not a gigantic fleet seemingly a full half the strength of the original civilization) and having us instead focus on the Forerunners. I recognize in terms of pacing I’m sure the goal here was to start us off with something ordinary before moving into the new enemies, but the more I played on the more I felt this was a mistake. An introductory section with far less combat or even no combat (a la the intro to Half-Life 1?) and perhaps having some Covenant allies in the area, or maybe even the discovery of this Forerunner planet and what it contains being the thing that makes the Covenant splinter into a peaceful faction and a fanatical faction… I do think any of these options would have been stronger and bolder than starting us off again with the classic enemy. This is especially the case since Halo 3 ended dramatically with the Covenant becoming humanity’s ally, in a resolution that – for a game fundamentally about a near-invincible space marine blasting hopeless aliens into eviscerated oblivion – had a surprising amount of emotional weight. The splintering of the Covenant is fine, but it could have been a much more interesting narrative moment, or even (my preference) omitted altogether.

And this is, in a sense, illustrative of my main issue throughout the entire game: too little of the new, and too much of the old. Instead of having a few new enemies which have a few intriguing interactions, why not an entirely new suite of enemies with a full set of interesting interactions that constantly problematises what order things should be fought in and constantly changes the relative threat levels of the enemies present on the level? Instead of having a few small sections where the Forerunner architecture and the terrain you’re walking on are actively working against you, have that be a central part of the game, and build in new kinds of mobility (and maybe ways to prevent terrain moving?) to help you navigate a treacherous, shifting world. Instead of having bursts of the Chief-Cortana storyline peppered throughout in surprisingly small number, make this the crux of the game’s narrative. Overall I found Halo 4 to be a very pleasing return to a franchise that was once a central part of my gaming life, and there were a number of genuinely interesting ideas here; but I only wish they had taken those ideas further and further towards their logical conclusions, instead of relying for so much of the game on the tried-and-tested formulae of Halo to get the job done. There were some bold strokes here, but in too small a number to push the series in what could have been a new and compelling direction.

Ancient Domains of Mystery

Yes, another roguelike! My own classic roguelike history has focused extensively on NetHack and Dungeon Crawl Stone Soup to date, both of which I remain very fond of. Angband never particularly gripped me (I like my Tolkien as much as the next person but nothing more than that), Brogue’s graphics I find difficult to parse and distracting, and the original Rogue is just a bit too bare-bones for me… but then there was ADOM. Some of the things I knew about the game intrigued me – the opacity of the code and the fact that some things about it were still unknown even after literally decades of play spoke to a level of mystery and nuance that seized my interest – but other aspects put me off, such a lot of strange obscure rules one really needs to know in order to have any chance of winning (such as the importance of what you kill first, how many you kill, how many cats you kill, and so forth), and some aspects of the classic fantasy setting which didn’t especially captivate me. Nevertheless I gave it, for the first time, a proper try this year. Overall it was genuinely fascinating to finally play one of the only major classic roguelikes I haven’t played before and it definitely stands out – it’s deep and complex as they all are, but also quirky and particular and curious in a way which is somewhat comparable to NetHack, but also distinct. I can’t quite decide whether I liked the quirks or disliked the quirks, but they definitely make it distinctive – and either way what really defined the game for me was the introduction of mechanics like aging and the use of more common mechanics like alignment in ways one doesn’t normally see in other games. The aging mechanic in particular I found strange and interesting, although again I struggle to assess whether I found it a positive or negative element of play and strategy. Nevertheless, it’s a mad and sprawling piece of work, and one I’m really glad I finally got a proper sense of after all these years.

DOOM Eternal (again)

Readers may remember that after being blown away by DOOM 2016 I naturally gave DOOM Eternal a shot last year, but was sadly disappointed. Yet I decided to give it a final try this year, and I am so glad I did. After internally accepting that this was a very different game and that we were just going to be thrown into the melee with no explanation – and thus mentally almost “pretending” that I hadn’t played 2016’s version – I swiftly discovered what an amazing piece of work this is. The lore scattered throughout the world is fine (some of it I think is quite neat and interesting, although some of it is just bizarre wacko nonsense) and I have mixed feelings about the platforming sections (sometimes a nice cool-down after a particularly intense fight, but also sometimes an astoundingly frustrating break from the extraordinarily compelling core combat), but the combat dance is, indeed: absolutely sublime. The speed with which one navigates the terrain, fights enemies, and has to make a range of decisions around weapons and abilities, is absolutely blinding. I do not mind admitting that when I first watched a few bits on YouTube I was taken aback – yet it’s striking how rapidly one gets into it. Once you really get the hang of the combat it’s incredible how rapidly one can traverse terrain, bring down even the toughest of enemies, keep your resources at acceptable levels, and plan many steps ahead, even in the most intense battles. The designers have balanced the fights really well to take account of the terrain, of the weapons you have available at various points in the game, and also to push the player just up to the point of thinking “This battle is absurd I cannot survive any longer” – at which point a last, final wave of enemies spawns, you barely manage to slay them, and you are left with that fantastic feeling of having just survived (which of course roguelikes for example are also known for doing so well). It is an exquisite bullet ballet, and it’s incredibly captivating, even (in my view) when facing a certain notorious enemy that a lot of players and critics were not keen on.

I also should say something about the world you fight through. The worldbuilding elements are in many ways much looser than DOOM 2016 – you visit a huge range of completely bonkers places with little connection to each other, and many of the levels are quite explicitly game-like, by which I mean they could never feasibly exist as real places because real places don’t have rotating bars of fire perfectly positioned for you to dodge past – but the world visuals are truly stunning. They give a genuinely apocalyptic sense of the Earth’s ravaging and transformation by the demonic invaders, as well as more broadly the many diverse and strange realms of DE’s version of Hell. There’s a lot of creativity on display here. Yet the world is also one that enables comedy: there are some really nice physical jokes throughout both the main campaign and the DLCs, mainly focused on your character’s insatiable lust for violence and destruction, yet also coupled at the same time with some witty and amusing deconstructions of that very same trope and its (near) ubiquity in first-person shooter games. The soundtrack is of course absolutely incredible (my personal favourites are Meathook and BFG 10000), and the secret “toys” you can collect around the in-game world are once more hugely endearing.

Nevertheless, it was overall an absolute joy to rip and tear through the campaign and the DLCs on Nightmare difficulty… and yet having cleared those, I cannot help but notice that “Ultra-Nightmare” option sitting there, on the main menu. Taunting me. Calling to me. Telling me again and again that I like permadeath games.

But I’m not going to try it.

I’m not.

…

I mean… probably.

However, I do have to say – the DLCs were a disappointment. While there were some great set-piece battles and the world’s visual design remains extraordinary, the new enemies – coming in after the developers must have had months and months of feedback and player responses to the original game – were the real problem. The truly baffling thing is that these enemies simply make the game worse, and this is such an odd choice that one – understandably! – sees it in so few games. The new foes almost exclusively make the game slower, they reduce the creativity in combat the player can display, they are often intensely frustrating and kill you or cripple you without you even being aware they had appeared on the map, and they demand a fundamentally different (and less interesting) kind of situational awareness and thinking. While some are slightly more justifiable (the Armoured Baron is… okay, I guess?) and others less so (the Stone Imps were infuriating and unnecessary), the Cursed Prowler merits our particular attention. Hard to spot (because it looks almost exactly like another enemy and blends in with many backgrounds), this vile creature renders you unable to dash if it hits you, and can only be defeated in close combat with a particular weapon you may very well possess no ammo for. This almost always spells instant death, and this – unsurprisingly – created intense frustration for me while playing the DLCs. In a game centered around rapid movement the game prevents that movement, a single hit from them (especially since they run away after hitting you and can only be killed, to remove the no-dash effect, in close combat) often means, simply, death, with no possibility of survival.

Yet… before condemning everything I have to ask myself: is this genuinely a crappy design choice, or am I failing to understand how clever it is? (For instance, Dungeon Crawl Stone Soup is infamous for this – many decisions that are actually clever and interesting meet with tremendous public opprobrium, hence the long-running meme that the DCSS devs “make the game worse with every release”, even though this is really not a defensible position to take – although what happened to the Silver Stars, DCSS dev team?!). But: I have squeezed and palpated and wringed out the cerebral fluid from every last neuron in my game-addled brain, and I just… I cannot find a design justification for this enemy. I just can’t. Some folks I’ve seen on Reddit and elsewhere have said “WeLl It’S iNtErEsTiNg BeCaUsE yOu HaVe To PrIoRiTiZe It” but, no, that doesn’t actually make something interesting – in fact it is the literal antithesis of interesting because it takes all the variability and flexibility of the game’s combat and movement and resource management and suddenly boils it down to a single absolute imperative which you must obey at all costs, kill the Cursed Prowler. Now, if the player merely took incremental damage upon being cursed but kept all movement options and could kill it with any weapon, while the Cursed Prowler was extremely evasive and tried to then avoid you at all costs; that might have been an interesting enemy. It would become one of many to consider, and when you get cursed it would become one factor to weigh up against others – how much health do I have, how far away is the Cursed Prowler, do I have a weapon that can reach it, am I in a good position to hunt it down, etc. (Maybe it could even multi-curse you, like the Basilisks in Dark Souls before that early patch). I can actually imagine that a DOOM Eternal style enemy specifically coded to hit you with some status effect and then evade everything could be – when used sparingly – an interesting challenge. But in its actual implementation the Cursed Prowler is the epitome of the new enemies in the DLC, which is to say a foe that slows combat, reduces combat options, forces prioritisation, and requires a specific obscure way to kill. On balance I think I am glad I played the DLCs – the visual world design remains spectacular, and there were some good fights, and a compelling boss halfway through the first one – but I don’t know whether I can honestly say they gave me $40 of value, when I could have just replayed the later levels of the original instead.

Baba Is You

This is a very interesting puzzle game which requires some talking about. You – sometimes – control a small sheep-like creature called BaBa, and the gameplay involves manipulating blocks with words in them (such as “Is” or “And”, or objects like “Wall” or “BaBa”) to form new sentences whose existence reshapes the possibilities of the game world. Or, to put it another way: the behaviours of the game world’s objects are determined solely by the creation of sentences using these in-game word items. If the sentence “Wall Is Stop” exists in the game, then you cannot walk through walls; but if you remove the “Stop” then the sentence is incomplete and you find yourself able to walk through walls; and if you change it to “Wall Is You” then you find yourself controlling all the walls in the game! It’s extremely trippy but fascinating once you get the hang of it, and I found myself excitedly playing several dozen levels, especially in the aftermath of my 2020 disappointment when I finally played The Witness. There wasn’t any of the “other stuff” in the Witness I found so frustrating – here instead we just had a series of puzzles and nothing else, and the puzzles were interesting, challenging, and required a really unusual form of thinking from the player.

However, although I believe the game has 200+ levels I decided to move on after completing around 40. It’s strange because I’ve been desperately longing for a really compelling puzzle game and for quite a while I thought this was it, and yet nothing I’ve played so far (aside from The Outer Wilds, below) has really pushed my own personal puzzle buttons in the last couple of years anywhere near as much as custom handmade logic puzzles (see below). I think what turned me away from continuing down this path was simply that the game felt like work. There was something about the grammar of the in-game sentences again just wasn’t completely lodging itself in my brain – I understood them perfectly well but more than once found myself having to pause and think through the impact of something, or pause and think through whether a particular sentence would be valid, rather than it just becoming natural as time went by. Perhaps this is intentional? Or at the very least, the normal experience? I couldn’t say – yet it frustrated me deeply as I found I was never able to get into a rhythm or anything like it with the game, and I always felt like I was working very hard to get through the levels, and there just wasn’t much in the way of joy or pleasure upon completing them. Instead I just felt relief – and that’s an emotion I feel on completing some piece of work or administrative task I have no interest in, but is not the emotion I should be feeling after completing every level of a game. I called it a day there, and having watched a few interesting streams of it (which I did enjoy), I don’t regret it. It’s a really interesting piece and one which “should” have given me what I want in a puzzle game, yet also one that didn’t keep me coming back for as long as I had hoped.

Z

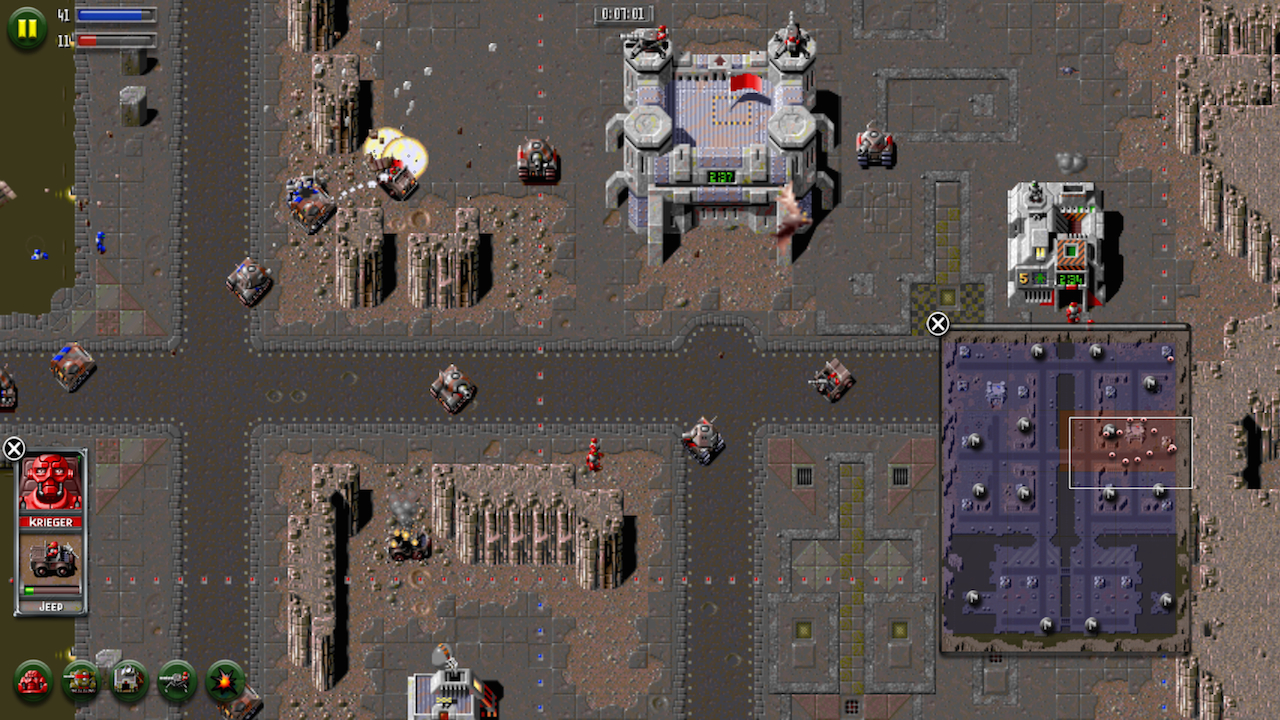

Another blast from the past – early real-time strategy game Z. This is a very interesting (or maybe I should just say “strange”?) game – you control groups of foul-mouthed wise-cracking robots as you battle over various worlds with a range of weapons, vehicles, and terrains (the terrain in this can be destroyed and altered, also, which is an interesting little twist and perhaps anticipated that same kind of idea in Tiberian Sun, for example). However, whereas the earlier Command and Conquer games I (as a very game-dedicated 7-10 year old, but nevertheless a 7-10 year old) found very challenging but just about winnable, I always found Z extraordinarily difficult to the point that I had to give up on it upon first trying the thing two decades ago. If memory serves I was never able to get past around 5 or 6 levels into the singleplayer campaign, being constantly out-produced, out-maneuvered, and (in my childhood sense of these things) out-thought by the game’s AI. Unlike many RTS games your units are at a premium here – every squad of three or four soldiers is important, but every vehicle is essential, and something precious to be preserved and fought over to the bitter end. (In this regard it is, in a sense, the exact opposite of the scale and grandeur of something like Supreme Commander, or to a lesser extent Total Annihilation). This is further intensified by the fact that vehicles can be captured rather than merely destroyed, and so much of the combat in Z often balances on a knife-edge of one more vehicle, or denying the enemy a lucky shot, or getting a good first shot in a tank-vs-tank battle before the opposing force is able to respond. A single vehicle, if well-preserved, can last you an entire mission, its health bar something you’re constantly looking at and factoring in to your tactical choices. Even the projectiles fired in-game have a real weight to them, and every time a tank shell is fired it feels like a meaningful actor in the combat – projectiles move “slowly” compared to most games, and can easily hit something else if the intended target moves out of the way!

As a result of all of these unusual factors, the combat feels far less pre-determined than combat in many RTS games, even those praised as good esports games (e.g. SC2) – you can always throw away a battle here, but you can also almost always eke out a tremendous amount of value from only a few units with the right strategic and tactical choices. What all of this means is that although the pace is more “sedate” than many other games, every choice, every single unit constructed, every movement or battle committed to, resonates through the battle. I have to say I really loved this – Supreme Commander sadly left me a little cold last year, but Z was a wonderful playthrough this time around, and the sarcastic and often crass humour, combined with the charming and distinctive visuals and its unusual differences from most other RTS games really marked it out as something worth a play. Unsurprisingly it was not as challenging as it was when I was young – and yet it is still unusually difficult. The AI here – paging Tommy Thompson – is distinctive, and seems to be more cautious and cunning than one gets in other RTS games of a comparable era, perhaps as a reflection of this “every unit matters” game design philosophy (and perhaps simply having fewer pieces to coordinate allows a greater coordination of each unit for the same processing power?). The enemy AI is not afraid to retreat, and the enemy AI is surprisingly competent at bringing just one more squad of soldiers or one more vehicle to bear at the vital moment in the most important place.

However, the only problem is that the version you can get on both Steam and GOG is apparently a PC port, of a mobile port… and it’s a bit horrible. It’s still playable but it doesn’t have any of the niceties of your modern RTS, so be warned – but if you can get past that and deal with the dreadful controls and a couple of AI bugs, it’s worth a play for the RTS fan.

Control

This was an interesting one – I’d read so much praise about the game before I played it that I was definitely looking forward to something more original and intriguing than, sadly, what I actually got. The main setting – the endlessly-shifting and now apparently supernaturally-infected “Oldest House” – is very interesting and a really pleasing place to spend one’s time in. Imagine an architectural version of Area X from Jeff VanderMeer’s “Southern Reach” trilogy and you’ll have a good idea. At the same time it had something of the megastructures of “bigger-budget” SF games or the endless vastness of a location like Black Mesa in the original Half-Life – a sprawling complex where so many different things take place that nobody has a completely comprehensive image of the institution, and it grows and expands and shifts with something approaching a life of its own (one might also think of the castle in the Gormenghast books). This was a fantastic setting and I enjoyed exploring the House, and yet at the same time I sometimes found navigation of this space somewhat confusing – in a frustrating way, not a beguiling and intriguing “it’s fun to get lost” way – and I would have actually liked some more variation in the interiors, as there’s only so many strangely-deformed grey stone Brutalist interiors you can look at before you feel the need for something else. I also felt the game moved extremely fast at the start with introducing its places, concepts, characters, etc – it felt like we’d come into the second act of a story having unfortunately missed some important narrative foundations in the first act.

I was also quite disappointed by the combat, which I had expected to be far more varied than “gunplay with some supernatural abilities” – after all the praise of the game I’d read I confess to being rather surprised by this. There didn’t seem to be much here that other games hadn’t already done in a large number of other cases. In turn, the variety of the enemies – almost all basically just possessed humans, some of which had supernatural powers – was also rather disappointing. Given how severely the main enemy in the game, “The Hiss”, had corrupted the building, I think there was a ton of missed opportunity here for some extremely weird creatures to be prowling the corridors. In essence 90%+ of the enemies were just “zombies” who shot various sorts of guns at you, and this just seems disappointing given the weird otherworldly stuff going on elsewhere in the game. Maybe I was missing out on some fascinating stuff further down the line, but after a few good play sessions of several hours I just didn’t find myself entirely gripped, and this was intensified by the strange feeling that we weren’t going to get a clear narrative resolution about what was happening (which, having now looked it up, seems to sort of be the case?). As such, I have to say I am surprised by the praise this got. I don’t disagree that the visuals are sometimes striking, but there just wasn’t much new in the gameplay, and the rare but very gripping and compelling parts where the architecture did strange things were, for my money, too few and too far between.

Streets of Rage 4

Now we come to Streets of Rage 4. Beat-em-up games not generally my thing, although I enjoyed Golden Axe and Streets of Rage 2 back in the day as much as the next person (for those who might be interested, this first ever no-death max-difficulty playthrough of Streets of Rage 2 that was live streamed a little while back is completely bananas, and well worth one hour of your time). Streets of Rage 4, however, had captured my imagination with its beautiful art style; its hilariously accurate and self-aware riffing off 70s/80s martial arts / urban action films where everyone wears bandanas and fingerless loves and the streets are, indeed, full of rage; and what I’d seen in the trailers, which seemed to imply the presence of a combat dance that might be massively satisfying once fully mastered. Having put a lot of hours into the game I can now confirm that it is indeed, absolutely delightful. The gameplay is tight and fast and there are many many options for dispatching your foes and maintaining and building a larger and larger combo. The enemies are all distinct, with different sets of attacks and different ways of approach – many can be easily approached via jumping kick, some are best approached on the ground, while a few enemies are best tackled via grabs. This range of ways to fight them couples nicely with the massive range of ways they fight you, with diverse attacks of various speeds, reaches, some ranged attacks, some faster or slower enemies, and some which close with you quickly while others maintain a distance or actively try to evade you. This combination of interactions between the player character and the enemies leads to complex, rapidly-changing and flowing combat situations, where the player rapidly responds to shifting situations based on their knowledge of their character’s capabilities and the capabilities / movements of the enemies on the board at any given point. With some of the simpler enemies one can easily “trick” them into behaving in simpler ways and stacking up to be beaten to death, but most of the more complex enemies defy most of these tricks and demand that even a skilled player must use their full arsenal of attacks, especially if you are trying to get a long combo. The combo system is excellent and allows you to rack up towering scores if you are able to chain together hits on enemies without being hit oneself, which soon becomes the real challenge once one has mastered the basics.

The visual style in turn is absolutely beautiful. The characters are all hugely distinctive and endearing (bosses and enemies as well as our heroes) and the artists have done a fantastic job of really emphasising the different physical, clothing style, attitude, or size characteristics of each figure. Everyone in the game looks stylish and interesting and all are beautifully animated. This is true for the slouching “skater”-esque enemies; the muscular hulking taser-happy cops; the “art gallery” girls with their stylish hair and badge-adorned jackets; Mr Y and Ms Y, our two main villains who have definitely been shopping at some of Singapore or Shanghai’s most stylish fashion outlets; and everyone else occupying this beautifully stylised world. Much of the game looks almost like a high-quality graphic novel, with bold artistic strokes and flourishes – and a good sense of humour as well – highly evident throughout. Even more delightfully, sometimes these graphic-novel-esque visuals will intersect into a boss-fight, with comic-style “frames” of action appearing in the boss fight. It’s astonishingly pleasing and fast, dynamic, and gripping, and gives a really wonderful distinctiveness of the game and what it has to offer. I found myself comparing it to something like XIII (remember that?) and SOR4 certainly does the graphic novel style as well as XIII, albeit differently. The soundtrack is also just wonderful, with over two hours of funky / techno music that perfectly captures the game’s attitude and has some particular stand-out tracks, such as “Character Select”, “Funky HQ” (a great name for a song), and “Rising Up”. As one YouTube wit opined, “Whereas most games have a soundtrack, the Streets of Rage 4 soundtrack has a game” – and they are not entirely wrong. This is a great game with excellent gameplay, a wonderful sense of art and setting and humour, a tremendous soundtrack, and so many callbacks to an earlier era of gaming.

Handmade Logic Puzzles

I regularly do the Guardian’s Quick Crossword puzzles (sufficiently non-trivial but not unreasonably time-consuming) and I used to do their Sudoku offerings until discovering this world of custom puzzles which have completely superseded what the Guardian can offer (though their “Hard” puzzles still require at least a bit of thought and sometimes a couple of more advanced techniques). In particular I have become a huge fan (as I think many have) of the YouTube channel “Cracking the Cryptic“, and it has become one of my primary forms of gaming video consumption during the Covid years. I generally do for the puzzles that take them around an hour, although I’m pleased to say I have been able to conquer some of the two-hour puzzles; my general target time is 50% more than they take (so if they take 60 minutes, I aim for 90) and given that they are two people whose job is literally solving puzzles and who have been on the national UK puzzle championship team and all that, I confess that I think my own times are pretty damned good. Logic puzzles like this are a huge joy to me and I enjoy them a lot more than pretty much any contemporary puzzle computer game – with the exception of, for example, my 2021 game of the year.

In particular, three stand out to me as being especially excellent, and if you’re into logic puzzles I really cannot recommend these enough. Firstly this one, known as the “Miracle Sudoku”, both presents a very compelling and interesting ruleset and seems completely impossible to solve when you first open the grid. There are only two digits and although the rules allow for a little more deduction and a little more restriction of possibilities than in a traditional sudoku, it just doesn’t seem viable that you’ll be able to fill in the grid. And yet it can be done, without even the slightest guesswork, and I’m very proud to say this was the first tough-ish custom sudoku I solved, and incredibly satisfying it was. With this one in particular there was something very magical about the process by which the board unfolded, especially once you got to filling in some of the higher-numbered digits and realizing how restricted they already were despite none of them being in the grid at the start.

The second, this one, built on the “skyscrapers” sub-type of sudoku, which I had a little bit of experience with already, but nothing on the difficulty of this one. Ordinarily skyscraper puzzles have numbers on the outside of the grid which denote how many “buildings” you could see looking in from that direction, where a number in the grid is the height of a building. So on a sudoku row of 163758492 you could see 5 from the left – 16789 – but only 2 from the right, the 2 and then the 9 – that would therefore mean a “5” would be outside that row on the left and a “2” would be outside the grid on the right (assuming both clues were present). This puzzle, however, instead uses the outside numbers to denote the first number one could not see – i.e. the first one hidden behind the taller skyscraper – if one were looking in from the side. It’s a far harder variant but was a really joyous and interesting solve.

The third, and perhaps the most ridiculous, is this one, with a ruleset so complex that you need to find it in a separate PDF here. This was one of my longest solves to date and wasn’t helped by the fact that I contrived to overlook the “easy” (take close note of those air quotes) method by which you were supposed to get the puzzle started, and instead went down my own huge and slightly mad chain of logic in order to get to the same point. What makes this sudoku especially wild is that you don’t actually know at the start which rules apply to which parts of the grid, and so a large part of solving this one is working out which rules could not apply to which areas (and therefore what the rules for those areas must be instead) while also, of course, trying to fill in the relevant numbers to actually complete the puzzle. I absolutely adore these sorts of long, detailed, winding, complex logic puzzles – I think in large part because they stand so apart from the focus in so many contemporary puzzle video games on crisp or elegant or quick puzzles – and they’re a real inspiration to me on the puzzle design front. One of the few things I can thank Covid for is absolutely getting me back into logic puzzles, and it’s so exciting to have discovered this whole universe of custom rules and custom-made challenges.

Stellaris (again)

I last played Stellaris all the way back in early 2019 – in the Before Times – and after a cool 500 hours I felt I had really exhausted everything that was to do in the game. It’s a staggeringly-sized SF space civilization simulator game, where you can do everything from enslaving other species to use as food, building megastructures around promising-looking stars, engaging in pitched battles with extra-dimensional invaders, forging a galaxy-wide coalition of like-minded nations, supporting a multicultural (multispecies) renaissance of trust and mutual understanding, transforming your civilization into cyborgs, building a interstellar slave society where conformity is enforced by deep-space black sites around every planet, forging a cryptic alliance with eldritch psionic entities who might occasionally decide to consume one of your planets – and more. I absolutely love it. While the game lacks the seriousness and philosophical / sociological depth of something like Alpha Centauri (the masterwork that it is), Stellaris makes up for it in the sheer variety of what can happen and its excellent (and often very witty) writing. However, in the intervening years much had been released which made me think the time had now come for a return. My Steam page told me that thanks to the new expansions and updates, players could now lead a galaxy-wide corporation with all the humour and satire that could come with such a thing, explore creative and well-written micro-stories of deep-space archaeology and relic discovery, play as silicon-based “lithoid” creatures who subsist on wholesome diets of delicious minerals, spy on one’s fellow civilizations and spark diplomatic incidents among their allies, build trade links and connections that spanned the galaxy, take part in galactic politics and potentially get oneself elected (“elected”) as galactic dictator, enjoy far more interest and variety from making “first contact” with other civilizations, recycle the population of one’s enemies (or, indeed, one’s own population) into zombified armies or sacrifice them on the altars of your death-cult, or even destroy the very stars themselves.

How could I resist?

It is, of course, excellent. All the new features add a tremendous range of extra variation to the game (which was already absolutely, freakishly jam-packed with stuff that could happen) and in particular the massive new suite of diplomatic options have brought a lot of new interest and mechanics to the game. The added species variation is always good, the rebuilt trading / economic systems work well, and planetary management – especially for larger, more sprawling empires – is much less tedious than it once was. However, the new espionage system is rather flat. There are some amusing and interesting outcomes for it but one quickly gets to know the possible operations and their outcomes, and – for me at least – it quickly became just a standard thing where I would be constantly launching particular operations (gather intelligence and steal technology) over and over again. I haven’t looked up the experiences of other players, and perhaps I am way behind the meta on this, but those seemed to be more than adequate for my needs, and the pricing on some of them seems extremely odd. The “sabotage starbase” mission type, for example, appears expensive in terms of espionage resources for what it actually does; if you could target a specific starbase and destroy it (if a smaller / weaker starbase) or destroy a large number of its modules (for a larger / stronger starbase), that would be one thing, but such a high cost to destroy a single module in a single starbase and some modules are immune to being sabotaged?! Nevertheless: great stuff overall, and I’m sure they’ll flesh out the espionage system further with more options, and more balancing, and in later patches. It was a very enjoyable and rewarding return to a completely mad and extremely enjoyable game, and I remain excited to see what Paradox build into the game next.

I also could not resist making and playing as a 2021-appropriate meme species, as evidenced in the picture above.

The Outer Wilds

Ultimately we must now come to what ultimately has to be my game of the year (insofar as I ever think of things in such terms) – The Outer Wilds.

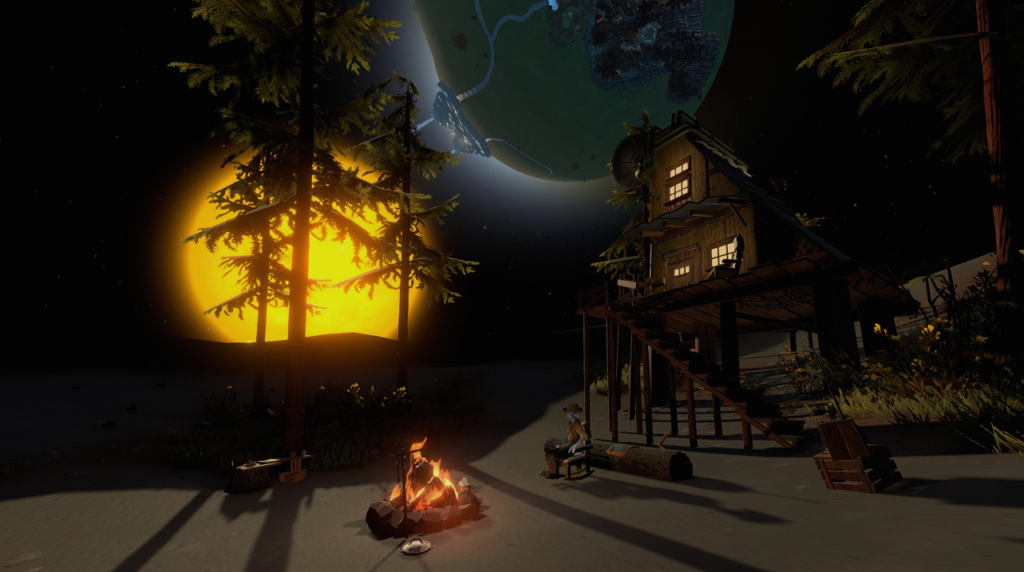

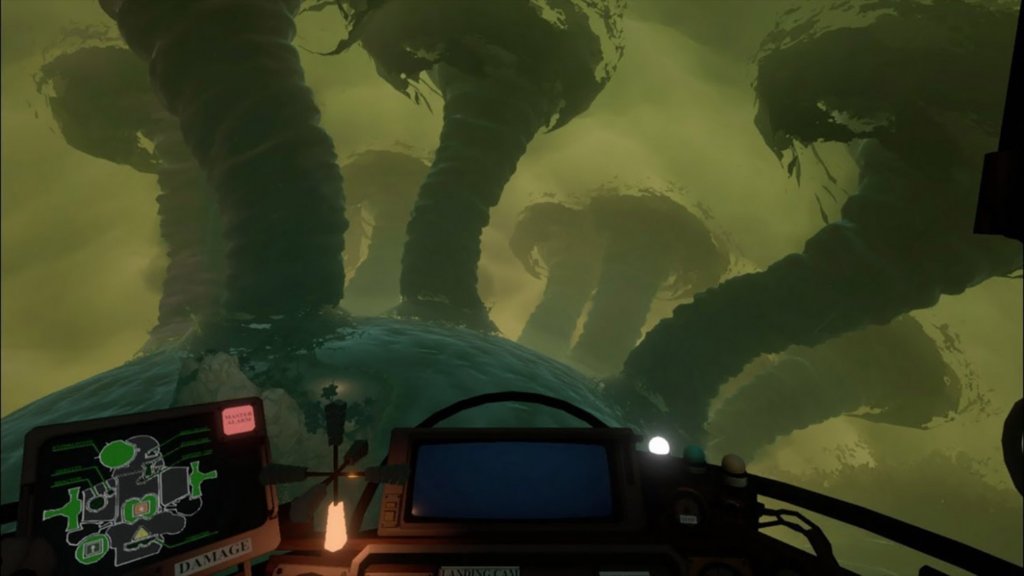

In The Outer Wilds you control a particularly bold and exploration-inclined member of an alien race from a planet called Timber Hearth, as you set off into their local solar system to discover the mysteries behind both the disappearance of the ancient “Nomai” race, and why the solar system appears to be stuck in a time loop. Every 22 minutes the sun of your little solar system explodes, consuming everything (as supernovae tend to do) and sending you back to your planet, from which you can then once more set off and plan another interplanetary trek. The system consists of around a dozen objects including planets, space stations and a comet. Some of these you will spend a large amount of time on while others will only be given a handful of visits, yet are cryptic and confusing enough that it might take you quite a while to understand what you actually do there. You gain no new abilities or tools as the game goes on and instead the knowledge you gain about the solar system, its objects, and its past inhabitants, is all you have to push you towards new discoveries and strategies and areas as the game progresses. The physics of the solar system are well-modelled, with gravity and acceleration behaving in appropriate ways and encouraging you to really get a handle on moving within a 3-dimensional space, expertise that comes in extremely handy both when in your ship and when exploring these locations on foot. The visuals are gorgeous and extremely pleasing to look at for long numbers of time-looped explorations, and the soundtrack is somehow simultaneously evocative and profound on the one hand, and whimsical and charming on the other, a tone which fits the game perfectly. Aside from the main quest and puzzles it’s also just a lovely place to spend time in – the solar system feels (mostly!) warm and welcoming, and it’s so easy to get back to where you were that you are never discouraged from exploring again after an unfortunate death.

You are given access to a charming little spacecraft with everything you might ever need (well maybe not quite everything) and essentially free reign to explore the system. You gain no power-ups, no new items or abilities, and so all you gain is knowledge that can be used on later cycles. The solar system itself is beautiful and interesting and full of diverse objects. Each of the planets and moons and the comet (and maybe one or two other locations) all have very distinctive feels to them – they use different colour palettes and sound effects, and each demands a very different response from the player. One world requires the player to think hard about timings and what part of each 22-minute cycle they arrive on; another encourages you to dodge a number of roaming cyclones (shown below); another encourages you to really think about the world as it moves through its environment and how those environmental changes might affect what you’re able to do on it; another plays with space and geometry in strange ways which require you to rethink ideas like size and the inside of something being always contiguous with its outside; and so forth. None of these puzzles have any particular system to them in most cases – though there are a few puzzles which a particular set of so-called “quantum” ideas in them – and it’s much more about taking stock of the game world as it’s presented and trying to work out how best to navigate it, how best to discover what you need to, and what sorts of solutions make sense while still keeping with what you’ve already been taught. It’s a highly unusual approach to puzzle design but is actually the sort of thing one found in older “adventure” games where you were sent out into a world and just expected to figure out the idiosyncratic logics that governed it.

The main crux of the game, however, is its wonderful set of puzzles. As above you never gain any new abilities so all puzzles are solved via knowledge, and this means that all the puzzles are potentially right there in front of you – but you just don’t necessarily know it. This experience evokes something of the classic detective novel where a throwaway line in the first chapter (“She glanced over the room, noticing the expensive paintings, lush carpeting and empty ashtray”) unexpectedly take on a vital significance once more information is obtained (“Wait, you’re saying that he never smokes? Are you absolutely sure?”). This means that if the player knows what to do in order to complete the game, the player can simply start a new game and win in around ten or fifteen minutes by simply doing the things that need doing; but when you don’t know what those things are – where should I go, and in what order, and what should I do – a first playthrough can instead take dozens of hours. These hours are spent exploring every inch of the world, learning more about it, learning how to get into areas that previously seemed inaccessible, learning how to manipulate the game’s systems in ways that were always there in front of you but didn’t make sense until you had the essential piece of information. Within these the puzzles take various forms with some being to do with timing, some to do with navigation, some to do with unique mechanics present in the game, some to do with figuring out the meaning of obscure terms or phrases, and others simply to do with taking a good, long stare at the environment, and thinking really hard, until something comes to mind. Because essentially none of the puzzles really “repeat” in any way and all are essentially unique, it’s hugely pleasing when you put together the pieces required to make progress.

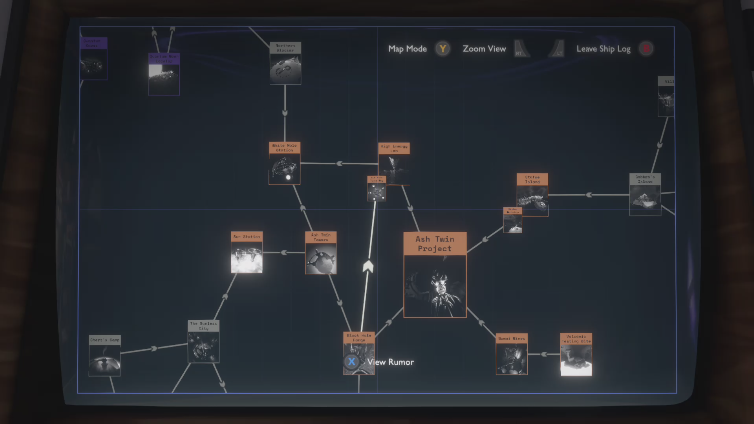

It is also worth talking about the fact that the game achieves this in part through use of a very compelling clue / information system. I don’t really play detective or detective-style games so maybe this is more common these days than I think, but this was the first game I’d played which had this sort of system in it. As you proceed through the game world (and through the various cycles) your ship-board computer fills out a grid or map of clues, which tell you what information you’ve already found, what that information connects to, and also alerts you when there might be “More to find” in a given area – this final point in particular is a really nice way of making sure people don’t think they’re exhausted the clues in a region and never return, all without knowing there was in fact some other potentially vital piece of information hiding there. In turn the grid then helps you piece together the various components and to remember some of the subtle pieces of information you’ve been given. The clue system strikes a wonderful balance because it never simply tells you where you should go or what you should do when you’re there – it just gives you the pieces and lets you figure that out – but it also never omits anything important or vital, and everything you need to complete the game can absolutely be found within it. Towards the end of the game once most of the clues have been exhausted, it also serves very nicely to gently and implicitly push you towards the areas you should look more at, or the ideas / themes you should focus on in your thinking, in order to uncover whatever remains to be found.

In essence: what The Witness was trying to do to fix the major design problems of old “adventure” games (but in doing so left me rather cold), The Outer Wilds was also trying to do and, for me at least, succeeded spectacularly. There are never any goofy puzzles where you have to read the designer’s mind and figure out, a la a game like Toonstruck, that you should put some jumping beans inside a cat toy, use glue to attach piano keys as teeth, and then deploy it outside a tree to seduce a randy squirrel. Who thinks of such things?! Instead the game gradually and cleverly builds up your knowledge of the world, your knowledge of the systems of the world, and what you learn on one planet or in one area can often apply quite nicely on another. In turn one of the most impressive pieces of design here is that all the different areas connect to each other in so many ways – and yet also stand on their own and can at least be somewhat explored without going anywhere else first – that you genuinely get a sense the worlds and their mysteries can be uncovered in pretty much any order. I, for instance, went to the twin planets closest to the sun last, which talking with some friends suggests is somewhere people often go first; while other puzzles I got through almost immediately while others apparently struggled on those. It’s a rare piece of design that gives you this much freedom and yet the game doesn’t collapse when you go to an area intended to be “early game” in the late game instead. You need to find everything, but there are so many paths through that “everything” that no two players are likely to get everything in the same sequence.

Now, of course, it was not perfect (as no work of art ever is). There was one (non-essential) puzzle hidden so extraordinarily well that in the end I had to read a very vague online hint to point me in the right direction, and after that I was able to track it down. Another puzzle elsewhere made me unsure whether I was supposed to wait for something to happen, to take some action, or whether I was totally misunderstanding it, and I think a little more clarity could have helped; but most interesting was a particular puzzle, I think one of the “latest” of the bunch (as in, one of the puzzles meant to be solved last). It turned into a source of frustration because I solved the puzzle, or thought I had, but didn’t get any outcome. As it turned out my solution was actually correct yet I had “attempted” it just ever-so-slightly incorrectly, but because I thought I had tried it I then immediately moved onto other possibilities, and tried and frustratingly exhausted a dozen other possibilities before I gave up, looked up the answer online – and found to my horror that I had guessed correctly the first time around! But that without knowing I had fractionally mis-performed the solution, and thus had incorrectly decided the solution was incorrect. I don’t think there is necessarily much that can be done about this, but it did strike me as an interesting case. This is one of those things which can only really happen in games, and only in games like this where the solutions are very “qualitative” in nature – it’s not to do with moving object X onto tile Y, but rather to do with these far more unique solutions to particular situations within the game world. Nevertheless, this is a rare and niche occurrence and one that would be difficult to prevent for all players; it didn’t detract in the least from my enjoyment of a stunningly original and deeply engrossing game.

I also played the expansion (I think it is far more of an “expansion” than a “DLC”) called Echoes of the Eye. The game’s developers went to significant lengths to actually keep the nature and content of this expansion a secret, and I can see why – although it keeps the basic puzzle-solving mechanics from the first game (pretty much all puzzles are unique and qualitative in nature, you collect clues, you piece them together and learn new things in order to progress, but you never gain new abilities, etc) the tone and setting are extremely different. It’s still set within the same universe and context but has a far more ominous and eerie tone, a few areas that are strange and otherworldly, and a few quasi-jump-scares as well. EOTE took me a little bit longer to get into than the base game but by the end I thought it was absolutely fantastic, using so many new clever puzzle ideas and so many surprising ways to hide things in plain sight, and the conclusion of the story was actually very moving. I did not, however, appreciate the “stealth” sections in this expansion which felt less like stealth and more like memorization sections – once I shifted my thinking to the latter perspectives I got through them easily, but I think presenting them as stealth sections will have frustrated a lot of people. The clue-coding computer, although still useful, was also a little less useful this time around – there was definitely some information that I considered vital which the computer just didn’t record, and when I was trying to navigate through the three stealth sections, the computer could have been a lot more useful. Nevertheless the developers get huge credit for making such bold and ambitious changes – most of which pay off – and the expansion is a tremendous addition to an already amazing game. I generally find it hard to find a puzzle game I truly enjoy but The Outer Wilds (and EOTE) were exactly this, and I treasured my time with them – an absolute joy from start to finish.

2021 -> 2022

So there we go! Another year of some excellent gaming experiences. Did you play any of these – and if so, what did you think? I do hope you all enjoyed these little micro-reviews, and I’ll be back with a new blog post on game dev stuff in the hopefully near future. Take care everyone!

A good friend spent some time showing me Bioshock Infinite. Interestingly, he was also nonplussed by the combat, but we both thought it might have been due to his general disinterest in FPS mechanics; clearly that’s not the case here, yet the game gave you the same impression. And it does rely on fake choices for storytelling rather a lot, doesn’t it?

Interesting! Yeah, it just seemed very flat and ordinary, and not just by modern standards; the combat in something like GoldenEye 007 or Perfect Dark feels way richer and fresher and more dynamic to be than what BI had to offer. And, heh, I didn’t get far enough to get a sense of that, but that’s interesting if so!

Thanks for the interesting games writeup. I too enjoyed playing The Curious Expedition with its bonkers mashup of swashbuckling, exploration, and the supernatural. I’d never heard of Hellpoint but your description of it sounds amazing, so I’ll definitely pick it up at some point. I got Control from one of the weekly Epic Games store giveaways and have been meaning to try it. Speaking of bizarre megastructures, have you ever read the manga ‘Blame’? It’s set entirely within an unfathomably gigantic megastructure that has long since fallen into ruin, and the manga has very little dialog. I think you may enjoy it. And I’ll check out your paper on the subject later too.

(I’ve only played a few minutes of Outer Wilds, so I deliberately skipped the last part of this writeup!)

Thanks crowbar! Yeah, TCE was such a highlight, but it was such a strong year with Outer Wilds and Hellpoint also in the running – this was a much harder one to decide on a winner for than the year before, that’s for sure. I have not read “Blame” but you have immediately intrigued me with this “unfathomably gigantic megastructure that has long since fallen into ruin” – that is my kind of setting! I will absolutely look into it 🙂

“Matter” by Iain M. Banks is another great book of this fun micro-genre!

(The “unfathomably gigantic megastructure” hasn’t entirely fallen into ruin tho!)

Hey Kenny, yes, agreed! It’s not one of my favourite Iain’s (it always felt like he just wanted to write a sort of medieval potboiler but felt obliged to put it in the Culture setting?) but the megastructures in general in the Culture-verse I really love. Fascinating stuff.